| Modern readers who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. |

| "There was certainly at this moment, in Elizabeth’s mind, a more gentle sensation towards [Mr. Darcy] than she had ever felt at the height of their acquaintance. The commendation bestowed on him by Mrs. Reynolds was of no trifling nature. What praise is more valuable than the praise of an intelligent servant?" -- Pride & Prejudice |

Although we learn the names of some of them--Mrs. Reynolds the housekeeper at Pemberley, Wilcox the coachman in Mansfield Park--usually they’re nameless and silent. When Henry Crawford returns to Mansfield Parsonage after visiting his uncle, he brings at least two servants with him, possibly more. We just get a glimpse of them as they push Henry’s carriage into the stables.

Frank Churchill evidently brings several horses and at least one manservant on one of his visits to Highbury. After concluding his visit, Austen wrote: “The pleasantness of the morning had induced him to walk forward, and leave his horses to meet him by another road, a mile or two beyond Highbury.” His horses could hardly arrange to meet him by themselves, so there must be a groom looking after them. The horses are mentioned, the servant isn’t...

Pamela, the titular heroine of Samuel Richardson's influential 1740 novel, was a servant-girl who marries her master.

Pamela, the titular heroine of Samuel Richardson's influential 1740 novel, was a servant-girl who marries her master. It would be easy to assume that Austen didn't focus on servants because either a) she wasn't interested in servants or b) her readers weren't interested in servants.

In her private life, Austen did mention the family servants in her letters; they were part of the household. When she visited her rich brother at his grand estate, she met and befriended the governess. She left a gift of fifty pounds to her brother Henry's servant in her will.

What about (b)? Is it true that Austen's readers didn't want to hear about the servants?

Well, actually, servants made frequent appearances in literature and drama. Servants are essential as messengers and confidantes, such as Juliet's Nurse. They also provide comic relief and sometimes function as a Greek chorus, commenting on the shortcomings of their masters and mistresses. Don Quixote is considered to be one of the earliest novels ever written, (though Spanish, it was well-known in England), and Sancho Panza is right there alongside the knight.

In Lover's Vows, the play that the young people plan to perform in Mansfield Park, Tom Bertram plays a comical butler who can't resist reciting poetry. When Elizabeth Inchbold translated the play from the German, she enlarged the butler's part. Laurence Stern's extremely popular novel, Tristram Shandy, features Susan the chambermaid and Corporal Trim, servant to Uncle Toby. Pamela: or Virtue Rewarded, which was a huge hit with the public, is about an ordinary servant girl who resists her master's advances. He ends up offering her marriage. Teague, "a blundering and bewildered, hard-drinking but loyal Irish footman... regularly featured in various literary formats well into the nineteenth century," according to scholar Patricia Godsave.

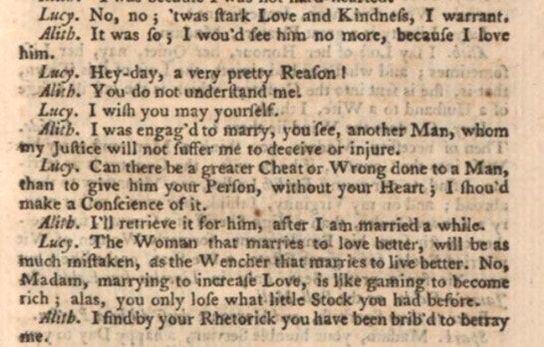

Servants weren't always stupid; they could be shrewd. There was nothing uncommon in portraying a servant as wiser and more ingenious than their master and mistress, especially in comic plays. A black servant in Laugh When You Can thwarts his master's efforts to compel a beautiful woman to commit adultery with him. The pretty, saucy, maidservant was a staple figure in plays and operettas, including Shakespeare and bawdy Restoration comedies. Lucy, a maidservant in the comic play The Country Wife has "extraordinary" agency: "she is indispensable to the love story, saves her mistress from a disastrous marriage... and acts as the deus ex machina that resolves all the problems at the end of the play."*

Austen could have written novels that featured servants, as her predecessors and contemporaries did. She could have told those stories and made the servants more visible. She didn't.

For example, let's compare the strawberry party or the picnic in Emma with this description of a strawberry picnic in The Banker's Daughters of Bristol (1824). The author describes an excursion to the countryside by some of the main characters: “Joyous and happy, the meal was no sooner terminated than our little party gave place to their servants at the rural board, and wandered as chance or fancy dictated.” Yes, the author lets us know that the servants get to sit down and eat after their masters and mistresses have eaten enough. Does Austen give us this reassurance about the nearly-invisible servants who attended at Donwell Abbey or Box Hill? She does not.

In Austen, servants serve the mechanics of the plot just as their real-life counterparts served their masters and mistresses.

Fanny Price is "greatly surprised" when, after a long delay, a servant brings in the tea things at her parents house. She had assumed the "trollopy-looking maidservant" who answered the door must surely be the subordinate servant in this two-servant household, but the girl with the tea-tray looks even worse than the first one. Austen illustrates the poverty and mismanagement in the Price household and Fanny's sinking feelings upon realizing it.

Note that Austen's narrative voice does not extend any sympathy to these two servants, apart from mentioning that their mistress does not know how to manage them properly. Mrs Price is "dissatisfied with her servants, without skill to make them better, and whether helping, or reprimanding, or indulging them, without any power of engaging their respect."

Anna Massey as Mrs. Norris in the 1983 Mansfield Park

Anna Massey as Mrs. Norris in the 1983 Mansfield Park She boasts of her "triumph" over the carpenter's ten-year-old son when she suspects him of trying to get a free meal in the servant's hall. Mrs. Norris's hypocrisy -- for she takes everything she can from the Bertrams -- is on full display here. The fact is though, that she knows the name of the carpenter's son, and his age, and undoubtedly Lady Bertram doesn't have the slightest idea who Dick Jackson is.

In Austen's world, people who talk a lot about servants or with servants are petty-minded and vulgar.

Charlotte Palmer and her mother Mrs. Jennings show off the new baby to the housekeeper

Charlotte Palmer and her mother Mrs. Jennings show off the new baby to the housekeeper Mistreatment of servants is one of the way Austen illustrates bad character. The worst employer in Austen is General Tilney, who berates a servant for not announcing Catherine Morland before she enters the room. Catherine assures him that it was all her fault --she rushed in without waiting to be announced,

"[a]nd if Catherine had not most warmly asserted his innocence, it seemed likely that William would lose the favour of his master forever, if not his place, by her rapidity."

In contrast, Sir Thomas is extremely displeased by the fact that his son Tom has ordered the estate carpenter to build a stage in the billiard-room in his absence, but none of his ire falls on the servant: "It appears a neat job, however, as far as I could judge by candlelight, and does my friend Christopher Jackson credit.”

The way characters talk about and interact with servants reveal their good and bad qualities, but these vignettes are not an obvious commentary on the unfairness of the social order. The gardener who gives Mrs. Norris a lovely specimen of heath--we don't know if he really agreed with her diagnosis of his grandson's illness. We don't know if the grandson got better. The story moves on. It wasn't about the gardener, it was about Mrs. Norris.

| "[Baddeley the butler] said, “Sir Thomas wishes to speak with you, ma'am, in his own room.” Then it occurred to [Fanny] what might be going on; a suspicion rushed over her mind which drove the colour from her cheeks; but instantly rising, she was preparing to obey, when Mrs. Norris called out, “Stay, stay, Fanny! what are you about? where are you going? don't be in such a hurry. Depend upon it, it is not you who are wanted; depend upon it, it is me” (looking at the butler); “but you are so very eager to put yourself forward. What should Sir Thomas want you for? It is me, Baddeley, you mean; I am coming this moment. You mean me, Baddeley, I am sure; Sir Thomas wants me, not Miss Price.” But Baddeley was stout. “No, ma'am, it is Miss Price; I am certain of its being Miss Price.” And there was a half-smile with the words, which meant, “I do not think you would answer the purpose at all.” Mrs. Norris, much discontented, was obliged to compose herself to work again..." Baddeley’s half-smile also betrays the fact that, however much the masters and mistresses want to hide their private affairs from their servants, concealment is impossible. |

| * Godsave, Patricia A., "The Roles of Servant Characters in Restoration Comedy, 1660 - 1685." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2018. |

For a beautifully-written, well-researched novel that portrays upstairs/downstairs life in the Regency, I highly recommend Allie Cresswell's novel, The House in the Hollow. The lives and fates of the young heroine and her servants are intertwined. The details of servant's life are integral to the plot and not gratuitous. Annie, a foundling taken in from the poor house, starts at the bottom as a scullery maid. When her young mistress is kind and encouraging, she wins Annie's undying loyalty. The reader can identify with the upstairs heroine and the downstairs heroine in this absorbing story. |

| In A Contrary Wind, the first book in my Mansfield Trilogy, we learn what Christopher Jackson, the carpenter, thinks about the time Mrs. Norris accused his son of trying to cadge a meal in the servant's quarters, and how the servants felt when she finally went away. Click here for more about my novels. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed