Percy Bysshe Shelley

1792 - 1822

Percy Bysshe Shelley

1792 - 1822

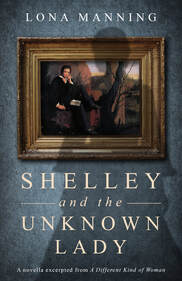

Percy Bysshe Shelley: background for my novel A Different Kind of Woman

In A Different Kind of Woman, I have faithfully represented Percy Bysshe Shelley’s activities and travels in the years 1818/1819, except for the detail of meeting Mary Crawford Bertram. My story is inspired by a tantalizing mystery in Shelley's life, the story of the mysterious lady.

Shelley did read and sunbathe naked in the forest outside of Bagni Di Lucca. He spent a few days there by himself before he returned to bring Mary Shelley and Claire Clairmont from Livorno. He went on a solo horseback trip to Lucca, leaving Mary at home, but he also went horse-riding with her in the mountains. Claire hurt her knee. His books were held up by an Italian customs-office and delivered to him four months later. An English valet was stabbed.

Shelley took Claire to Venice and his manservant Paoli Foggi helped make the travel arrangements. And Mary Shelley swiftly left town in response to Shelley’s summons, and their baby daughter died.

After travelling around most of the autumn, the Shelleys settled in Naples in December 1818. Again, Shelley rushed ahead and arrived in Naples before his wife did, just as he had done in Bagni di Luccca.

In Naples Mary and Shelley were both feeling very depressed. They did a lot of sightseeing, however. Claire Clairmont was ill and saw a doctor on December 27th.

A baby named Elena Adelaide Shelley was registered with the Neapolitan authorities on the evening of February 27 and the Shelleys left Naples the next morning, leaving the baby behind. Sadly, her death was reported a year and a half later.

Much of Shelley’s dialogue in this story is taken from his letters, and from novels in which Shelley appears, thinly disguised, as a character. His widow Mary put Shelley-like men into her novels, Likewise, Disraeli put characters based on Byron and Shelley in his novel Venetia and Shelley’s friend Thomas Peacock lovingly satirised Shelley in his “crotchet” novels Headlong Hall and Nightmare Abbey. The poetry quoted is all Shelley’s, except for when he first meets Mary in the forests above Bagni di Lucca; then he quotes from his friend Peacock’s poem Rhododaphne.

In A Different Kind of Woman, I have faithfully represented Percy Bysshe Shelley’s activities and travels in the years 1818/1819, except for the detail of meeting Mary Crawford Bertram. My story is inspired by a tantalizing mystery in Shelley's life, the story of the mysterious lady.

Shelley did read and sunbathe naked in the forest outside of Bagni Di Lucca. He spent a few days there by himself before he returned to bring Mary Shelley and Claire Clairmont from Livorno. He went on a solo horseback trip to Lucca, leaving Mary at home, but he also went horse-riding with her in the mountains. Claire hurt her knee. His books were held up by an Italian customs-office and delivered to him four months later. An English valet was stabbed.

Shelley took Claire to Venice and his manservant Paoli Foggi helped make the travel arrangements. And Mary Shelley swiftly left town in response to Shelley’s summons, and their baby daughter died.

After travelling around most of the autumn, the Shelleys settled in Naples in December 1818. Again, Shelley rushed ahead and arrived in Naples before his wife did, just as he had done in Bagni di Luccca.

In Naples Mary and Shelley were both feeling very depressed. They did a lot of sightseeing, however. Claire Clairmont was ill and saw a doctor on December 27th.

A baby named Elena Adelaide Shelley was registered with the Neapolitan authorities on the evening of February 27 and the Shelleys left Naples the next morning, leaving the baby behind. Sadly, her death was reported a year and a half later.

Much of Shelley’s dialogue in this story is taken from his letters, and from novels in which Shelley appears, thinly disguised, as a character. His widow Mary put Shelley-like men into her novels, Likewise, Disraeli put characters based on Byron and Shelley in his novel Venetia and Shelley’s friend Thomas Peacock lovingly satirised Shelley in his “crotchet” novels Headlong Hall and Nightmare Abbey. The poetry quoted is all Shelley’s, except for when he first meets Mary in the forests above Bagni di Lucca; then he quotes from his friend Peacock’s poem Rhododaphne.

|

Sources for dialogue in A Different Kind of Woman

The only Fannys I have ever known were exceedingly sweet-tempered. Shelley is thinking of Fanny Wollstonecraft Godwin, Mary Godwin’s oldest daughter, who committed suicide. Mr. Godwin believed it was because she was hopelessly in love with Shelley.

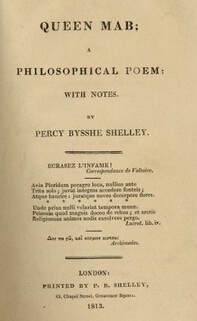

the partner of my life should be one who can feel poetry and understand philosophy. This is how Shelley excused his abandonment of Harriet, who was pregnant with his second child, in a letter to his friend Peacock. brutish, stupid, ignorant Italians – yes, Shelley was very insulting about all foreigners, Italians, Germans, French and Swiss and disparaged other countries such as Japan and China and India. You are my Luxima—did you ever read The Missionary? The Missionary: an Indian tale (1811) was one of Shelley’s favourite novels. Laon and Cythna was revised and republished under the name The Revolt of Islam I am careless of the consequences as they affect me, I only bitterly lament the depravity and mistake of those who persecute. As to me, I can but die, I can be torn to pieces...” this is adapted from a letter Shelley wrote to Lord Byron It is no reproach to me that Mary no longer fills my heart with an all-sufficing passion, In fact, this is what Shelley wrote to his first wife Harriet, “It is no reproach to me that you have never filled my heart with an all-sufficing passion,” when he informed her of his love for Mary Godwin. Think of the future ages which will come after you and I are mouldering in the dust! This phrase is adapted from a letter Shelley wrote to William Godwin: “[I will] make myself the cause of an effect which will take places ages after I have mouldered in the dust.” She does not understand me – Shortly before his death, Shelley wrote to a friend that Mary did not understand him. Yes, the old “my wife doesn’t understand me” line. he is completely a part of nature, as though he shares the same spirit with the trees and the sky. Claire would describe Shelley in this way in her old age. We have only to wait for [Shelley’s] father to die, and that will not be much longer. In fact, Timothy Shelley lived to the advanced age of 90. Shelley’s only surviving son, Percy Florence Shelley, inherited the baronetcy in 1844 when he was 25. Comfort at least by your pity a heart torn by your indifference—lend me some aid to endure the trial you have brought upon me…” this plea is from the novel Lady Singleton, written by Shelley’s friend Thomas Medwin, and is a fictionalized version of Shelley’s encounter with a mysterious lady. Surely our mutual situations compel us to disregard all considerations but that of the happiness of each other – similar to an explanation Shelley wrote to his friend Thomas Peacock, explaining why he had left Harriet for Mary Godwin. “If your whole soul does not urge you to forgive me—if your entire heart does not open wide to admit me to its very centre—forsake me, never speak to me again" —spoken by Raymond to Perdita in Mary Shelley’s novel, The Last Man. indeed, my pecuniary condition is a very painful one, Shelley used this phrase in a letter to his friend Leigh Hunt. The descriptions of Italy on the trip from Este to Naples are taken from Shelley's letters to his friend Thomas Peacock. In Naples “He looked as he had always looked, wild, intellectual, unearthly, like a spirit that had just descended from the sky” is from the memoirs of his friend Thomas Jefferson Hogg. "That is nothing more or less than what the world says of me..." Shelley did not deny that he had an affair with his wife's step-sister Claire. He wrote this in a letter to his wife. Indeed, you are never deterred or discouraged in schemes for my advancement and well-being—this sarcastic response is adapted from a letter Shelley wrote in November 1812 to Fanny Imlay. Her stepfather, William Godwin, had been giving Shelley unwanted advice. I had expected more of greatness and generosity from you.. Shelley actually wrote this to his first wife, Harriet, after he abandoned her. The most sacred considerations require me to conceal the details of my delicate situation from Mary – Shelley used those words in a letter to William Godwin about the pickle he had landed in that winter in Naples, but he did not confess the details. She is connected to one of the noblest families in the land – Shelley is describing a mysterious lady who he says pursued him. For more, see Shelley and the Mysterious Lady. |

Claire Clairmont

Claire Clairmont (also known as Jane or Clare or Clara Clairmont) was a clever and passionate girl whose long life was shadowed by her impetuous decision to run away with Shelley and Mary when she was fifteen. She was the daughter of William Godwin's second wife and although she was Mary Shelley's sister, they were not blood kin. Nobody seems to know who her father was. Update: her father has been discovered. Claire worked as a governess in Europe and Russia and she received offers of marriage, but she never married. Some of her journals have survived, but unfortunately the pages have been destroyed for all the truly interesting episodes. William Godwin

Mary Shelley’s father, William Godwin was a prominent figure in the late 1700’s, an influential writer whose book, Political Justice, deeply influenced Shelley. For a deeper dive, click here.

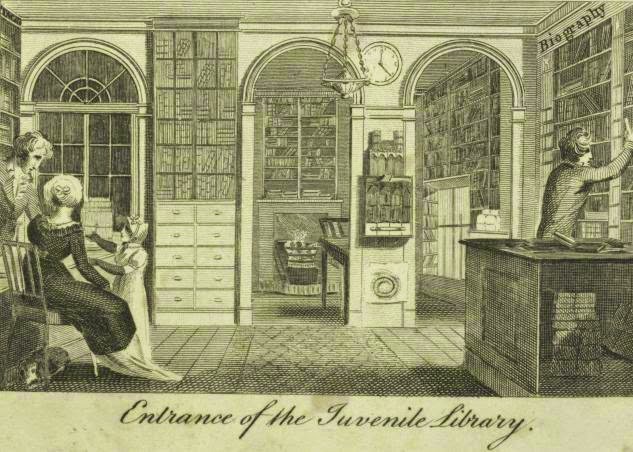

By the early 1800’s, his star had dimmed, he was chronically short of money and he sent begging letters to Shelley and Mary in Italy. Godwin’s second wife, Mary’s stepmother, set up a bookstore specializing in children’s literature. This shop was called the ‘Juvenile Library.’ Godwin wrote historical books for young people under pseudonyms like “Theophilus Marcliffe” and he commissioned his friends Charles and Mary Lamb to write Tales from Shakespeare which became a classic of juvenile literature and is still in print today. I discuss another one of their publications in this blog post, and there's more about the second Mrs. Godwin. Charles Lamb worked as a clerk at the East India Company headquarters. I wanted to work that into the novel but didn't have space or time! Mad Mary Lamb by Susan Tyler Hitchcock is an interesting biography of the Lambs and their literary circle in London.

Mr. and Mrs. Gisborne

The Robinsons in A Different Kind of Woman were real people. Their real names were Mr. and Mrs. Gisborne.

I changed their name to Robinson because we already had a Gibson and a Godwin in this book. Too many "G"'s! Maria Gisborne was a friend of the Godwin family when William Godwin was married to Mary Wollstonecraft. A young widow herself, she helped take care of little Mary after her mother Mary Wollstonecraft died. Godwin proposed to her but she turned him down. She later married Mr. Gisborne. The Gisbornes lived in Livorno, Italy where they befriended Percy and Mary Shelley. |

Memorial for Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Shelley at Christchurch Priory, Christchurch.

Picture by Androom (01 Jul 2017)

Memorial for Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Shelley at Christchurch Priory, Christchurch.

Picture by Androom (01 Jul 2017)

Shelley's legacy

Shelley drowned in 1822. Mary Shelley devoted the years of her widowhood to burnishing her late husband's reputation. “I am still his,” she wrote in her journal, “still the chosen one of that blessed spirit—still vowed to him forever and ever!”

Death obliterated all of Percy Shelley's faults in his widow's eyes, and she only remembered his virtues and his talents. She was devastated to learn their old friends thought she had been unkind to him.

Her son and daughter-in-law did a lot to create the Shelley "brand," Shelley as an ethereal spirit, too pure for this earth. On the other hand, Thomas Corddry Jeaffreson’s downright snarky 1885 biography broke with the hagiographies, and points out that Shelley told a lot of falsehoods and was ruthless about discarding people he fell out with.

Claire Clairmont outlived Shelley and Mary by decades. She never married. In her youth, she threw herself at Byron, who soon tired of her. In her old age, she left a unfinished memoir expressing her anger at both Byron and Shelley for leading themselves and the women they cared for down the path of free love, which led to such miserable and tragic consequences. This scrap of writing was discovered by biographer Daisy Hay.

Shelley’s ideas for the organization of society and government and his propensity for communal household living were a hundred years ahead of his time. He would have been completely at home in a hippie commune. He would have been the one strumming a guitar and getting high while somebody else washed the dishes.

His cousin Thomas Medwin wrote of Shelley: “How painfully interesting is his Life! With so many weaknesses—with so much to pardon—so much to pity—so much to admire—so much to love...”

Shelley drowned in 1822. Mary Shelley devoted the years of her widowhood to burnishing her late husband's reputation. “I am still his,” she wrote in her journal, “still the chosen one of that blessed spirit—still vowed to him forever and ever!”

Death obliterated all of Percy Shelley's faults in his widow's eyes, and she only remembered his virtues and his talents. She was devastated to learn their old friends thought she had been unkind to him.

Her son and daughter-in-law did a lot to create the Shelley "brand," Shelley as an ethereal spirit, too pure for this earth. On the other hand, Thomas Corddry Jeaffreson’s downright snarky 1885 biography broke with the hagiographies, and points out that Shelley told a lot of falsehoods and was ruthless about discarding people he fell out with.

Claire Clairmont outlived Shelley and Mary by decades. She never married. In her youth, she threw herself at Byron, who soon tired of her. In her old age, she left a unfinished memoir expressing her anger at both Byron and Shelley for leading themselves and the women they cared for down the path of free love, which led to such miserable and tragic consequences. This scrap of writing was discovered by biographer Daisy Hay.

Shelley’s ideas for the organization of society and government and his propensity for communal household living were a hundred years ahead of his time. He would have been completely at home in a hippie commune. He would have been the one strumming a guitar and getting high while somebody else washed the dishes.

His cousin Thomas Medwin wrote of Shelley: “How painfully interesting is his Life! With so many weaknesses—with so much to pardon—so much to pity—so much to admire—so much to love...”

|

More Reading

A good short biography of Shelley by Luciano Mangiafico is available online here. For more about Shelley’s radical beliefs and the philosopher William Godwin who had a profound influence on him, there is Shelley, Godwin and Their Circle, by Henry Noel Brailsford (1873) which provides a very readable overview of their lives and times. Newman Ivey White’s 1947 two-volume biography of Shelley is also worthwhile. Paul Johnson has an interesting chapter about Shelley in his 1988 book, Intellectuals which really brings home his reckless, selfish behaviour. Contemporary books about the Shelleys and the Godwins which I'd recommend are: Shelley: The Pursuit, by Richard Holmes. Obviously I take a more jaded view of Shelley than does Mr. Holmes. He places more reliance on Shelley’s veracity than I do, but this is a thoroughly researched and well-written work. The Young Romantics, by Daisy Hay, a very enjoyable read which ties together the lives of the Shelleys with some of their contemporaries. I also recommend Godwins and the Shelleys: Biography of a Family, by William St. Clair, although there is more about Godwin and less about Shelley for some readers. |