| This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws some occasional shade at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. This post is about a forgotten four-volume novel, and is part of an exploration of portrayals of merchants from Bristol and their families in novels of this period. I'm interested in this topic because of Mrs. Elton. |

Tanya Reynolds in the 2020 Emma

Tanya Reynolds in the 2020 Emma That brings us to the 1802 novel Nobility Run Mad: I decided to plow through all four volumes, not because I was interested in another story about the nobility behaving badly, (they usually behave badly), but because this book came up in a search for novels of this era that featured the words “Bristol” and “merchant.” I wanted to see if this novel, like some others I’ve read, portray Bristol merchants as being vulgar.

| Bristol Merchant as a Comic Scrooge: Backstory I The first Bristol merchant we encounter in Nobility Run Mad is a Mr. Samuel Filmore, a successful but small-minded and miserly importer and exporter. In the opening chapters of the novel, we hear Mr. Filmore’s backstory related by a neighbour. Filmore’s parents were humble labourers. Sam was able to go to a charity-school and at sixteen he got a job as a clerk. In time, he married his employer’s widow, and after she died, he made another advantageous marriage. He acquired enough of a fortune so that his daughter Betsy attracted the attention of a young nobleman. Star-struck, Filmore handed over a dowry of £140,000. He didn't know the Marquis had already gambled away his own patrimony, as well as his first wife’s dowry. Betsy's riches disappeared the same way, at the gaming tables, to Filmore's lasting chagrin. We might admire Mr. Filmore for his climb from rags to riches in a highly stratified society and the fact that he doesn't gamble away his fortune, but no, he’s a comic villain. Not because he is tangentially involved in the slave trade, but because he is of low origin; he is tight-fisted, close-minded, and uncouth. And --bonus sneer points: he’s a Methodist. Being a Methodist in this instance means that he relies on faith to get him to heaven and not good works, and therefore he needn’t trouble himself about the poor. (For more about how Methodists were portrayed in novels of this era, see here.) Thus we have a novel, written at the same time as other novelists were writing abolitionist novels, which editorializes about a great many things:

| Samuel Filmore "was, from nine years old to sixteen, a Blue-coat-boy in that excellent school, founded by that most charitable of men, the late Mr. Coulston, of generous memory.” This is a reference to Edward Colston, now infamous as a slave-trader, whose statue was recently tipped into Bristol harbour. (Staffordshire figure of a "Colston Boy Bristol") |

References to hogsheads of sugar, to trading ships arriving in harbour--this is presented in a matter-of-fact manner. The praise of the philanthropic Mr. “Coulston,” i.e. Edward Colston, the biggest slave trader in Bristol, tells us that opinions have changed since 1802. Further, the author of this book conjures up vast fortunes as needed for her plot from the East and West Indies. Two characters in the book acquire their riches in East India. Mr. Filmore marries a West Indian heiress. His son-in-law spends his wife's West Indian inheritance at the gaming table. His grandson marries a West Indian heiress. And by "West Indian heiress" I don't mean a woman of color like Miss Lambe in Sanditon. The only reference to a person of color in the novel is a joking reference to a soap advertisement showing a man trying to scrub a "blackamoor" white.

Other novels of this same period, some of them from the same publisher, were written from an abolitionist point of view. It goes to show that opinions varied on this subject, from support to indifference to outrage, but you could still be an accepted member of society at this time and view slavery as a fact of life and use a West Indian fortune as a plot device, not as a political statement.

After all the opening exposition, in which fortunes are acquired and lost and wives and useless noblemen die, we have a wealthy gentleman named Milner who is planning a long trip to the continent for his health. He hears about Mr. Filmore’s grandson, the orphaned offspring of Betty and the dissolute nobleman. This grandson, also called Samuel Filmore, has an older half-brother by his father's first marriage. Despite the fact that young Samuel is rightfully Lord Samuel, a member of the nobility, he's been ignored by his paternal grandfather and brought up in Filmore's counting house. Our wealthy stranger, out of pity for Samuel, takes him along to France so he can acquire the kind of cosmopolitan polish he'll need if he ever wants to fit in with his late father’s relatives.

Though published in 1802, the story is set in the year 17---, that is, some vague year before the French Revolution. France is chock-a-block with aristocrats and the Bastille is a notorious prison but there is no political foreshadowing in this novel. Instead, we have a lot of dialogue from the loquacious young Samuel. You can take the young man out of Bristol, but it’s going to be uphill work taking the Bristol vulgarity out of the young man. He is selfish, self-satisfied, and parochial in his outlook. He has no interest in art or culture, and he’d rather save a guinea than spend it.

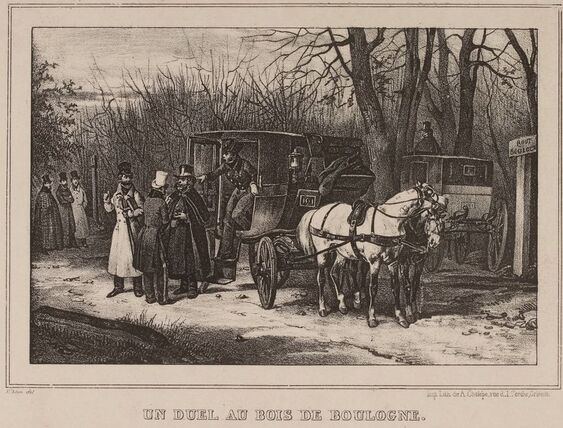

Milner and Samuel are staying at an Inn in Saint-Omer on the way to Paris. Looking out the window, Sam admires an exceedingly handsome carriage with an entourage of horses and servants. Samuel admires the coat of arms on the carriage. They apply to a servant for information and Sam learns that the traveler is his own noble half-brother, Gustavus Osmond, the Marquis of Raymond. But he doesn't get a chance to meet him. (Ahem, Janeites, does this remind you of anything?)

Lord Raymond's first wife was “the widow of a Jew merchant, whom report made out to be worth a million.” In the first iteration of the story, this sounds pretty callous but later, Lord Raymond tell his own story which softens the details. The widow fell in love with him. The marriage was a transactional one but he had affection for her. The marriage gave him, at 19, independence from his grandfather the duke so he was free to do what he was longing to do--pay all of his late father's debts so he could restore the family honor. After his first wife died (and nothing unusual about that, wives drop like flies in this book for the convenience of the plot), he married again. Arpasia Ermington was a beautiful girl of good family but she was unfaithful to him so he divorced her. He fought a duel with his wife’s seducer, survived his injuries, but has been in poor health ever since, mostly because of the shock and heartache of the faithless Arpasia’s betrayal. HIs only pleasure in life is in doing good for others.

For example, during his brief stay in Saint-Omer, the Marquis learned of an Englishman and his wife who have been imprisoned for debt. He generously pays off their debts in full and gives an additional sum to help the stranded couple.

Samuel thinks his noble brother was naïve:

| “I think I know how to make a good bargain better than the Marquis. I am rather more up to things of this kind; so in my Lord’s place, why I would have sent for all these here French creditors, and when I had got them all together—‘Now, gentlemen,’ says I, (always give such low traders a little palaver when one wants to make a good bargain—it is granddad’s maxim, and a very good one) ‘now gentlemen, what is your demand,’ says I, ‘upon my countryman?’ They all tell me, of course—‘Well then,’ says I laying a good round sum upon the table before me, just to set their mouths a watering, ‘there,’ says I, ‘lays the money as you see. Now what are you willing to take?...I will give you half the sum he owes you, if you will all give a proper receipt for the whole; and if you won’t comply with my terms, why he must starve in prison; that’s all I have got to say, for depend upon it, you will never have so generous an offer again. A prison never pays debts, you know: so I should think, gentlemen, if I was in your places, that half a loaf is better than no bread, and I ain’t obliged, you know, to give you a single sixpence…" etc. etc |

headless gothic squirrel in Germany

headless gothic squirrel in Germany Mr. Milner and Samuel make the acquaintance of Lord Raymond in Paris and the young nobleman kindly acknowledges Samuel as his brother, despite Samuel's unprepossessing personality. The section set in Paris is taken up with Lord Raymond’s re-encounter with his faithless wife Arpasia, now the kept mistress of the army captain who seduced her. Everyone—Lord Raymond, her parents, her brother Lord Bewdly—are absolutely gutted by this turn of events.

Arpasia's father refuses to forgive her. And she turns down the suggestion that she enter a convent to atone for her sins. “I must be either happy, miserable, virtuous, or wicked, my own way.” We see her at her salon, playing the harp or bedecked with jewels in a box at the opera.

The Marquis resolves to try to forget her and move on. He joins forces with his uncouth half-brother and Mr. Milner (who turns out to be an old friend of his late father, who has reformed from gambling), and they journey together to the healthful climes of southern France.

They pause in the city of Dijon in Burgundy and rent a castle, which leads us into a gothic interlude. Or rather a gothic satire, because only young Samuel is affected by the rumors of ghosts and hauntings while Lord Raymond and Mr. Milner laugh at him. He is frightened by strange rustlings and movements in his bedroom, but it's only the housekeeper's pet squirrel. He listens to scary stories of a loup-garou (a French werewolf) prowling the castle at night. He decides to go out and kill it, and ends up shooting a goat.

It’s interesting the author chooses to make fun of gothic tropes, à la Northanger Abbey, because her publisher, Minerva Press, was a leading purveyor of blood-chilling gothic tales. Some academics have theorized that the reason the first publisher who bought Northanger Abbey held it back from publication was because it spoofed gothic novels which were very popular and he didn't want to give offense to the readers or writers of gothic novels. Here we have an example that you could have your gothic cake and spoof it, too.

So far, apart from the dissolute off-stage antics of Samuel's late father in the backstory, we haven't had any nobility running mad. We do get more Bristol merchants, though. Walking around Dijon, Sam is surprised to encounter Mr. Middleham, another small-minded Bristol merchant, with his family. “He is a soap-boiler and tallow-chandler, and in a devil of a line—exports and imports by wholesale,” Samuel explains. In other words, he renders animal fat to make soap and candles, a smelly and undignified trade. He's got people to do the boiling for him, of course. Even in 1802 you have the rise of factories and the mass manufacture of commercial items, the earliest glimmers of the industrial revolution.

Bristol was home to some large soap-making factories, or "soap works." Is "Mr. Middleham" a satire of a real soap and candle magnate? In the book, he's dishonest, miserly, coarse and vulgar. If that weren't bad enough, he's also a Methodist. | Despite their wealth, the Middlehams live very frugally. While abroad, they stay in cheap lodgings. Mr. Middleham and Samuel’s grandfather had long planned to join Middleham’s ward Theodosia (known as Dousy) and Samuel in matrimony. There is yet another great fortune at play here, since Mrs. Middleham, who spends all her time quarreling with her husband, is the widow of “a great West India planter” and Theodosia is her step-daughter and heir to her late father's fortune. I presume Mrs. Middleham is specified as being a step-mother, not a mother, to explain how such a fat, ignorant, common, woman could be mother to such a lovely, accomplished girl. This is a book that sets a lot of store by bloodlines. Theodosia "cordially despises" them both and is just waiting until she's 21 and can get away from them. Samuel is complacent at best about the idea of marrying Theodosia. He does not put himself out to win her affections. Theodosia has been to boarding school and she can play and sing and draw and paint. Samuel says he is “no judge" of her talents but "I had rather my wife should know how to make a good pudding or a pie.” Lord Raymond graciously invites the Middlehams to the castle for tea, despite their vulgarity and bickering, and so he and we meet Theodosia. Lord Raymond is instantly taken with her accomplishments, good sense, and beauty, and he pities her for having to put up with the Middlehams. Hmm, so here we have a rich, handsome, high-born guy finding himself attracted to a young lady with vulgar relatives. |

Elizabeth Johnson by Reynolds

Elizabeth Johnson by Reynolds Will Lord Raymond die of his wasting illness before he can find love and happiness again with the girl intended for his brother? Will Lord Raymond's grandfather, the Duke, succeed in promoting a match with a haughty noblewoman whom our hero doesn't love? Will the fascinating but fallen Arpasia survive to the end of the novel, or will she be paid out for her transgressions? And do Samuel’s manners ever improve? Next post....

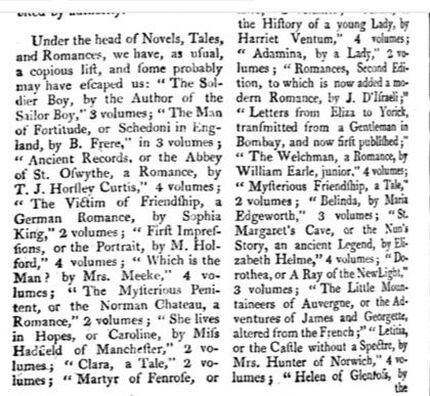

| The Anonymous Authoress We don't know who wrote Nobility Run Mad, except that she's also the author of The Sailor Boy (1800) and The Soldier Boy (1801). She is not Rosalia St. Clair, (real name Agnes C. Scott) a Scottish novelist who also wrote novels titled The Sailor Boy and The Soldier Boy three decades later. Our authoress identified herself as the "author of" as Jane Austen did, (see opposite) but did not add "by a lady." As we see in the listing of novels opposite, some female authors gave their names, such as "Miss Hadfield of Manchester." Sometimes you can't tell if the writer is a man or a woman as in "T.J. Hortley Curtis," some were "by a Lady," some mention no authorship at all, just the title. Notice the publication of First Impressions, or the Portrait, which of course was Austen's first name for the novel that came out as Pride and Prejudice. |

The Bristol Heiress and A Winter in London also vulgar feature Bristol merchants.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed