| “Here is another one for you, Price: causa latet, vis est notissima— ‘the cause is hidden, but the result is well known’. You are learning Latin, you told me, to converse with your brother officers, but perhaps there is another reason—perhaps, you wish to impress a certain uncle, who is father to a certain young lady…..” William Price grinned. “It’s like that fellow you told me about—that fellow who wrote War in Disguise. He knew that people can have more than one motive for doing a thing.” “Mr. Stephen. Yes. Clever fox—he saw that Parliament could not be persuaded to outlaw the trade in slaves for moral reasons. So, he made the French slave trade a casus belli, if you will-- “A casus bell-eye?” “Look it up in your grammar, Mr. Price." -- Fanny's brother trying to get a classical education in A Contrary Wind |

Mrs. Leyster rescues a destitute widow

Mrs. Leyster rescues a destitute widow In The Two Cousins (1798), the benevolent Mrs. Leyster takes in a destitute widow and her baby. Mrs. Leyster’s young daughter Constance asks if she can help raise and educate Jenny, the little baby.

“But tell me, my child,” [asks Mrs. Leyster] “What do you intend to teach her?”

“I will teach her, mama, as soon as she can learn, to read, to spell, and to [do needle]work, afterwards she shall learn to write, and I will instruct her in drawing and dancing.”

“Very well,” said Mrs. Leyster, “then I suppose you will finish by giving her a good fortune."

When little Constance, surprised, protests that she can't do that, her mother explains that the sort of education Constance proposes will render Jenny unfit for the station in life in which Providence placed her...

Mrs. Leyster calibrates Jenny’s future position in the social hierarchy with exactitude: she will not “be reduced to the condition of a lower servant,” so it’s all right if she learns to read, write, do sums and learn plain needlework. “And she shall be instructed by Martha in confectionary and pastry. I will also have her know how to assist in cooking, in cleaning fine linen, and even doing the less laborious work of the house…”

Fatherless Fanny is denied an education

Fatherless Fanny is denied an education In the best-selling Fatherless Fanny, a little girl is left at a boarding school with no information about her relatives and a note for 200 pounds. After the money runs out, the headmistress stops her music and drawing lessons and threatens to send her to the workhouse. Of course her true parentage is revealed in the end.

The same question confronts Mrs. Barnet in Edward: Various views of human nature, taken from life and manners, chiefly in England (1798). She sends clever young Edward to the local grammar school, but what should he be trained for? Mr. Barnet’s friend Mr. Temple tricks Mr. Barnet into sending Edward to study law by urging against it: “The world [will] laugh at the folly of giving a boy an education that would fit him for one of the learned professions, when you intend to breed him a tradesman… I hope at least you will not think of the law… because the world would blame you very much.”

“The world may go and be d----d,” answers Mr. Barnet. “Am I to mind its fancies?” He impulsively resolves that Edward “shall be sent to one of the best schools in England, there to learn as much Latin as I please…ay, and Greek too if I think proper, and you may make my compliments to the World.”

The dilemma faced by the Barnets is not so different from Sir Thomas Bertram’s caution in respect of his niece Fanny Price. “There will be some difficulty in our way… as to the distinction proper to be made between the girls as they grow up: how to preserve in the minds of my daughters the consciousness of what they are, without making them think too lowly of their cousin; and how, without depressing her spirits too far, to make her remember that she is not a Miss Bertram." Once she has a genteel education, Fanny will not be able to return to her old life--as indeed she discovers. Like Mrs. Leyster, Sir Thomas believes that if he educates Fanny to be a gentlewoman, he is morally obliged to "secure to [her] ... the provision of a gentlewoman."

Gentlewoman visiting a village charity school

Gentlewoman visiting a village charity school The novels and conduct books of the day include cautionary tales about parents of the lower or middling classes who gave their children an education--and therefore expectations--which made them dissatisfied with their station in life.

In The Young Woman's Guide to Virtue, Economy, and Happiness (1817), John Armstrong opines that: "those belonging to the lower orders of middling life" should avoid the "high and polished branches of education, which are utterly inconsistent with the circumstances of their families. This error... has become very general, and is productive of much human misery."

In I’ll Consider Of It! (1812), Major Farringdon thinks Mrs. Clarkson should remember that she is merely the daughter of a soldier, although she has won the lottery. Therefore, she should not over-educate her daughter. “Pardon me, the world, especially the great world, will still remember your former situation, and many will even think, that Miss Clarkson is already too accomplished for a young lady of her fortune.”

“But I have very great views for my daughter;” Mrs. Clarkson protests, “these I shall at present keep entirely to myself, and a governess she certainly must have…”

Fanny Belton’s father, a poor curate, gives her a classical education in The Woman of Letters (1783). After he dies, she saves a few of “the best Greek and Latin authors” from his library while the rest is sold off. Her father’s friend writes: “I pray to heaven her turn for literature may be of use to her—but I fear the contrary. My wife… a plain good woman, often says, she wishes Fanny had been bred to her needle rather than to her pen, as by the former, she might have been enabled to have acquired a genteel livelihood.”

In contrast, some girls escape this fate in Coraly (1819). The heroine admires the demeanor of some village girls attending a village fête hosted by the local baronet. He agrees: “Those neat and good girls were great favourites of my aunt’s, and she taught them several useful things herself. How much more respectable they look in those neat brown gowns, and pretty little caps, than some of the others, whose mistaken parents have ruined their happiness, corrupted their taste, and made them discontented, by putting them to what is called a lady’s school.”

Even Mary Wollstonecraft, in her Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1788), warns parents of modest means to guard against "going on in thoughtless extravagance, and anxious only that their daughters may be genteelly educated... consider to what sorrows they expose them.”

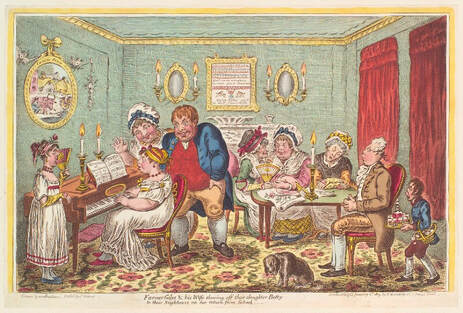

| The narrative switches to first person as the girl says “I thought myself not without beauty; heard from my governess and teachers that the way to be accomplished was to read French, play music, dance, and sing Italian airs… When I returned from school, I found, alas! my accomplishments… were of no use in helping to my mother to serve in the shop. "Tom Chink, the pewterer, used to tell me I was a likely lass, and actually made his addresses to me. My parents told me I could not do better, for that Tom was a thriving man. No, no, said I, if you had intended me for a tradesman you should not have made me a BOARDING-SCHOOL YOUNG LADY. I never read, in any novel, of any of the heroines throwing themselves away upon a mechanic.” | 'Farmer Giles and his wife shewing off their daughter Betty to their neighbours, on her return from school' by James Gillray, published by Hannah Humphrey, hand-coloured etching, 1809, National Portrait Gallery |

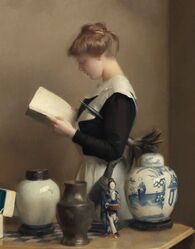

The House Maid, William McGregor Paxton

The House Maid, William McGregor Paxton Over-education, as we have seen, was thought to be a bad idea for working-class girls. It was also seen as weakening society as a whole.

The narrator in The Advantages of Education warns: “Suppose for one instant that the rage for idleness (I beg pardon, I mean refinement; I always mistake those words) should spread to the next order in society, and our housemaids and cooks, weary of their dirty occupations, should grow as refined as their young ladies. The industrious mother cannot perform all the domestic affairs herself, and as we do not live in Utopia, but in a country, where exertion must precede enjoyment, our elegant girls must either be useful or starve."

As we've seen, Sir Thomas understood that if he took his niece Fanny into his household, he would be changing her life forever because he would be changing her social class.

"Sir Thomas himself was... proud of his niece; and without attributing all her personal beauty, as Mrs. Norris seemed to do, to her transplantation to Mansfield, he was pleased with himself for having supplied everything else: education and manners she owed to him."

As Mansfield Park ends, the same favour will be conferred upon Fanny's younger sister Susan. In my guest blog at Austen Authors, I ask, but why did Austen put Susan into the novel?

Previous post: Men do not want silly wives Next post: Learning to manage a household

| Education, Literacy and the Reading Public, by Amy J. Lloyd, Gale Primary Sources (pdf) Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. The opinions are mine, but I don't claim originality. Much has been written about Austen. Click here for the first in the series. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed