| Modern readers who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. |

| “And this is all the reply which I am to have the honour of expecting! I might, perhaps, wish to be informed why, with so little endeavour at civility, I am thus rejected. But it is of small importance.” -- Darcy to Elizabeth |

| In my previous post I looked at how important civility was to Jane Austen. Civility--treating others with consideration, patience, kindness--was a moral duty and the mark of a civilized person. The Rambling is an online periodical dedicated to scholarship about the long 18th century. A 2019 article in the The Rambling discusses a "problem" with civility, a problem that is based in its origin. Professor Urvashi Chakravarty asserts that criticizing people for uncivil behaviour is a form of racialized oppression. From "tone-policing" to complaining about rioting in the streets, calls for politeness are the hallmarks of the privileged class lording over marginalized people. | |

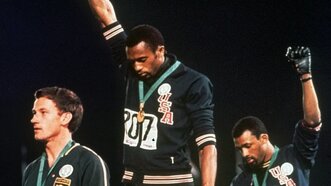

These Olympic athletes suffered socially and professionally for protesting during the medal ceremony

These Olympic athletes suffered socially and professionally for protesting during the medal ceremony In “The Problem of Civility: a Genealogy,” Chakravaty engages in some word play around the two meanings of 'civil' to build her case.

This is interesting for those of us who like to know about the etymology of words, but is there anything illuminating or profound about mixing up (or “conflating” as Chakravarty puts it) the two different definitions? Sure, I could say there is nothing civil about smashing store windows so why do we call it civil disobedience. But I haven’t proved anything. I haven’t made an argument. I’ve merely willfully ignored the two different meanings of ‘civil.’ It’s as irrelevant as pointing out that “Mrs.” is short for "Mistress." A man’s wife is not his mistress, despite the word origin.

But Professor Chakravaty does conflate the two definitions in her article. She implies that civility is deliberately used by the civil powers to marginalize and oppress. In a minute I’ll discuss the history of civility, but first, I note that Chakravaty goes beyond conflating the two different meanings of 'civil' -– she brings in 'servility' as well. “’Civil’ and ‘servile,’” she writes, “the terms slip from one to the other.”

Anne Elliot, Captain Wentworth and the Musgroves visited Lyme in Persuasion

Anne Elliot, Captain Wentworth and the Musgroves visited Lyme in Persuasion You could be the proprietor of the inn at Lyme in Persuasion, bowing and smiling, as he welcomes the visitors from Uppercross, apologizing because its "so entirely out of season," and his street is "no thoroughfare of Lyme," and there is "no expectation of company.” The inn-keeper takes his civility too far, into the realm of servility. Yes, people sometimes do this. But servility is not the same thing as civility, not in Latin, not in English and not in reality, however much slipping you do.

Professor Chakravarty also says--as though it were somehow significant--“the assonance between [‘civil’ and ‘servile’] is immediately heard, noted, ratified.”

Yes, ‘civil’ sounds a little like ‘servile.’ And ‘assonance’ sounds like ‘asinine.’ So what? This might do for analyzing a poem, but this is not an indictment of anything.

Civility is also used to divide one class from another. “To invoke the “civil” has always been [emphasis added] to demarcate the boundaries of those who do not and cannot belong: the slave, the stranger, the outcast. To rely on civility is to enact and re-enact the forms of psychic, social, and legal violence that have always separated the ‘civil’ body from the uncivil one.” (There’s that ‘conflation’ of the two meanings of ‘civil’ again).

If civility isn’t oppressing you by forcing you to behave, it’s excluding you when you don't behave the right way. Civility gets you coming and going. If there is an actual benefit, a good faith reason, for people to treat each other with politeness and consideration, Chakravarty does not mention it.

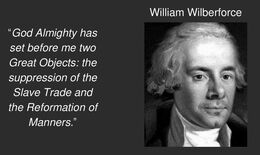

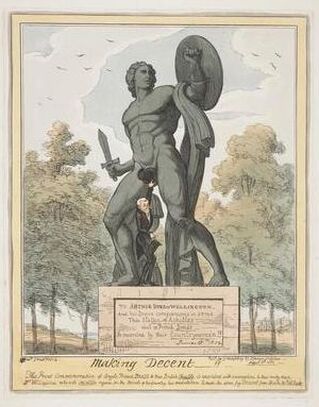

But was civility developed for the purposes of exclusion and oppression, of “civic erasure”? This would come as a surprise to William Wilberforce. “God Almighty has set before me two great objects,” he wrote in 1787, “the suppression of the slave trade and the reformation of manners.” He also formed a Society for the Suppression of Vice and we can see him lampooned in this cartoon.

By “manners,” Wilberforce meant a great deal more than keeping your elbows off the table. "Manners" is more akin to codes of conduct, which includes how we treat one another, which brings in civility.

I think we can agree that Wilberforce did not believe civility was useful for oppressing slaves. Hannah More, his ally in the abolition movement, wrote several conduct books which linked civility with morality and virtue, not servility.

Wilberforce and his allies had a profound impact on British society. The Enlightenment also played a role. And so did coffee.

According to scholars who have studied the rise of politeness in England (and yes, this is actually a field of study and debate), “politeness was associated with improvement in the sense not just of refinements of style but of moral and other reform.”

In “Politeness and the Interpretation of the British Eighteenth Century,” [The Historical Journal: Cambridge, 2002] Lawrence Klein writes that “the social and intellectual elite of Edinburgh famously adapted the pleasures of polite conversation for the pursuit of public improvement. In Scottish thinking, in particular, politeness was grafted on to schemes of human economic and political development to convey the cultural modernity of commercial polities.”

Thanks to the popularity of coffee-houses, people from different social levels began to meet and mingle, to read and discuss the news and ideas of the day, while drinking a stimulating beverage which, unlike alcohol, did not lead to public brawls. According to Professor John Mullan, in a BBC discussion of the rise of politeness, these new public spaces meant that people could "meet on equal terms” despite differences in status. And because there was a new merchant class moving up in the world, there was an interest in acquiring “polish” and good manners.

18th century tone policing: Jane Austen's father on the benefits of being polite.

18th century tone policing: Jane Austen's father on the benefits of being polite. Far from regarding civility as something to be used as a weapon against the lower ranks, Reverend Austen preached that the lowly sailors “have a claim” to kindly treatment.

Politeness was therefore both a cause and a symptom in a society that was slowly—very slowly—becoming more egalitarian. Obviously, the urbane and civilized conversation in the coffee houses excluded the people back in Jamaica who were growing the coffee. But as we have seen, the people who were reforming manners in Austen's time were the same people who were urging that slavery was a moral abomination which should be outlawed.

Miss Grey sneering at the rustic Dashwood girls for not having pronouns in their bios.

Miss Grey sneering at the rustic Dashwood girls for not having pronouns in their bios. I don't dispute that there are social penalties in our culture for uncivil behaviour, and there are also consequences for civil disobedience. But don’t all cultures have conceptions of good or bad or appropriate manners? How could a society hold itself together without norms of civil behavior? It seems very short-sighted, ahistorical and insular to conflate ‘civility’ with ‘whiteness.' To argue that civility itself is problematic is to ignore many countervailing examples from history.

| In my novel, A Different Kind of Woman, the Bristol Chapter of the Society for the Suppression of Vice steps in to stop French prisoners of war from selling obscene carvings and drawings. Click here for more about my novels. |

| Full Disclosure: The Rambling has nice and friendly proprietors, a charming snail logo, and they published my "literary novel book review" generator in their first issue, which is very funny -- check it out. For a deeper dive on the importance of civility and the history of politeness (Lord Shaftesbury), try this article by Alexander Zubatov. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed