| “In this novel we certainly find much to admire, and much even to approve, but there are some things so improper as to disgrace and discredit the whole work… every person of good morals will concur in reprobating the indelicacy of certain passages…” -- Review of Amelia Mansfield, 1809 |

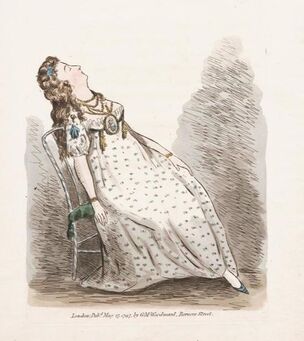

"Art of Fainting in Company" by G.M. Woodward, 1797

"Art of Fainting in Company" by G.M. Woodward, 1797 Well, I was curious, so I read the novel to see what parallels there might be to Mansfield Park. I’ll get back to that connection later, but first, here’s a book review with spoilers:

This is a sentimental novel in which the author, Sophie Cottin, skillfully arranges her characters in situations which exploit emotion and pathos to the fullest. I really have to admire the talent with which the author set up the doomed romance and the facility with which she wrung every last possible drop of angst, hope, and despair out of the various misunderstandings and obstacles.

The whole fraught unfolding of events drew me in and kept me turning the pages to find out what would happen—despite not respecting the heroine and especially not liking the hero (for reasons I'll explain).

The ideal of romantic love; Marianne (Kate Winslet) pines for Willoughby in the 1995 Sense & Sensibility

The ideal of romantic love; Marianne (Kate Winslet) pines for Willoughby in the 1995 Sense & Sensibility “Oh, Adolphus! did you know all her enchanting powers; were you to see that lovely bashfulness, that tender emotion, that affecting serenity which her heavenly features alternately express; could you conceive the force of her eyes, the charm of her smiles; were you to behold that union of melancholy and vivacity, that modest mien and that exquisite shape; (etc., etc.)….” *

Ernest Woldemar, the hero of Amelia Mansfield, is a horrible person in childhood; we are told he becomes better as he gets older. Amelia's first marriage was unhappy; her husband's dead. Ernest renews his acquaintance with Amelia under false pretenses, coming to the chateau where she lives with her late husband's uncle.

Ernest lies about his true identity, lies repeatedly, uses his friend to cover up for him, and hangs around after his host has told him to leave. He emotionally blackmails Amelia into meeting him in the middle of the night, vows eternal love and pressures her to sleep with him, which she does. This leads to Amelia's doom, 18th-century-style.

Ernest pursued Amelia when he was not free to marry her. In that respect the main conflict of Amelia Mansfield resembles Elinor's situation in Sense & Sensibility. And of course Marianne Dashwood is a sentimental heroine who almost dies of unrequited love. But Austen has Marianne explicitly reject her self-martyrdom, apologize for her selfishness and promise to live for her family. Amelia, on the other hand, pursues her obsession with Ernest, falls ill, and dies. So the hero ends up causing the disgrace and death of the heroine.

Austen doesn’t romanticize death the way Mme. Cottin does. Ernest's friend Adolphus remarks: ‘our joys [are] so transient, and our sorrows of such long duration—Ah! If man in his cradle could foresee the woes inseparable from existence, where is he who, to escape so fatal a present, would not hasten back into annihilation?”

Detail of "La Lecture" by Pierre-Antoine Baudouin

Detail of "La Lecture" by Pierre-Antoine Baudouin Mme. Cottin features prominent countervailing voices in Amelia Mansfield as well. Amelia and Ernest each have a chief correspondent; Amelia has her older brother Albert, who is a bit of a wet blanket, and Ernest's friend Adolphus is a stern, unemotional type. They serve as a Greek Chorus of disapproval.

“I no more comprehend your language than your situation…” Adolphus tells Ernest, “so much does your conduct augment the contempt I have ever felt for this ridiculous phrensy.”

Though lip service is paid to conventional virtue and morality, the hero and heroine sacrifice everything, even their lives, to the ideal of romantic love. “To die for love!” as Marianne exclaims to her mother in the 1995 Sense & Sensibility movie. "What could be more glorious?”

In addition, Cottin makes it clear that Amelia experienced sexual pleasure in her union with Ernest, with references to “a mutual fire” which “darted through our veins,” and “celestial felicity” and “those heavenly raptures which I am unable to describe."

The sentimental novel, in short, is a subversive novel in terms of 18th-century mores. The review of Amelia Mansfield In the Quarterly Review included a lengthy editorial about the dangers of reading this kind of novel (The entire review is here). Novels of this sort were an unrealistic and dangerous diversion and particularly improper for young girls.

The reviewers praised a previous work by Mme. Cottin (Elizabeth: or the Exiles of Siberia) as being upright and excellent, but said they could not recommend Amelia Mansfield. “It is extremely improper that such characters as Ernest and Amelia should be held up, as they evidently are, to our love and esteem.”

Blanche on the lure of being a romantic heroine

Blanche on the lure of being a romantic heroine Amelia also has a sprightly sidekick named Blanche, who is engaged to marry Amelia's brother. But Amelia and Blanche are separated for almost all of the novel, and Blanche gets few opportunities to display her sprightliness.

And then there is the kindly old uncle who gives Amelia a home at the beginning of the novel. She repays him by dragging him into her romantic drama, with the crying and the fainting and moodiness and the illness, then she runs off to find Ernest (after realizing (1) she's pregnant and (2) he has lied to her TWICE about what his real name is) and she leaves her little boy with the uncle. The poor kid is traumatized at being abandoned by his mother. Amelia never seems to consider the effect of her behaviour on others. Little Eugene has already learned to refer to himself in the third person in moments of high drama, ("O my mother! Why will you sleep so long, and not answer poor Eugene?") and pretty soon he'll pick up on the fact that he's supposed to switch from "you" and "your" to "thou" and "thy," as everybody else does.

“Oh, Mansfield! Inconstant Mansfield! whilst thy talents rendered thee the idol of every female; whilst intoxicated by their praises, and immersed in a vortex of pleasure, thou forgottest that thou hadst sworn to love none—but Amelia, she, confined to her lonely retreat, wept in secret, and sent up fervent prayers to heaven to put a close to an existence, which thy perfidy had rendered a torment.”

The resemblances between the two novels are superficial: Both girls live with their uncles and both are very attached to their older brothers. Amelia, like Fanny, is under strong pressure to marry a man she dislikes. Well, many 18th century novels and plays are about girls in this situation. If the girl gets to marry the man she loves, it's a comedy. If she doesn't, it's a tragedy.

The “Mansfield” in Amelia Mansfield’s name comes from the very brief and unhappy marriage at the beginning of the novel. Amelia's marriage to Mr. Mansfield is told in flashback and it’s merely a prologue to the main event; the author is setting up her heroine for the persecutions and suffering she will undergo as a result of the implacable hatred and resentment of Ernest’s mother, the Countess de Woldemar. She was angry when Amelia refused to marry Ernest, and Ernest originally intended to seduce Amelia and then dump her and reveal his true identity, to punish her. The Quarterly Review points out “This was certainly a design which no one who deserved the name of a gentleman could entertain for a moment; yet with unpardonable inconsistency, the author evidently intends that Ernest should be regarded as a man of high and generous spirit."

And as I said, the sentimental novel is a different genre altogether from Austen’s comedies of manners. I don't think Austen would give a shout-out to a novel that portrays people behaving in ways Austen would never endorse.

I've written about other now-obscure female writers of Austen's time. For more, click on the "Authoresses" tab in the Categories section on the right-hand side of the blog.

Previous post: Father's Day Next post: Constance, the weeping heroine.

| * Ernest's rapture over Amelia resembles a speech in Mansfield Park from Henry Crawford to his sister about the charms of Fanny: “Had you seen her this morning, Mary, attending with such ineffable sweetness and patience to all the demands of her aunt’s stupidity, working with her, and for her, her colour beautifully heightened as she leant over the work, then returning to her seat to finish a note which she was previously engaged in writing for that stupid woman’s service...” Maybe Austen is copying Cottin here, but I think it's more likely that both authors are drawing on established forms. Austen is showing Henry in love with the idea of being in love. As Mary Crawford says of him: “Henry is quite the hero of an old romance, and glories in his chains.” |

| If William Godwin and his wife are to be believed, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley carried on like the hero of a sentimental novel when they resisted his courtship of their daughter Mary. He was already married (but separated from his wife) when he burst into the Godwin’s home, saying to 16-year-old Mary, “They wish to separate us, my beloved; but Death shall unit us.” He offered her a bottle of laudanum. “By this you can escape from tyranny; and this, ‘taking a small pistol from his pocket, ‘shall reunite me to you.’ In my novella, Shelley and the Unknown Lady, Shelley and Mary are living in Italy, but the bloom is off their romance. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed