|

- they were more thrilling than the real world, and therefore distracted people from the real world.

- they were so romantic that they gave young people, especially young women, unrealistic ideas about love and life.

- they glamorized vice.

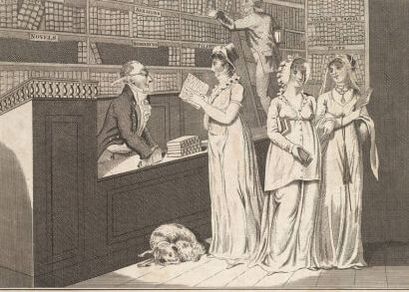

A Circulating Library

A Circulating Library Novels as we understand the term emerged as a genre in English in the 18th century. By the time Jane Austen was old enough to read novels, they were widely available through circulating libraries, for which one paid a subscription fee. Books were much more expensive to buy as a percentage of household income than they are today. Austen's father acquired a large library and I have a feeling that books were his weakness.

Of course the Austens' library was comprised of serious works, such as histories and essays. However, Jane Austen described her family as being "great Novel-readers and not ashamed of being so."

In 1750, Samuel Johnson (Austen's favourite prose author) wrote an essay about the dangers of novels for inexperienced young people. He pointed out that this new and popular type of book was based on real life: "The works of fiction, with which the present generation seems more particularly delighted, are such as exhibit life in its true state.... it is therefore precluded from the machines and expedients of the heroic romance, and can neither employ giants to snatch away a lady from the nuptial rites, nor knights to bring her back from captivity; it can neither bewilder its personages in desarts, nor lodge them in imaginary castles."

Nobody, in other words, could mistake the old romances of knights and castles for real life, but, modern novels were different. Because they are based on real life, they might be mistaken for real life: "These books are written chiefly to the young, the ignorant, and the idle, to whom they serve as lectures of conduct, and introductions into life. They are the entertainment of minds unfurnished with ideas, and therefore easily susceptible of impressions; not fixed by principles, and therefore easily following the current of fancy; not informed by experience, and consequently open to every false suggestion and partial account."

Austen was not concerned that she herself would be carried away by romantic novels. She enjoyed them, but laughed at them, and wrote parodies of them, as we know. When she visited London in 1796, she wrote jokingly to Cassandra, "Here I am once more in this scene of dissipation and vice, and I begin already to find my morals corrupted," a funny reference to the way that novels often contrasted country virtue with city vice.

Playwright Samuel Foote, probably getting a bit of his own back, made fun of the critics. In his 1764 farce, The Liar, an irresponsible young man who has left Oxford to enjoy himself in London talks with his confederate Papillion, who is pretending to be his private tutor. Papillion describes some of the many jobs he's held in the past:

| Papillion: Upon quitting the school, and first coming to town, I got recommended to the Compiler of the Monthly Review… in obedience to the caprice and commands of my Master, I have condemned books I never read, and applauded the fidelity of a translation, without understanding one syllable of the original. Wilding: Ay! why I thought acuteness of discernment, and depth of knowledge, were necessary to accomplish a Critic. Papillion: Yes, Sir: but not a monthly one. Our method was very concise: we copy the title page of a new book: we never go any farther; if we are ordered to praise it, we have at hand about ten words, which, scattered through as many periods, effectually does the business: ay, “laudable design, happy arrangement, spirited language, nervous sentiment, elevation of thought, conclusive argument; if we are to decry, then we have “unconnected, flat, false, illiberal stricture, reprehensible, unnatural.” and thus Sir, we pepper the Author, and soon rid our hands of his work. Wilding: How came you to resign this easy employment? Papillon: It would not answer. Notwithstanding what we say, people will judge for themselves. Our work hung upon hand, and all I could get from my publisher was four shillings a week and small beer. |

And in their prefaces, they assured their readers that their novels were very moral. One author, for example, promised that his book Douglas, or the Highlander, was intended to "expose folly, vanity, frivolity and vice, and to do justice to wisdom and virtue." The preface of Constance explained the novel: “promulgates no doctrine that may not be received with advantage… it patronizes no vice, it rewards virtue, and it inculcates a truth, which it were to be wished abler pens would enforce, that a dominion over our passions is in all instances conducive to our happiness.” Jane West’s A Gossip’s Story was “intended, under the disguise of an artless History, to illustrate the advantages of consistency, fortitude, and the domestic virtues; and to expose to ridicule, caprice, affected sensibility, and an idle censorious humour.”

Jane Austen did not write prefaces for her novels, with the exception of Northanger Abbey, and that was an explanation about the long delay in publishing the novel. The preface is an opportunity to come out from behind the curtain and address the audience directly, but Austen did not avail herself of it.

Previous post: The Weeping Heroine Next post: The Dangers of Reading Novels, part two

| “With glittering prose, this novel recreates the darkest corners of American life in an unforgettably tender portrait of the fragile consequences of ambition and regret.” If you need to write a review for some modern literary fiction, nothing could be easier; just use my handy-dandy Literary Fiction Review Generator, available here at The Rambling. |

| My Mansfield Trilogy, based on Mansfield Park, features an author who writes futuristic novels in Regency times. Mr. Gibson's first novel was Steam & Sagacity. "Even critics who picked up the work, intending to condemn and insult the writer, found much to praise in his fantastical tale of a future era when steam machines relieved humanity of tedious and dangerous toil, when people could travel swiftly around the globe with locomotives and steam ships, and better commerce and intercourse between the nations of the world curbed the cruel excesses of despotic powers." Click here for more about my books. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed