| Some modern readers who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Clutching My Pearls is an ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. |

A Vicar, detail of Rowlandson cartoon, 1785

A Vicar, detail of Rowlandson cartoon, 1785 Some scholars have pointed to Austen's clergymen as evidence that Austen was critical of the Church of England. Was it daring or dangerous to be critical of the clergy? Was it radical? More importantly, did she actually oppose the Church of England, as discussed in my previous post?

In fact, jokes and complaints about incompetent or corrupt clergy were quite prevalent in conversation and literature during the long 18th century. One of the first English novels, Tom Jones, featured a sadistic clergyman, Mr. Thwackum.

The cartoon showing a clergymen enjoying an after-dinner snooze, suggests that it was acceptable to poke fun at clergymen, within certain limits. A copy of this print was purchased by the Prince of Wales. (The vicar's foot is bandaged and resting on a pillow because he's suffering from gout caused by his over-rich diet.)

Austen deliberately included several explicit discussions about the clergy in Mansfield Park. Perhaps these might serve as a better guide to her opinions...

The arguments against clergymen are voiced by Mary Crawford--the worldly, cynical girl from London--and the arguments in favour are put forward by Edmund Bertram, who is the hero of the novel (though many readers think he's a prig and a bore.)

Edmund calls Mary Crawford's criticisms of the clergy "commonplace," which suggests that it was not at all unusual in Austen's time to air the points that she makes. Even so, I was surprised to find, Mary's exact same points in the memoirs of Henry Hunt, a radical politician. I am not suggesting Hunt cribbed his dialogue out of Mansfield Park. I think the resemblance shows just how commonplace the censures were.

Henry Hunt was convicted of seditious conspiracy. He published his memoirs from prison in 1820 (which in itself tells us something about what kind of remark got censored in Regency England, and what didn't.)

Just as Jane Austen puts the anti-clergy arguments into the mouth of Mary Crawford, Hunt's vehicle is his father, who appears to have been a prosperous country squire, perhaps something like the older Mr. Musgrove in Persuasion.

The first charge against the clergy is lack of ambition and laziness. Mary Crawford complains, “It is indolence, Mr. Bertram, indeed. Indolence and love of ease; a want of all laudable ambition, of taste for good company, or of inclination to take the trouble of being agreeable, which make men clergymen. A clergyman has nothing to do but be slovenly and selfish—read the newspaper, watch the weather, and quarrel with his wife. His curate does all the work, and the business of his own life is to dine.”

Hugh Blair, 1718 - 1800, Scottish minister and author of popular sermons

Hugh Blair, 1718 - 1800, Scottish minister and author of popular sermons While Henry Hunt's mother tells her husband, "[R]eally my dear, although there is too much truth in the picture you have drawn, yet you have been a little too severe upon the clergy, when speaking of them in the mass. There are many excellent and worthy men, who follow the precepts of their great master, who are an ornament to that society to which they belong... [and] do great credit to the profession..."

"Do not tell me about ornaments to society," the father replies, "the best of them are drones of society [because]... they feed upon the choicest honey, collected by the labour of the industrious bees..."

This part about the bees and honey is a reference to tithes. Clergymen were usually supported by taking a percentage (traditionally ten percent) of the food and other manufactures of the parish, known as tithes.

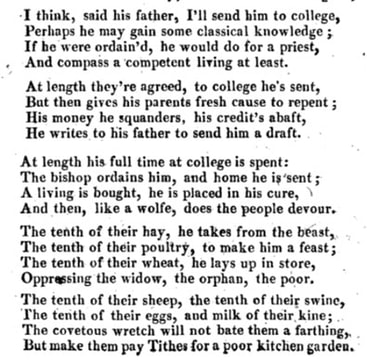

| There was, naturally enough, a lot of resentment about tithes, as it involved declaring all the produce of your farms and fields. An angry manifesto titled "Tithes Abolished and Priestcraft Detected," (1814, the same year as Mansfield Park) inveighed against tithes and also against dissolute and lazy clergymen. The author, Edward Tovey, who appears to have been a fire-and-brimstone Evangelical, attacked the system of selecting clergymen, because young men with absolutely no vocation for the church could get a degree and then be ordained. In the poem excerpted at left, the parents of a wild and not-very-bright child are at a loss how to train him for a profession, and decide to set up him as a clergyman. Once ordained, he oppresses his flock with his demands for tithes: "The covetous wretch will not bate them a farthing, But make them pay Tithes for a poor kitchen garden." |

What is noteworthy is that Mary Crawford--who represents the point of view of a worldly cynic--makes the same criticisms as a country squire (Henry Hunt's father) and an evangelical like Edward Tovey. These censures of the clergy were commonplace, indeed. There was obviously an ongoing social debate about tithes, pluralism (the practice of holding more than one living), absentee clergymen, incompetent clergymen, and so forth. Participating in that conversation did not mark you out as radical.

The starving, downtrodden curate works for the selfish clergymen in "A Clerical Alphabet."

The starving, downtrodden curate works for the selfish clergymen in "A Clerical Alphabet." Henry Hunt's father tells him, "All that will be expected of you is to read prayers, and preach a sermon, which will cost you three pence a week." Edward Tovey also accuses the clergymen of buying his sermons "at twice ten pence a score."

Many clergymen left the sermonizing to their curates, a subordinate who was typically paid a pittance out of the income of the parish. In Sense and Sensibility, Mrs. Jennings exclaims "Then, Lord help 'em! how poor they will be!" when she thinks Edward Ferrars will marry on a curate's salary.

A detail from "A Clerical Alphabet." showing a greedy clergymen with his tithes. Click on the photo to see the complete cartoon.

A detail from "A Clerical Alphabet." showing a greedy clergymen with his tithes. Click on the photo to see the complete cartoon. Henry's brother-in-law Dr. Grant, also a clergyman, talks to Edmund about “how to make money; how to turn a good income into a better." Dr. Grant is giving Edmund tips about the living he is about to step into; in other words, how to collect the tithes and improve the yield of his own acreage.

Well, if tithes are all right with Edmund, they are all right with Fanny, our heroine. And Jane Austen, as we recall, laughed at the suggestion that she should include the abolition of tithes in one of her novels and wrote a little satire about it. We might also recollect this is how her father, whom she loved and respected, supported his family.

We might also recollect that in Protestantism, a clergyman is not to be regarded as infallible. The individual has their own relationship with God. As Fanny Price says, with typical Austenian euphemism, "We have all a better guide in ourselves, if we would attend to it, than any other person can be."

The Church of England denied the Methodist minister John Wesley a pulpit, so he preached in the open air.

The Church of England denied the Methodist minister John Wesley a pulpit, so he preached in the open air. Edmund answers, "A clergyman cannot be high in state or fashion. He must not head mobs, or set the ton in dress." As noted, when Mary says, "a clergyman is nothing," she is referring to his status in society. There is no "heroism, danger, bustle, fashion" in being a clergyman, as opposed to being a soldier or a sailor. It's an unmistakable sign (well, unmistakable to everyone but Edmund, that is) of Mary's utter worldliness. She is entirely unsuited to become a clergyman's wife. She also denies that the clergy can really have much effect on public morals--how much good can a few sermons do, especially when contrasted with the actual behaviour of clergymen who do not practice what they preach?

Edmund replies with the "respect the office, not the person," argument.

"No one here can call the office nothing... The manners I speak of might rather be called conduct, perhaps, the result of good principles; the effect, in short, of those doctrines which it is [the clergymen's] duty to teach and recommend; and it will, I believe, be everywhere found, that as the clergy are, or are not what they ought to be, so are the rest of the nation.” And he makes the same point that Mr. Hunt's mother makes--a clergyman has the power of doing good. In fact, Edmund goes much farther: "But I cannot call that situation nothing which has the charge of all that is of the first importance to mankind, individually or collectively considered, temporally and eternally, which has the guardianship of religion and morals, and consequently of the manners which result from their influence."

From this speech, Mary should have understood that Edmund actually believed in the doctrines he was speaking of. Despite his use of euphemisms, he took his faith seriously. (I think Jane Austen's gravestone proclaims that she and her family did, as well.)

Further reading

Further reading These last two posts have addressed the question of whether Austen was doing anything risky or daring by putting Mr. Elton and Mr. Collins in her novels, or if her foolish clergymen should be interpreted as Austen's alienation from the Church of England. But I did not revisit Dr. Kelly's assertion that Mansfield Park is a protest against the sugar plantations owned by the Church of England. Since Austen doesn't mention these plantations in the novel--for that matter she doesn't even mention sugar--Kelly's assertion rests on the symbolism and allusion she claims to find. I did touch on this briefly in the past, and will write more about Mansfield Park in the future.

Previous post: Religious decorum Next post: Rule Britannia

| Update: now that I've read a lot of novels from the long 18th century, I've realized that modern scholars like to attribute some characteristic to Jane Austen (such as the emphasis on class and income), without acknowledging (or perhaps even realizing?) that the characteristic was not at all unusual for her time. For this and other examples of erroneous thinking in modern scholarship, see my six questions scholars should ask themselves. Dissenting Protestants like the Quakers were at the forefront of the campaign to end the slave trade. In my Mansfield Trilogy, Mrs. Butters, the widow of a shipbuilder who made ships for the slave trade, gives much of her fortune to the abolition campaign. Click here for more about my books. Update: I've done a series about the portrayal of Methodism in novels of this era. Wow, they sure didn't like Methodists... |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed