Awkward dinner-party conversation

Awkward dinner-party conversation Now, I’m back to banging the drum about the fact that many, many, 18th-century authors discussed slavery more extensively and explicitly than Jane Austen, yet modern academia has focused a giant microscope on references to slavery (or imputed references) in her novels. The opinions of the beloved author are a matter of intense investigation and speculation. I believe this is because some people can only read Austen with a self-approving conscience if they can say she was an ardent abolitionist. As professor Patricia A. Matthews wrote, some of her "students who were Jane Austen fans felt instantly complicit for liking stories where slavery might be present without an explicit critique."

Well, Moore is explicit. You don't need the aid of scholarly divination to understand John Moore's position on slavery. His attitude doesn't have to be sifted and searched for. He condemned slavery in his first novel, Zeluco, and he wrote a bold and shocking conversation about slavery in Edward. The tone of his criticism is as harsh as the writer (Jonathan Swift) that he invokes. In fact, it will be difficult reading for some, so be forewarned...

In Volume II, chapter 57 of Edward, Moore assembles some major and minor characters at a dinner party at the home of Sir Mathew Maukish. We first meet Sir Mathew in Volume I when he runs over a crippled soldier with his carriage. A dozen ladies and gentlemen are present at the banquet, but not the hero, Edward.

Salmon fishing

Salmon fishing Mr. Barnet, a lazy gourmand, whom we met in my previous post. He isn’t very bright and like Austen’s Mr. Rushworth, is not very much aware of this fact.

Mr. Wormwood, the sardonic neighbour of the Barnet family. He likes eating at Mr. Barnet’s well-appointed table but takes subtle digs at him.

Mr. Temple, a respectable, virtuous clergyman and a moral arbiter of the novel.

Colonel Snug. Moore quotes Swift in describing him: "To all mankind a constant friend, provided they had cash to lend."

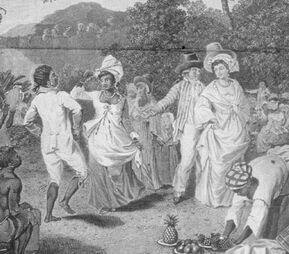

Mr. Grinder, an overseer of a slave plantation in the West Indies who has “accumulated a considerable fortune” and plans to buy property in England. He is looking at some land owned by Sir Mathew, which is why he’s been invited to dinner.

The conversation starts with Mr. Temple declining to eat any salmon when he learns that it’s been “crimped,” meaning that its flesh was slashed and it was left alive in water for a few hours before being cooked. This is a technique which is supposed to improve the texture of the flesh.

The guests debate the topic of animal cruelty with their hosts. Mr. Barnet adds that it’s too bad carnivorous animals aren’t tasty to eat, because “it would furnish a greater variety to the table and would be a comfort to tender-hearted people like my wife who feel some compunction in killing lamb and chicken.”

“’Might we not be in danger of eating one another?’" asks Mr. Temple.

This jest reminds Colonel Snug of Jonathan Swift's famous essay A Modest Proposal. He remarks: "there was a proposal for bringing the children of poor people in Ireland to market in times of scarcity.”

Here's where it gets weird...

Here's where it gets weird... The other gentlemen are amused to discover that Mr. Grinder isn't sure whether or not Swift's essay is a satire. Perhaps Swift really did think the Irish should sell their children to be eaten!

Wormwood, in a mischievous mood, tries to persuade Mr. Grinder that Swift really meant what he said: "for that treatise is written with an air of great seriousness.'"

| “‘I question much,’ replied Grinder, 'whether it could be legally adopted in Great Britain or Ireland, even during a famine.’ “’But in case of a famine in the West Indies?’ rejoined Mr. Wormwood. “‘Why, why, even there,’ answered Mr. Ginder, after a little demure, ‘I think the scheme should be permitted to extend only to a man’s indisputed property, which he has honestly bought with his money, or bred on his estate, and which he has a right, by the laws of God and man, to dispose of as he pleases, and as is most for his advantage.’ “‘In which you call a man’s indisputed property... do you comprehend the children of his negro slaves?’ said Wormwood. “‘I unquestionably do,’ replied Grinder. “‘I expected there would be a clause in their favour,” said Wormwood. “‘For my part,’ cried Barnet, [who doesn’t understand that Wormwood is just stringing Mr. Grinder along] ‘hang me if I would not rather starve than eat a morsel of either a white child or a black.’ “‘If all the world were as squeamish as you, brother,” said Mr. Temple, “the black children would reap no benefit from the clause which Mr. Grinder would leave in their favour.’ “‘In their favour!’ repeated Grinder. “‘Yes, Sir,’ rejoined Mr. Temple, ‘I should think it a favour to slaughter them during their infancy, rather than rear them to the miserable lives the generality of them do.’ |

Mrs. Beeton's Cookbook

Mrs. Beeton's Cookbook Back to the matter of the historical and cultural significance of the slavery debate: as I’ve been saying, if you read 18th century literature to interrogate the author's attitude about slavery, (as opposed to reading literature for its excellence) I think studying the previous conversation in Edward makes more sense than another deep dive into the “dead silence” of Mansfield Park.

"Austen is an author who takes on some of the central issues of her age," declares historian Robert Morrison. "I admire her for bringing [the issue of slavery] up in Mansfield Park." Well, compared to who? Here are two more posts which extensively quote 18th-century novels that contain discussions or depictions of slavery which are far more explicit than Austen in "bringing it up." These authors deserve admiration as well, don't they?

Previous post: Taking the novel seriously Next post: "What excellent potatoes"

| I have written previously about the fact that even authors who were pro-abolition were not above using the West Indies (specifically West Indian fortunes) as a plot device. And as an example of treating the West Indies with levity, there is a minor, non-speaking character of colour in Edward, referred to only as “The Mulatto.” "The Mulatto" is the heir of a West Indian fortune who has come to England to live in splendour. In keeping with many portrayals of West Indians in novels of this period, he is a figure of some ridicule. "The Mulatto" has more money than taste. He's gullible. He over-decorates his house. His morals are also suspect because he keeps a string of mistresses. His money is welcome but he is not welcome as a dinner guest. John Moore's novel has a large cast of characters and some of them, like "The Mulatto," have virtually no effect on the plot. "The Mulatto" could have been omitted from the novel entirely. Why is he even there? Moore was indignantly against slavery but he still used a nouveaux riche West Indian as a target of satire. We have no idea what role Miss Lambe was going to play in Sanditon, although it is generally assumed that the portrayal of the "chilly and tender" heiress was going to be a sympathetic one. Patricia A. Matthews, "Jane Austen and the Abolitionist Turn." Texas Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 61 no. 4, 2019, p. 345-361I Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed