| Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the introduction to the series. |

When Catherine Morland talks herself down from her Gothic fantasies in Northanger Abbey, she recalls what Henry Tilney told her: "Remember, we are English."

Austen's narrative voice adds, (in phrases a bit wittier than we would expect to find in Catherine's interior monologue): "But in the central part of England there was surely some security for the existence even of a wife not beloved, in the laws of the land, and the manners of the age. Murder was not tolerated, servants were not slaves, and neither poison nor sleeping potions to be procured, like rhubarb, from every druggist." ...

| | Yes, it was great to be English at this time in history,. Many Englishmen and women took pride in being the ones who stood against Napoleon. When your country is under threat, when the other countries of Europe have been subjugated by a conqueror and you are fighting on, this would tend to increase your own patriotic zeal. It's true the Hanoverian royal family was nothing to boast about. Austen hated Prince George, appointed Regent of England during his father's mental illness. But as she looked around the globe, no other kingdom compared to England. |

A scene from "The Monk"

A scene from "The Monk" England was the centre of the universe, not just for Austen but for all her characters. When Elizabeth, or Elinor, or Emma, or Anne, refers to "everybody" or "people" as in "society," as in "what will people think," the term they use is "the world." England is the world, and more specifically, the stratum of society in which reputation and honour and decorum matters, is "the world." The rest is unimportant.

"The world" is mentioned in Pride & Prejudice 63 times, 78 in Emma. Some examples:

- "He was the proudest, most disagreeable man in the world."

- "...you have been the principal, if not the only means of dividing them from each other—of exposing one to the censure of the world for caprice and instability, and the other to its derision for disappointed hopes...”

The Origin of the Distinction of Ranks, John Millar

The Origin of the Distinction of Ranks, John Millar The craze for Gothic novels was at also its height at this time--escapist literature about exotic landscapes and passionate foreigners, including wicked (Catholic) abbots and nuns, such as shown in the scene from The Monk, above.

In Mansfield Park, Fanny Price retreats to the East Room to read Lord McCartney's account of his embassy to China.

That the people in one country were different than the people in another country, but that England was the best of countries, was a self-evident proposition in Austen's time.

People in different countries were also different in manners, customs, laws, habits. ("Manners" had a broader application than what we mean by "good manners" today). It referred more to one's style, one's way of carrying oneself. Mary Crawford tells her sister that she has "the address of a Frenchwoman" if she can persuade brother Henry to get married.

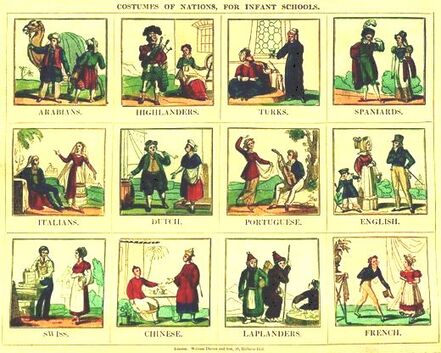

Illustrations in a children's schoolbook

Illustrations in a children's schoolbook And there was as well--naturally enough-- speculation about the causes of the differences between different nations and different parts of the globe. The people who lived in the warmer Mediterranean countries were more slothful and indolent than people in England.

There was a genuine curiosity to figure out how the world worked, to understand how and why societies organized themselves so differently around the globe. Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776 - 1788) was an exploration of how a mighty empire fell.

The Origin of the Distinction of Ranks by John Millar (1778) discussed how societies progressed from hunter-gatherer, to agricultural, and so on; how trade arose and how these economic innovations affected human relations in society at large. That is, these proto-anthropologists made connections between social organization, culture, and technological advancement. Just as it was indubitable that many empires had risen and fallen, it was also indubitable that there was such a thing as progress.

Sketches of the History of Man (1774) by Lord Kame compared the industry, the habits, even the cleanliness, of different nations and tribes. Lord Kame does not hesitate to pronounce that the Japanese were cleaner even than the Dutch, while the Tartars were crawling with vermin.

Adam Smith, in his Wealth of Nations (1776), compared and analyzed the industry and trade arrangements of different nations.

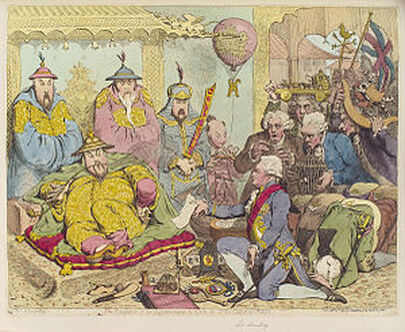

Lord McCartney's reception in Beijing

Lord McCartney's reception in Beijing This same writer was surprised to see women in the streets in Beijing. "An opinion has prevailed in Europe, that Chinese woman live secluded from view. The fact is otherwise... amid the immense concourse that were assembled to view our procession, perhaps there were more women in proportion than we should have seen in any principal town in Europe." These were probably Manchu women an ethnic group which had conquered the Han majority. Manchu women did not practice foot-binding, either.

Kendi goes on to add, "To be antiracist is to see all cultures in all their differences as on the same level, as equals. When we see cultural difference, we are seeing cultural difference—nothing more, nothing less.”

But Montague's statement differs significantly from Kendi's. Montagu says cultures can be evaluated and compared, so long as we aware of our cultural blinders. Kendi explicitly removes the possibility of holding up aspects of one culture as better or worse than another. He also conflates culture with race.

Does Kendi really see all cultures "on the same level, as equals"? Does anyone? As regards what aspects? In their social organization? In their ability to provide the necessities of life? In their technological capacity? In their tolerance for non-members? Jane Austen would not have thought this way. She would not have seen any benefit to thinking this way, either.

Jane Austen was pro-British. Does that make her a bigot? This is a painful question for some people. I for one regard Austen as a clever and well-educated woman of her time and place, who shared in the opinions of her time and place. She believed that her culture, with its written language, legal codes, specialized trades and division of labour, its educational and charitable institutions, was not merely different from, say, a nomadic tribe in the desert--it was better, and that people who lived there, even the lower classes, were lucky to be born British.

I don't feel obligated to do any special pleading for her, or grope to find a benign interpretation for Darcy's remark that every savage can dance.

| Previous post: The character of clergymen Next post: Woman, lovely woman, reigns alone In my Mansfield Trilogy, Mary Crawford is eager to go abroad once peace is declared, and like many other Englishmen and women, she goes to Italy. There she meets Percy Bysshe Shelley, who is contemptuous of the Italians because in his mind they do not measure up to their fore bearers, the Romans. I also tell this story as a stand-alone novella, Shelley and the Unknown Lady. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed