| Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. For some, recent interpretations of Austen appear to be part of a larger effort to jettison and disavow the past. Click here for the first in the series. |

The Enclosure movement part 3:

Gleaners look for stray grains of wheat, 1857. It's been a long time since the West experienced this kind of poverty

Gleaners look for stray grains of wheat, 1857. It's been a long time since the West experienced this kind of poverty So what did Jane Austen think? .....

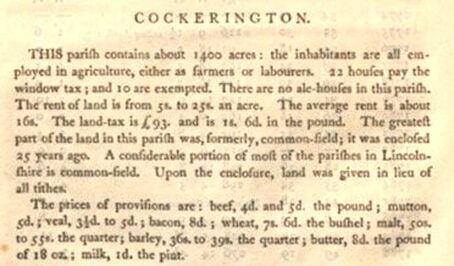

Excerpt from "The State of the Poor" by Sir Frederick Morton Eden, 1797 The clergyman of this parish received land instead of a yearly collection of tithe-produce.

Excerpt from "The State of the Poor" by Sir Frederick Morton Eden, 1797 The clergyman of this parish received land instead of a yearly collection of tithe-produce. Professor Celia Easton has carefully reviewed all of Austen's existing corpus for references to farming and enclosure. In an article for the Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA), Easton starts with the most explicit mention of enclosure, which is not in Emma, but in Sense & Sensibility. John Dashwood tells Elinor that he's enclosing Norland Common, and the cost of doing so is "a most serious drain" on his income. Later in the novel, the men talk about enclosure over their after-dinner drinks. Austen presents John Dashwood throughout the novel as a selfish and incredibly self-centred person, so his mention of enclosing Norland Common does sound like she disapproves of closing off the common land.

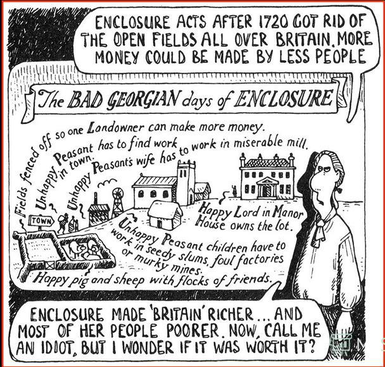

From a history page that is anti-enclosure, click on cartoon for more

From a history page that is anti-enclosure, click on cartoon for more However, I don't think there is any indication that Mr. Rushworth is planning to enclose more farmland; he intends to re-design his existing parkland. Henry Crawford's concerns about Thornton Lacey are strictly aesthetic as well. The farmyard Crawford wants to clear away appears to belong to the parsonage. It doesn't look like any villagers will be affected, which is the question at issue here.

Austen shows affection for Mr. Knightley's old-fashioned home with its unimproved landscaping: "the Abbey, with all the old neglect of prospect, had scarcely a sight—and its abundance of timber in rows and avenues, which neither fashion nor extravagance had rooted up." In fact, comparing Mr. Knightley's home to General Tilney's pride in his modernized Northanger Abbey, we see that Austen is gently mocking about this new-fangled landscaping movement. Both John Dashwood and General Tilney have greenhouses -- and they are both bad guys in Austen. Dashwood and Rushworth have cut down or intend to cut down the old trees which line their avenues. The focus here is on showy landscaping, not enclosure.

(Interesting side note, some of those expansive Capability Brown-landscaped meadows were more than ornamental, they were profitable because sheep could safely graze serenely on them, and the landowner could make money selling wool and mutton. This is the part where people who know what a "ha-ha" is can nod knowingly. Ah yes, the ha-ha.)

Many of Austen's characters enjoy walking outside and enjoying nature -- Fanny Price in particular -- so there is nothing reprehensible about enjoying a beautiful landscape. Perhaps it is all a question of moderation. As Fanny says of Mrs. Grant's shrubbery: "There is such a quiet simplicity in the plan of the walk! Not too much attempted!”

In Persuasion, Anne Elliot joins in a very long ramble across fields divided by fences and hedges. Anne enjoys the melancholy beauty of autumn, and meditates on how the farmer and his plow attest to the promise of spring, but is there even a hint that the enclosed land she's walking through, the hedgerow she's resting beside, are symbols of the cruel disenfranchisement of the peasants?

And what about Emma, the book that is Exhibit "A" in Dr. Helena Kelly's contention that Austen was anti-enclosure? In the JASNA article, Dr. Easton points out that Emma Woodhouse pays a charitable visit to a poor family, a family that could well have been affected by the loss of common grazing rights, but Easton does not single out any passages in Emma that refer to land enclosure. She evidently does not see the "politicized references" that Dr. Helena Kelly sees in mentions of hedges.

Old-fashioned tithes

Old-fashioned tithes Simon J. White writes in Romanticism and the Rural Community: “There is little evidence within [Austen's] novels that Jane Austen was radically opposed to enclosure in particular or agrarian reform in general. Indeed, as Robert Clark and Gerry Dutton have found, Austen’s father was ‘as engaged in capitalist agricultural activity as any farmer would be today’."

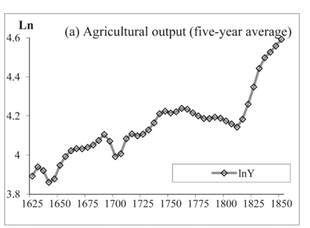

Podcaster Ellen points out in Reading Jane Austen (Season 3, episode 5 at 39:35) that the rise of agricultural output more acre meant more income for the clergy because the value of their tithe, or money in lieu of tithes, increased. Enclosure and the agricultural revolution made clerical livings more appealing to a higher class of the gentry.

In Northanger Abbey, Henry Tilney has his own "young plantations" (that is, areas that are newly planted or forested) and he concentrates on improving their value as he looks forward to his marriage. Edmund Bertram and Edward Ferrars are also shown as being interested in getting as much value as they can out of the lands (called "glebe lands") they control in the parish. Edmund is learning from Dr. Grant "how to turn a good income into a better" and Edward and Elinor would like "rather better pasturage for their cows." As well, they are intent on making their little parsonage look grander by adding shrubberies and a big curved driveway (a sweep). Professor Easton points out "The fact that clergymen have a particular interest in land enclosure is evident in Jane Austen’s fiction..."

Emma talks to Harriet of what the poor must suffer in winter. But she doesn't add, "If only that vile Mr. Knightley hadn't forbidden them from gathering firewood from the forest!" Dr. Kelly sees subtle criticism; I think the subtleties she sees are in fact non-existent, particularly in Emma.

Which brings us to the final question -- would it have been risky for Austen to protest against land enclosure? Well, that would depend on how far she had gone in her opposition, or what she had proposed as a solution. Since land enclosure was pretty much a done deal, I think you could safely and publicly lament the hardships imposed upon the common folk, without demanding that the land under cultivation be returned to common use. Nothing is easier than condemning public policies carried out twenty, thirty, fifty, years ago and usually you will win applause for doing so.

Ang, James B., et al. “Innovation and Productivity Advances in British Agriculture: 1620–1850.” Southern Economic Journal, vol. 80, no. 1, 2013, pp. 162–186. JSTOR

Ang, James B., et al. “Innovation and Productivity Advances in British Agriculture: 1620–1850.” Southern Economic Journal, vol. 80, no. 1, 2013, pp. 162–186. JSTOR Another radical writer, Thomas Spence, thought all land should be kept in common. But he also wanted an end to the aristocracy. He went to prison. Likewise, William Cobbett, a writer and MP, opposed land enclosure. He went to prison, but over other issues, not land enclosure.

Oliver Goldsmith's 1770 poem, The Deserted Village, mentions a proud nobleman who grabs land to create an artificial lake and extend his parkland, but Goldsmith wasn't locked up for writing it and the poem was popular and frequently reprinted. Goldsmith's poem is a nostalgic lament for a vanished rural village, a way of life that was gone forever. It was not so political as to get Goldsmith into trouble.

The fact is that land enclosure ended up benefitting everyone in time, as we can see from the chart above which shows the dramatic rise in agricultural output resulting from the agricultural and industrial revolutions. And as this article points out, it's easy to romanticize that abandoned rural village. The reality is that rural life was monotonous when it wasn't precarious.

According to Professor Easton, "Jane Austen never explicitly condemned the enclosure movement in either her fiction or her letters."

So.... what is the conclusion? Was Austen an anti-enclosure radical? Given the slight evidence of her private letters, I don't think she felt that strongly about the issue.

Dr. Kelly's theory of Jane Austen's secret radicalism comes down to the assertion that Austen was a radical but she couldn't show it. We can never know if Austen wasn't explicit for fear of the consequences. Kelly's theory, as I've mentioned before, is non-falsifiable.

Since Austen's references to land enclosure are so fleeting and indirect, her novels aren't the first place you'd turn to if you want to read fictionalized accounts of how land enclosure affected the working class. An old favourite of mine is The Camerons by Robert Crichton (1972), which features the Highland Clearances and the harsh life of Scottish miners.

If I come across any other writings of Austen's time which protests against land enclosure, I'll share that information here.

Update: I re-visit the topic of hedges and land enclosure in my 100th blog post.

Ellen of the Reading Jane Austen podcast discusses land enclosure, the agrarian revolution, and Austen's social activism, if any, in two episodes dealing with Pride & Prejudice. Here at 36:29 and here at 51:30.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed