"According to the account which Shelley gave to Byron and Medwin, he re-encountered in Naples the married lady who had proffered her love to him in 1816. She... informed him of the persistent though hopeless affection with which she had tracked his footsteps." -- A Memoir of Shelley, by William Michael Rossetti, (1886)

Photo credit: Wolfgang Moroder

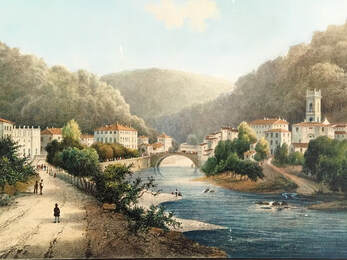

Photo credit: Wolfgang Moroder Something—nobody knows what exactly—happened in Naples in the winter of 1818 concerning Shelley and a baby girl. There is some question about how much of the whole story Mary Shelley ever knew, and she later suppressed the few details that were available.

During the winter of 1818/19 Shelley was living in Naples with his wife (Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein,) his wife's step-sister Claire, who was possibly pregnant, and a pregnant nursemaid. By the time he left Naples in February, he had taken financial responsibility for a new-born baby girl...

RSS Feed

RSS Feed