| And what are you reading, Miss—?” “Oh! It is only a novel!” replies the young lady, while she lays down her book with affected indifference, or momentary shame. “It is only Cecilia, or Camilla, or Belinda”; or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language. -- from Jane Austen's defense of the novel in Northanger Abbey |

Abelard & Heloise

Abelard & Heloise A 1799 book review in The Quarterly Review explains the biggest concern -- impressionable young people are so caught up in sentimental romance, that real life seems tame in comparison: “those romantic visions which throw into a dead gloom the brightest scenes of real life. And yet, “real life is the very thing which novels affect to imitate; and the young and inexperienced will sometimes be too ready to conceive that the picture is true, in those respects at least in which they wish it to be so. Hence both their temper, conduct and happiness may be materially injured."

Real life, even real love, and the realities of married life, are nothing like a sentimental novel. The Quarterly Review warns that novels teach susceptible young ladies to believe that “no sacrifice can be too great for real love; that real love such as subsists, and ever will subsist, between herself and the best of men, is adequate to fill every hour of her existence, and to supply the want of every other gratification, and every other employment.”

The 1796 play, The Generous Attachment, takes on the dangerous romance issue and also touches on the concern that fictional suffering in novels made women indifferent to real suffering.

In the opening scene, Mr. Mortimer interrupts his wife while she is reading (and presumably weeping) over a Gothic novel. She complains: “here have you now, by your boisterous intrusion, disturbed my mind from the delightful tract of sensibility it was thrown into, from musing over the distresses of the charming Emily in that exquisite production of female genius The Mysteries of Udolpho.”

“I wish, Mrs. Mortimer,” he answers, “you would extend your feelings of sensibility to living objects as well as fancied woes, and imaginary distresses.”

She retorts: “ideas are floating on my imagination, and I am building castles in the air with the man I could love, with a total forgetfulness of the man I am married to... and from the regions of delight to which I was ascending, [you] bring me down to a level with the inhabitants of this world, and only to consider myself as plain Mrs. Mortimer."

“And if you were only to consider yourself as plain Mrs. Mortimer, my dear, I believe no one who knows you, would accuse your consideration of telling a falsity.”

This satire was a little too heavy-handed even for Georgian audiences, because I can find no record that this play (which was published at the author's expense), was ever performed.

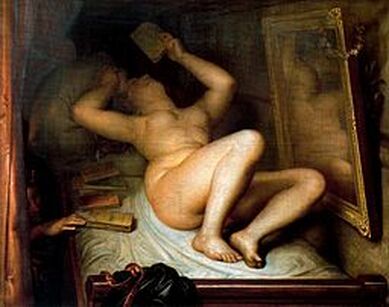

The Reader of Novels by Antoine Wiertz c 1853

The Reader of Novels by Antoine Wiertz c 1853 Her book Instructive Rambles extended, in London and the adjacent villages (1811) is not a novel but it contains short fictional anecdotes including the sad tale of a poverty-stricken widow who lays the beginning of her downfall to the fact that she read too many novels when young. Her mother had the habit, so she followed her parent's example:

After being widowed, the mother "retired into the country; and naturally of a pensive disposition, her only amusement was reading; and a wish, perhaps, to banish unpleasant thoughts, led her to the perusal of books which, though they might sometimes beguile an uneasy hour, were undoubtedly unfit for me to be suffered to indulge in; which was frequently the case.

"From reading these, as I grew up, I formed fallacious opinions of human nature; and too ignorant and unacquainted with life to draw a middle line, my inflated imagination presented my fellow creatures as either perfect beings or monsters of deformity. Romances had represented some characters as perfectly happy; and resolved to be so myself…”

The foolish girl enters into marriage but: “Alas! I was disappointed; the shadow again beguiled me; my husband possessed neither religion, good-humour, nor humanity. Charmed with his fine person, I had never considered further… He was also a gamester…”

The same author wrote in her novel Modern Times (1814) about a spoilt young girl whose “education had been erroneous in the extreme… she had been indulged in an indiscriminate perusal of novels, and her ideas had kept pace with this species of literature.” As a result, she is susceptible to flirtation: “Her head was stored with lovers—honorable and dishonorable, the mere distinction of which, to a young, giddy and vain girl, like Fanny Neville, appeared immaterial…”

In her novel Albert, or the Wilds of Strathnarvon (1799), the young heroine Gertrude falls a victim to this hyper-romanticism and secretly pledges her love to her brother's tutor, who only wants her money. Gertrude's aunt laments: “her brain was heated, and her mind empoisoned with the romantic pursuits she was continually imbibing.”

Austen agrees that what we read affects our character and our mood: in Persuasion, heroine Anne Elliot recommends that Captain Benwick read more inspiring memoirs and moral essays and less romantic poetry: "she thought it was the misfortune of poetry to be seldom safely enjoyed by those who enjoyed it completely; and that the strong feelings which alone could estimate it truly were the very feelings which ought to taste it but sparingly."

Update: My book club is reading The Way We Live Now (1875), by Anthony Trollope, and here, decades later in the high Victorian age, we have the same trope. A girl of humble birth, Ruby Ruggles, who falls under the spell of romantic novels and imagines that the handsome baronet wants to marry her, not just seduce her: "This was a realisation of those delights of life of which she had read in the thrice-thumbed old novels which she had gotten from the little circulating library at Bungay." Another heroine in the book, Marie Melmotte, also thinks she's in love with the baronet: "she had learned from novels that it would be right that she should be in love, and she had chosen Sir Felix as her idol."

Spinsters, or old maids, were fair game for comedy in Georgian England

Spinsters, or old maids, were fair game for comedy in Georgian England “Sir Edward was surprised; he had perhaps little expected to meet with so spirited an opposition to his will. 'Where, Edward in the name of wonder (said he) did you pick up this unmeaning gibberish? You have been studying Novels I suspect.' I scorned to answer: it would have been beneath my dignity. I mounted my Horse and followed by my faithful William set forth for my Aunts.”

Austen's not the only one who had a good laugh at sentimental novels. in the 1799 play Laugh When You Can, one of the comic characters is Miss Gloomly, a prolific writer or dramatic works. MIss Gloomly scolds a young man to "leave off grinning and smiling."

"Excuse me," he answers, 'it’s impossible."

"Impossible!" she exclaims. "Read my works, and then see if it’s impossible."

Miss Gloomly wants to marry Mr. Mortimer, but, as her maid Dorothy says, “Mr. Mortimer won’t hear of a divorce [from his wife].”

"Brute! idiot!" the scorned Miss Gloomly responds. "And did he send no message, Dorothy?"

"None, madam," answers Dorothy, "and when I asked him if this was treatment for the author of Artemisia, the Victim of Sensibility, and The Confusions of the Soul--"

"Effusions, girl!" snaps MIss Gloomly. "How often must I correct you? Effusions of the Soul, besides, elegies, sonnets, and other pathetic and moral publications."

Camilla, the titular heroine of Fanny Burney's popular novel, was only 17. Camilla was one of the works Austen named in Northanger Abbey as a "work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language." But then, Charlotte Heywood does not reject Camilla on the grounds of its merits as literature, she rejects it because she can't relate to the heroine.

Charlotte's verdict on Camilla is one of several hints that Austen intended to include a satirical treatment of sentimental novels in Sanditon. However, the person whose brain is overheated by them is not a female, but a man. In the fragment, Austen introduces the character of Sir Edward Denham, who aspired to be a dangerous seducer, based on novels like Clarissa. Sadly, we'll never know what Austen would have done with this theme or how she would have handled it differently from her satirical parody of Gothic novels in Northanger Abbey.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed