| Thanks to Debatenstein of Twitter for my new logo, "Side-eye Jane Austen"! This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws some occasional shade at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. |

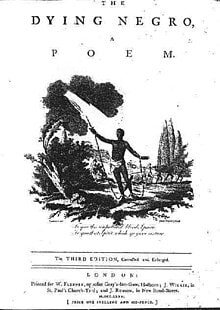

| In my last two posts, I reviewed a forgotten 1812 novel about a Black man living in Georgian England. British novelists, poets, and playwrights played an important role in the long struggle to end slavery. No-one living in the United Kingdom in the late 18th century could pretend not to notice the poems, novels, plays and essays which portrayed the cruelty and horror of the slave trade. Dramatic poems like “The Dying Negro” were intended to awaken the consciences and appeal to the emotions of British readers. A poem for children, written in the cadences of the Old Testament, associated the consolations of religion with the fight against slavery:

|

However, Georgian playwright Frederick Reynolds took a different approach—he used the vehicle of comedy, not tragedy, to stress the humanity of people of colour...

Abusive to Zebby, her servant

Abusive to Zebby, her servant Reynold’s play Laugh When You Can debuted at the Covent Garden Theatre in December 1799. A comic farce with a complicated plot involving marital misunderstandings, a thwarted seducer and a love-struck spinster, it enjoyed great popularity and was performed well into the 19th century.

The main plot of Laugh When You Can has to do with Mr. Delville, a man-about-town who plots to seduce the lovely Mrs. Mortimer while her husband is out of the country. He lures her to an inn but she refuses to cheat on her husband. Delville threatens to have his way with her. She is rescued by the light-hearted Mr. Gossamer, who was alerted to her plight by Mr. Delville’s servant.

The clever servant who outwits his master was a familiar stock character in theatre—not just in England, but all around the world and as far back as ancient Greece. But Reynolds added a twist to the familiar story.

The servant’s name is Sambo and he is a black man. Despite his stereotypical slave name, Sambo defies the typical caricatures of the times. Black characters in books and plays often spoke using a crude dialect and referred to themselves in the third person, as we saw with the novel Yamboo. The slave Zebby in the novel The Barbadoes Girl (1816) is abused by her spoiled young mistress, but speaks up in her defense: “Sir, me hopes you will have much pity on Missy, she was spoily all her life, by poor massa, and when Missy pinch Zebby, and pricky with pin, massa say only – poo! poo! she be child! naughty tricks wear off in time.” In Elizabeth Helme’s Modern Times (1814) another spoiled girl orders her slave Juba to wade into the ocean to retrieve her riding crop before it drifts away. He balks: “Me fear, missy, something matter. Dog no go—he always please with water.” Juba is ordered into the surf where he is bitten in half by a “sea monster.”

Isabella Mattocks

Isabella Mattocks In marked contrast, Sambo in Laugh When You Can speaks the King’s English, the same as the other characters. Historian John A. Hodgson points out that Sambo is “virtuous, well-educated, well-spoken, and thoughtful.”

Sambo carries himself confidently and intercedes in the other character's lives several times. He scornfully turns down a bribe to falsely testify that Mrs. Mortimer has been unfaithful to her husband. Because he has read his employer’s law books, he saves Mr. Delville from being arrested for debt. He recounts: “there was a flaw in the indictment—they arrested him in the wrong county!... The writ was made out into Middlesex; and we, being the other side of the bridge, were in Surry, you know!—so we snapp’d our fingers, and defied them!”

Reynolds uses Sambo as a device to criticize English society. He scolds Mr. Delville with: “the natives of my country are all very healthy, and for two simple reasons—first, because we’ve no doctors, and next because we’ve no such enlighten’d disorders as ingratitude, false friendship, seduction!” He tells Mrs. Mortimer she shouldn’t have allowed Mr. Delville to get her alone: “Begging your pardon ma’am, in your own thoughtlessness – don’t be angry – but the world judges by appearances.”

Reynolds tailored the parts in his play to the comic abilities of the Covent Garden regulars. Isabella Mattocks had been a member of the troupe for over thirty years. She was cast as Miss Gloomly, a writer of sentimental novels. When Dorothy, her flattering maid, describes her novels as “moral and entertaining,” Miss Gloomly angrily retorts: “Entertaining!—why the girl’s mad! –I never wrote anything entertaining in my life! No—all my works are calculated to excite sighs, and tears, and terror, and distress… in the thirty-six volumes I have published, I defy you to produce a single joke.” When another character jokes about challenging the troublemaking spinster to a duel, Sambo agrees: “Challenge her--shoot her and welcome.”

Actor John Fawcett originated the part of Sambo at Covent Garden. Fawcett looks rather dark-complected in this youthful portrait but other portraits make it clear he is a typical fair-skinned Englishman. During his career, however, he "blacked up" for many roles. Fawcett started his stage career playing the tragic role of Oronooko, an African prince sold into slavery, and he also undertook Othello. But according to the Dictionary of National Biography, Fawcett didn’t shine as a tragic actor and made the switch to comedy. Reynolds appears to have written the role of Sambo to play up Fawcett’s strengths, because the Dictionary says “in representations of bluff honesty and rude manly feeling [Fawcett] had no equal.” Accordingly, Reynolds gave Fawcett lines like: “as it is my duty to serve my master in a good cause, it is my duty to thwart him in a bad one.”

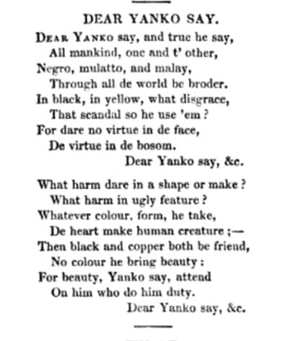

Fawcett was also known for his fine singing voice. Sambo repeatedly sings a comic song by Charles Dibdin, Dear Yanko Say, which declared (albeit in pidgin English) that all men are brothers and that virtue is not to be found in the face, but in the heart. The lyrics are below.

Black servant in livery

Black servant in livery As well, the specific directions for Sambo's costume ("a white jacket, silver shoulder knot, white waistcoat, glazed round hat, gold band, cockade, boots, and leather breeches"), indicate that he wore elaborate livery, playing into the stereotype that Black people prized finery.

Bluff and manly: John Fawcett out of blackface. British Museum

Bluff and manly: John Fawcett out of blackface. British Museum The play was better received in England. A reviewer writing in the Monthly Mirror (1798) understood that the portrayal of Sambo was something new on the stage: the “sentiments… put into the mouth” of Sambo “are calculated to prove that the negro is our fellow creature, with moral and intellectual faculties… like those of other men.” The reviewer added, “The tendency of this character must atone for some improbabilities annexed to it. It is certainly good to maintain that a difference of complexion should be considered as the only difference between the European and the African.”

To this reviewer, Reynold’s underlying message was clear: “Fawcett, in the [role of the] black, felt and spoke like a determined enemy to the Slave Trade.”

| West Indian Fortunes I should mention too, the sub-plot involving Mr. Gossamer and the girl he loves, because their marriage only comes about because she is a West Indian heiress and owns plantations. Mr. Gossamer tricks her uncle into thinking the plantation has been destroyed by a hurricane; thinking his niece is now a pauper, he quickly gives permission for her to marry, to have her off his hands. But her plantations are just fine and she gets her happy ending with Mr. Gossamer. Laugh When You Can was a popular success for its author, and it was performed around the country. Jane Austen might have seen the play while she was living in Bath. I think she would have laughed at the character of Miss Gloomly. The Black actor Ira Aldridge (1807-1867) (who also played Othello and King Lear) performed as Sambo at the Royal Coburg Theatre in London in a musical adaptation of the play. According to a history of the theatre in New York, Laugh When You Can “for half a century remained a favorite with actors and audiences.” |

| The song Dear Yanko was reproduced in the best-selling Elegant Extracts. If you can sight read or play, (alas, I cannot), the music for the song is here. For more examples of anti-slavery literature in Austen's time, check here and also here. There was of course, literature produced by anti-abolitionists, including cartoons ridiculing the abolition movement and depicting people of colour in stereotypical fashion. Timely West Indian fortunes were a frequently used plot device for many an 18th century novel and play. For more, click here. Hodgson, John A.. Richard Potter: America's First Black Celebrity. University of Virginia Press, 2018. Ireland, Joseph Norton. Records of the New York stage, from 1750 to 1860. 1866. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed