Examples of 18th century poetry and prose about Cupid and flames

|

“[A]nd the cleverness of this trifle [ie the Kitty riddle] is shown in its throwing guessers off the scent by sending them to explore the region of fades,* common-places about love, and flames and cupids.”

— Percy Hetherington Fitzgerald, biographer of David Garrick, 1867 (*a lesser-known definition of "fade": an adjective meaning insipid or commonplace; see Merriam-Webster)

See also: Authorship and Variations of Kitty, a Fair But Frozen Maid. The complete Kitty poem is posted there as well. |

My article about the meaning and significance of the riddle Kitty, a Fair but Frozen Maid in the novel Emma appears in the December 2022 online version of the Jane Austen Society of North America journal Persuasions. While millions of readers have enjoyed Austen's novel Emma, they may not be aware that modern scholars regard this riddle, partly quoted in the novel, as being worse than bawdy--experts tell us that it is obscene, coarse and horrific, because it speaks of "willing victims" who bleed. This riddle has been interpreted as being about the "flames" of venereal disease and it allegedly references cures which were used at the time--namely, treating the sufferer with mercury smoke fumes and deflowering virgins.

Jane Austen dropping a reference to venereal disease and deflowering virgins in Emma? Mr. Woodhouse trying to recall an obscene riddle to recite to Harriet and Emma? Yes, that is what modern academics believe and this is what they teach.

My article rebuts this interpretation, but I won't repeat my entire argument here. Instead, I'm posting examples of 18th century love poetry to provide additional evidence that the idioms and imagery of Kitty, a Fair but Frozen Maid, far from being disturbing or perverse, were indeed commonplace in love poetry, both serious and comical, of the 18th century. Further, many of these idioms are still used today in song lyrics.

Jane Austen dropping a reference to venereal disease and deflowering virgins in Emma? Mr. Woodhouse trying to recall an obscene riddle to recite to Harriet and Emma? Yes, that is what modern academics believe and this is what they teach.

My article rebuts this interpretation, but I won't repeat my entire argument here. Instead, I'm posting examples of 18th century love poetry to provide additional evidence that the idioms and imagery of Kitty, a Fair but Frozen Maid, far from being disturbing or perverse, were indeed commonplace in love poetry, both serious and comical, of the 18th century. Further, many of these idioms are still used today in song lyrics.

|

Austen’s favorite moral writer, Dr. Johnson, included a comical love letter in a letter-writing manual that he edited.

Here the writer jokes about the intensity of his flame of love:[ii] Madam… that son of a Whore Cupid has pink’d me all over with his confounded Arrows, that, by my troth, I look like… your Ladyship’s Pincushion… For, Madam, while I was Star-gazing t’other Night at your Window, full of Fire and Flame (as we Lovers use to be) I dropt plumb into your fish-pond, by the same Token, that I hissed like a red-hot Horse-shoe flung into a Smith’s trough. ‘Twas a hundred pound to a Penny, but I had been drowned, for those that came to my Assistance, left me to shift for myself, while they scrambled for boiled Fish that were as plenty as Herrings at Rotterdam.

|

|

|

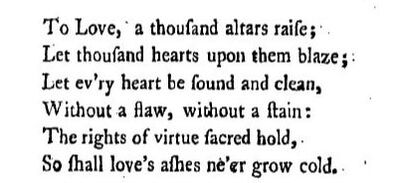

Love’s fire could be purifying, like a refiner’s fire.

|

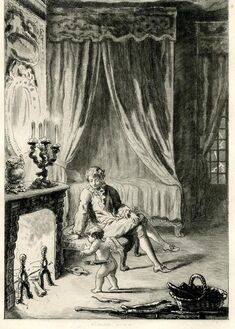

Figurine of Cupid disguised as a physician

|

|

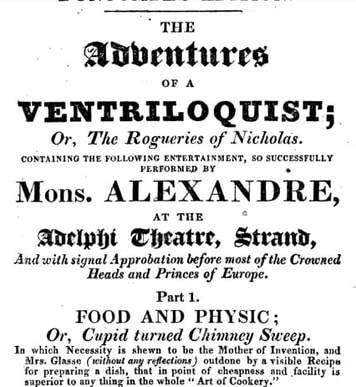

In the 1807 poem Felix and Eugenius,[iii] Eugenius is surprised to see his old friend Felix, who he thought drank himself to death. Felix explains that he was saved by the love of a good woman: Eugenius is skeptical that love could have wrought such a miracle. Felix insists: You never felt of love those sacred fires That wake chaste hopes and delicate desires… |

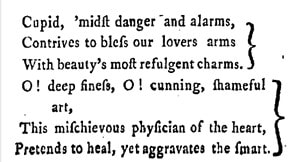

Eugenius exclaims that Cupid is usually thought of as a prankster, but here, he is a doctor who has saved Felix from his “disease,” which is not venereal disease, but his vice of alcoholism.

Cupid, methought, in pranks like these display’d His busy, meddling, mischief-making trade… A prodigy of kindness shows to thee In him a friend indeed in need we see; Quack-like (at least in all but handling fees) He cures thee of incurable disease… |

|

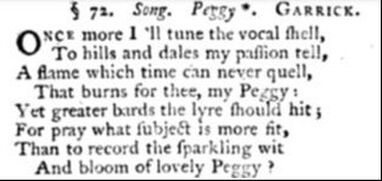

Garrick's Flame of Love

|

|

In the 1811 novel Metropolis, a cynical duchess argues the advantage of marrying for money, not love, and again, "flame" clearly refers to passion, not to venereal disease: “Cupid is represented blind, and Hymen [the god of marriage] in full possession of his eyesight; for lovers see only perfections; the illusion vanishes, and the deception becomes more cutting. I have had experience, and in spite of the whole tribe of poverty-struck novel writers, give me what they emphatically term a Smithfield bargain. Talk of flames, darts, and wounded hearts? What are they, to the delicious sounds of settlement, pin-money, jointure, title, town and country establishments? These are enjoyments which never pall…”

|

|

Cruel Cupid

In a 1783 poem published in The Lady’s Magazine,[iv] or Entertaining companion for the fair sex, Cupid’s darts are “peace-destroying,” he is “cruel” and the “bane of joy.” The poet pleads, “Thy dart withdraw from out my breast:”

Victims and Bleeding

The Kitty stanza which sounds the most shocking to modern ears refers to "willing victims" who "bleed." This sounds violent to us, but again, it was a common-place idiom in 18th century love poetry.

|

(Above) "Love Arrow" refers to something rather more naughty here.

Below, "Love is Just Like War," with Joan Blondell |

Alice Chandler asserted the line: “some willing victim bleeds” is “literally hymeneal” (39). “Hymeneal” is a reference to Hymen, the god of marriage. Some 18th century poets, notably Pope, referred to married people as the victims of Hymen, as in his 1711 epistle to a female friend: But, Madam, if the Fates withstand, and you / Are destin’d Hymen’s willing victim…[ix] The poets. casting back to classical poetry of the Romans, spoke of love's votaries as victims sacrificed on the altar of love to the goddess Venus. The Kitty riddle uses the fireplace as doubling for the altar.

|

An 1800 poem by a “Mrs. Hale” has Chloe regretting her marriage:[x]

O no, never fear, he’s so formal, so cold, I never, no never, can love him again; Why then, cruel Hymen, two victims withhold, When both would rejoice to get rid of thy chain? Her friend Hebe answers: Yet tell me, my Chloe, pray can it be so-- Did Cupid himself your two hearts then unite? By Love himself kindled, no torrent could flow I thought could extinguish a flame once so bright. Chloe refers to Cupid as “the boy,” just as in the Kitty riddle: My dear girl, let experience persuade Believe not what men when they’re lovers will say; For no sooner the boy saw the fools he had made, Than he blew out his torch, and strait flew far away. The Forlorn Lover, 1750 To find my wounded bleeding heart, You’d know it by the golding dart. If you, by fortune find it there, Conduct it home to me with care. And you shall well rewarded be, For such like fidelity. Perhaps you may it behold Among the lambs in Cupid’s fold, Confined like a captive slave, If so, the boon of Cupid crave., etc. Of course, writers used the phrase "bleeding victim" to refer to warfare, to Jesus on the cross, and in other contexts, but unarguably, they also used it to being a victim of love at the hands of Cupid's dart:

Forbear, fond God, forbear your Dart, Seek not to wound a Dying Heart At Chloe's Feet it gasping lies, A bleeding Victim to Her Conqu'ring Eyes -- Song, 1713, by H. Clements |

From Acontius to Cydippe, a 1808 translation of Ovid, we find more “bleeding victims” of love:

…As Cupid’s arrows have been felt by me, Beware lest Phoebe’s should be aim’d at thee… But when—-so heav’n permit—the signals sound, And bleeding victims stain the sacred ground: A golden image of the fruit be seen, With these two verses to the quiver’d Queen…[xi] Aphra Behn, an early female writer and playwright, composed this song, with "dying" as a sly reference to sexual climax: Time and Place you see conspire With tender Wishes fierce desire; See the willing victim stands To be offer’d by your hands; Ah! Let me on Love’s Altars lying, Clasp my Goddess whilst I’m dying. A tribute to a half-a-dozen (probably real) young ladies at a horse fair includes a stanza to a maiden named Syer which includes the full classical panoply of darts, wounding, Venus, and bleeding victims.

Syer next advances with becoming grace.

Gaze not, ye youths! On that bewitching face. Death surely strikes us from that piercing eye, And Darts unnumber’d with those glances fly. See, see, ye gods, and from your heav’n admire That heaving breast, which gives the world desire. Oh! See that heavenly form, that shape, that air, And then confess another Venus there. Swains without number round the fair one wait, And fall, like bleeding victims, at her feet. But ah! Her favour they pursue in vain; She hears their sighs, but won’t regard their pain; Now with a smile their wishes seems to crown, Now knits her brow, and kills ‘em with a frown… "Verses upon the Ladies at the Horse Race on Babergh-Heath in Waldingfield, Suffolk."

September 1736, anonymous, The London Magazine and Monthly Chronologer. |

Tainted Love -- once I ran to you,

now I run from you Love lies bleeding in my hand...

I wonder if those changes have left a scar on you Like all the burnin' hoops of fire that you and I passed through |

|

I've found one example of "bleeding victims" that refers to Hymen. In this poem, which seems to combine a tribute to Rousseau with some gossip concerning the lives of the nobility, playwright and classical scholar Richard Jodrell laments the practice of forcing girls into marriage. They are victims and slaves, forced to perjure themselves at the altar. Mercenary marriage, says the poet, is like prostitution.

The Rocks of Meillerie, an epistle from the C---n---ss of D---b---y to the D---ke of D---r---t.

by Richard Paul Jodrell, 1780.

Georgian Cupid chimneypiece detail Georgian Cupid chimneypiece detail

Cupid clichés

These idioms were so widely used that they were regarded as clichés. In The Ladies Polite Songster, 1780, a girl complains about the overwrought clichés her suitor uses: Young Colin seeks my heart to move, And sighs and talks so much of love, He’ll hang or drown I fear for it; Of pangs and wounds and pointed darts, Of Cupid’s bow and bleeding hearts, I vow I cannot bear it.

Another poet decides to forgo the clichés in his 1762 poem A Familiar Letter of Rhymes to a Lady: [xii]

…Therefore, omitting flames and darts, Wounds, sighs and tears, and bleeding hearts, Obeying, what I here declare, Makes half my happiness, the fair…. The favourite subject I pursue, And write, as who would not, for you…. |

From The Picture, a 1766 novel, love as a human sacrifice (above) and Cupid as a physician (below). The sacrifice at the altar is related to the virtue and purity of the lovers' hearts. These poems are contemporaneous with the Kitty riddle which also uses a fireplace as a substitute for the altar in its imagery.

|

Joseph Addison printed a parody of a love-letter in issue #71 of The Spectator in 1797, supposedly written by an uneducated footman. This garbling of clichés was seen as comic:

My Dear Betty, Remember your bleeding lover, who lies bleeding at the wounds Cupid made with the arrows he borrowed at the eyes of Venus, which is your sweet person… “Poor James!” said the editor, who offers to re-write the letter: “the style of which seems to be confused with scraps he had got in hearing and reading what he did not understand.”[xiii] (Left, Cupid with a torch and a flower) |

|

Cupid and Fireplaces

There's another Cupid/fireplace connection which I gather would have been known to the well-educated Georgian Englishman. An ode by the Greek poet Anacreon tells of a man who finds Cupid shivering with cold on his doorstep. He invites him in to warm himself by the fire. But once the urchin recovers, he fires a dart at the poet's heart, and flies away. The blog "Gods and Foolish Grandeur" displays a series of paintings illustrating the poem, with an 1800 English translation of the Ode. The print at right shows shows a contemporary interpretation of the tale. Click here for an earlier 1713 translation of the third ode of Anacreon. |

Figures of Cupid and Psyche or Cupid and Venus were popular subjects for "chimney-pieces," that is, decorations on the mantelpiece or front of a chimney.

In the early 17th-century Beaumont and Fletcher Jacobean Tragedy, Cupid’s Revenge, Cupid’s priest is told that the king has banned the worship of Cupid: “I must deface your Temple, though unwilling, and your God Cupid here must make a Scare-crow for any thing I know, or at the best, Adorn a Chimney-piece.” In the wildly popular 1802 novel Thaddeus of Warsaw, we find another association of Cupids with chimney-sweeps, again in reference to unrequited love, and not venereal disease. In this passage, two young ladies are distressed that the handsome Mr. Constantine (in fact a Polish nobleman in disguise) has been clapped into Newgate prison for debt. A society fop, Mr. Lascelles, enjoys teasing them: "Determining to gratify his spleen, if he could not satisfy his curiosity, this witless coxcomb continued the whole day in Harley Street, for the mere pleasure of tormenting Euphemia [Dundas]. From the dinner hour until twelve at night, neither his drowsy fancy nor wakeful malice could find one other weapon of assault than the stale jokes of mysterious chambers, lovers incognito, or the silly addition of two Cupid-struck sweeps popping down the chimney to pay their addresses to the fair friends." In 1813, Jane Austen visited a boarding school in London and mentioned "some naked Cupids over the Mantlepeice" in the school's drawing-room in a letter to her sister Cassandra. |

|

|

Final thoughts

|

"Cupid Disguised as a Chimney Sweep," Meissen, mid-eighteenth century, one of a set of 92 Cupids

"Cupid Disguised as a Chimney Sweep," Meissen, mid-eighteenth century, one of a set of 92 Cupids

[i], “To Sally at the _____Chophouse,” The Lady's Monthly Museum, (95).

[ii] Johnson, Samuel. A compleat introduction to the Art of Writing Letters, (163).

[iii] Jones, Jenkin. “Eugenius and Felix,” Pros and cons, for Cupid and Hymen (128—138).

[iv] “Cupid Triumphant, or Damon in Chains,” in The Lady's Magazine. (48).

[v] Nicol, Alexander. Nature without Art: (66).

[vi] “Annelide and Arcite,” in Charlotte, an Elegy, etc. (15).

[vii] Anonymous, “Written by a young lady,” Edinburgh Magazine, 119.

[ix] “Epistle to Miss Blount,” in The Works of Alexander Pope. (398).

[x] “Dialogue,” in Poetical attempts. By Mrs. Hale, 1800, (102).

[xi] James, Charles. “Acontius to Cydippe.” Poems. T. Egerton, 1808., (89).

[xii] Lloyd, Robert. “A Familiar Letter of Rhimes to a Lady,” The St. James's Magazine for December 1762. (228).

[xiii] Steele, Richard., Addison, Joseph. “To Elizabeth,” in The Spectator #71, May 22, 1778. (87).

[ii] Johnson, Samuel. A compleat introduction to the Art of Writing Letters, (163).

[iii] Jones, Jenkin. “Eugenius and Felix,” Pros and cons, for Cupid and Hymen (128—138).

[iv] “Cupid Triumphant, or Damon in Chains,” in The Lady's Magazine. (48).

[v] Nicol, Alexander. Nature without Art: (66).

[vi] “Annelide and Arcite,” in Charlotte, an Elegy, etc. (15).

[vii] Anonymous, “Written by a young lady,” Edinburgh Magazine, 119.

[ix] “Epistle to Miss Blount,” in The Works of Alexander Pope. (398).

[x] “Dialogue,” in Poetical attempts. By Mrs. Hale, 1800, (102).

[xi] James, Charles. “Acontius to Cydippe.” Poems. T. Egerton, 1808., (89).

[xii] Lloyd, Robert. “A Familiar Letter of Rhimes to a Lady,” The St. James's Magazine for December 1762. (228).

[xiii] Steele, Richard., Addison, Joseph. “To Elizabeth,” in The Spectator #71, May 22, 1778. (87).