| Some modern readers who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. |

We also saw that her vulgar characters behave inappropriately, either by not staying properly aloof from their servants, like Lydia, or else fussing and scolding, like Mrs. Norris. But we also saw that servants are indispensable to the happy-ever-afters of our heroes and heroines.

In Pride & Prejudice, Mrs. Bennet exults in Jane's engagement to Mr. Bingley, with thoughts of the "fine muslins, new carriages, and servants" her daughter will have. Having lots of servants signifies wealth, as owning a Bentley and a Rolex would today. Really, Mrs. Bennet correctly understands the world she lives in. Her only fault is saying the quiet part out loud.

In Mansfield Park, Fanny Price’s parents struggle in cramped, grimy poverty in Portsmouth but they still cling to the veneer of gentility. being waited on by two servants. These servants are, obviously, poorer still.

What if the servants working in the "offices" (kitchen area) at Barton Cottage in Sense & Sensibility could overhear the conversations in the poky little parlour when Marianne and Elinor discuss how much money constitutes a "competence."

"What have wealth or grandeur to do with happiness?" [exclaims the romantic Marianne].

"Grandeur has but little," said Elinor, "but wealth has much to do with it."

"Elinor, for shame!" said Marianne, "money can only give happiness where there is nothing else to give it. Beyond a competence, it can afford no real satisfaction... two thousand a-year is a very moderate income. A family cannot well be maintained on a smaller. I am sure I am not extravagant in my demands. A proper establishment of servants, a carriage, perhaps two, and hunters, cannot be supported on less.”

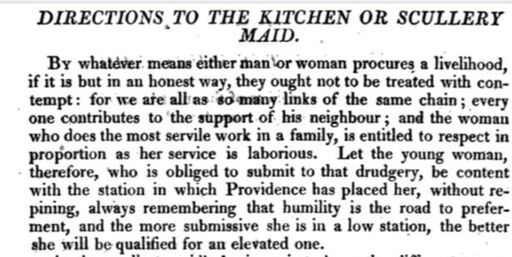

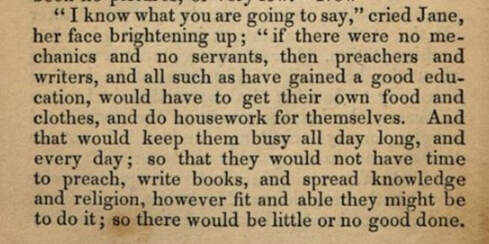

In The Young Servant; or Aunt Sarah and her Nieces, Aunt Sarah prepares her niece Jane for domestic service. She explains that talented people like painters can't make beautiful paintings without the help of servants to prepare the paints. This thought reconciles Jane to her fate:

And if a modern reader scoffs at the idea of being placed in a certain station in life by Providence, consider how many people today actually believe that the position of distant stars determines your personality at your birth.

In the end, there is ample evidence in her letters that Austen cared about the servants in the family but there is nothing in her novels to suggest that she held radical views about social levelling. I get the impression that Austen thought servants needed guidance and some supervision but also deserved respect and consideration. There's no indication that she wanted to do without servants, or thought there was anything amiss in having a gentry class who were waited upon by servants.

Housewife boiling clothes, 1944, Arkansas, Wikimedia Commons

Housewife boiling clothes, 1944, Arkansas, Wikimedia Commons At the same time, the need for servants diminished. The ordinary business of keeping house and keeping yourself and your family fed and clothed took much more work before the Industrial Revolution than it does today. Anna Laetitia Barbould (1743 – 1825) wrote a poem about a typical washing day -- hired laundrywomen come to the house at the break of dawn, the harassed housewife watches the skies, hoping the rain will hold off, and god help the visitor who calls and wants to stay for dinner! The weekly laundry day represented a long day of back-breaking work for the women of the household. In Austen's world, there were no tractors, no threshing machines, no milking machines. In the house, there was no running water, no water heater, no washing machine or refrigerator.

What made the biggest difference in the lives of women? What liberated servants from monotonous toil and drudgery? I nominate electricity. We should look to the changes in daily life brought about by human progress.

| |

| In A Contrary Wind, the first book in my Mansfield Trilogy, we meet Miss Lee, the governess who taught Fanny and the Bertram girls, and learn about the man she loved and lost. Click here for more about my novels. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed