| Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. |

“The presence of militia in the novel… introduces layer upon layer of anxiety.” Dr. Helena Kelly

“The presence of militia in the novel… introduces layer upon layer of anxiety.” Dr. Helena Kelly In an earlier post, I mentioned that I don't think her novels are about political or social themes. Jane Austen is a moralist who critiqued the world around her, but she's not a revolutionary.

The first example I’m going to look at in depth involves Dr. Helena Kelly's take on the hidden meaning of the militia in Pride and Prejudice.

According to Dr. Kelly, when the militia marches into town, the reader should be feeling an uncomfortable tingle up the back of his neck.

"The militias aren’t in the novel to provide young men for the five unmarried Bennet girls to dance with; they bring with them an atmosphere that is highly politically charged; they trail clouds of danger—images of a rebellious populace, of government repression, and, more distant but insistent nevertheless, of the fear of what might happen if the men in the militia, the troops, mutiny."

So, are we supposed to feel uneasy about the militia in Pride and Prejudice?....

Austen doesn't dwell on this sordid side of things. Instead, Kitty and Lydia go into a tizzy over the officers. Even Mrs. Bennet is excited, ("I remember the time when I liked a red coat myself very well—and, indeed, so I do still at my heart") and Mr. Bennet rolls his eyes and goes to his study.

And Pride and Prejudice isn't the only novel which shows a regiment encamped in a British village to the delight of its female inhabitants. In the opening scenes of Eglantine, or the Family of Fortescue, (1816), Lucy and Sophia Mansel are pouting over the departure of a regiment.

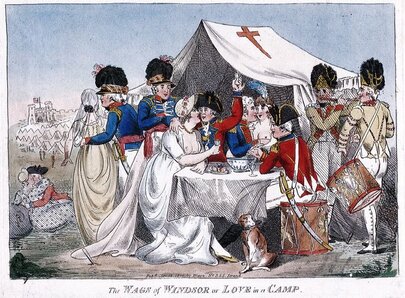

Military-themed fashion was popular during the Regency era

Military-themed fashion was popular during the Regency era Actually, putting down seditious uprisings was the reason for having a militia. Nothing unspoken about it. It was right there in the founding legislation. There was no police force in Regency England, nor could the economy of that time sustain a standing police force everywhere, so gentlemen in every county were appointed officers of the militia and able-bodied men were trained at regular intervals, to be called out in the event of emergencies, such as popular rebellion.

Suppose that a riot erupted in Meryton and the officers were ordered to put it down. Kelly starts with the assumption that the novel-readers of Austen's time would identify not with the officers, but with the rioters. Really? Austen is writing for the propertied, monied, class, not landless peasants.

After presenting the militia as threatening, Kelly flips the argument around and suggests Austen wants us to feel sympathy for the soldiers, because “a private had been flogged,” and flogging is a cruel punishment. “There’s a nasty underbelly to all these fun and games.”

Whether we are talking about militia putting down a protest, or soldiers being flogged, we must remember that Georgian sensibilities were not as tender as ours, and certainly not as tender as Dr. Kelly's. Flogging was a widespread practice in the army, in the navy, and it was also used as a punishment in civil and ecclesiastical courts.

Austen uses the same device in Emma to explain how Mr. Weston met his first wife, who was his social superior. He was a captain. Are we to feel anxious and uneasy about Mr. Weston as well? Are we to picture this genial man flogging his troops?

We can look to the reactions of Austen's characters to see if Austen approves or disapproves of something. Is there any evidence that the militia have made the people of Meryton uneasy? Does anybody react with hostility? Even after Wickham elopes with Lydia, Mr. Bennet speaks of taking Kitty to a review (a large gathering where the soldiers march on display), as a reward for good behaviour.

Finally, how can Kelly square her theory that Austen and her readers would be hostile to the militia with the following passage in Northanger Abbey?

The hero of Northanger Abbey, Henry Tilney, is funny and fanciful and satirical. He is taking a walk with his sister Eleanor, who is intelligent, kind and thoughtful. And with them is the heroine, young Catherine Morland. They are all nice, good people.

Catherine mentions that she’s heard about a new gothic horror novel: “I have heard that something very shocking indeed will soon come out in London.”

Eleanor misunderstands her and thinks Catherine is speaking of a pending mob uprising. “You speak with astonishing composure! But I hope your friend's accounts have been exaggerated; and if such a design is known beforehand, proper measures will undoubtedly be taken by government to prevent its coming to effect.” Henry clears up the misunderstanding in his jesting way.

| "Dear Eleanor, the riot is only in your own brain. The confusion there is scandalous. Miss Morland has been talking of nothing more dreadful than a new publication which is shortly to come out... do you understand? And you, Miss Morland—my stupid sister has mistaken all your clearest expressions. You talked of expected horrors in London—and instead of instantly conceiving, as any rational creature would have done, that such words could relate only to a circulating library, she immediately pictured to herself a mob of three thousand men assembling in St. George's Fields, the Bank attacked, the Tower threatened, the streets of London flowing with blood, a detachment of the Twelfth Light Dragoons (the hopes of the nation) called up from Northampton to quell the insurgents, and the gallant Captain Frederick Tilney, in the moment of charging at the head of his troop, knocked off his horse by a brickbat from an upper window. Forgive her stupidity. The fears of the sister have added to the weakness of the woman; but she is by no means a simpleton in general.” |

As Paula Byrne notes in her biography of Austen, It's quite possible that Tilney's description is based on the frightening experience of her cousin Eliza DeFeuillide, who was caught up in a riot in London in 1792, causing her to miscarry. If so, it's a very light-hearted handling of an event which terrified her cousin, whose driver was injured by a flying projectile.

It’s also possible that Austen revised the novel before her death. Although Northanger Abbey was written shortly after the French Revolution, it was published posthumously. Henry Tilney could be making a glancing reference to the Spa Fields riots of 1816, when a radical named Arthur Thistlewood attempted to raise a mob to storm the Tower of London.

It’s possible too that if Austen had lived long enough to hear about Peterloo, when armed cavalry rushed into a large peaceful crowd, hacking and slashing, she might have moderated her views. But Peterloo occurred almost three years after Austen’s death.

However, based on the the text, it does not appear that the author of Northanger Abbey feels any sympathy for popular uprisings, or assumes that her readers would, either.

Previous post: Secret Radical Redux Next post: more on Pride and Prejudice--is it anti-nobility?

| In 1794, when the alarm about an invasion from the French was at its height, Jane Austen’s father donated the considerable sum of five Guineas to the County of Southampton Internal Defence of the Kingdom. In the final book of my Mansfield Trilogy, some of my main characters are caught up in the chaos and tragedy of the Peterloo Massacre when an unprofessional militia attacked a peaceful protest. Click here for more about my books. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed