| This post continues my exploration of the literature of Jane Austen's contemporaries. Here's another long 18th century book review, this time for a "novel of fashion." |

The handy thing about a Georgian-era foundling narrative is that you can show the foundling as a plucky and virtuous character struggling to find their way in a society based on birth and rank rather than merit, but, in the Big Reveal of True Parentage, you can explain that the foundling IS actually of good birth! Their good looks, excellent character and intelligence had to come from somewhere, after all.

Are novels about foundlings an attempt to subvert the social order, or does the Big Reveal reinforce the social order? Is this a way of having your cake and eating it too?

Tom Jones, the foundling in Fielding’s 1749 novel, is of illegitimate birth but other foundlings such as Edward Evilen (1796) or Rosalie in the Mystic Cottager of Chamouny (1795) and Edward Montague of A Winter in London all have married parents who have been separated through some combination of bad luck and perfidy. The Big Reveal comes about as a result of amazing coincidence: the lovely Rosalie strums her guitar in the Swiss Alps until the one person in the world she wasn't supposed to meet seeks lodging in her remote cottage. Edward Montagu is raised in a cottage within sight of his true ancestral home. He accidentally meets his father--who wrongly thinks his wife, Edward's mother, was unfaithful to him--while they are both roaming moodily around the neighbourhood...

| “'I-I, your father!' said the stranger, breaking from the arms of Edward, which entwined his knees. 'No—poor wretch! Thou art the fruit of crime, the offspring of adultery! Thou hast no parents; for thy guilty mother and her paramour, thy father, perished in that hour when thou wast rescued from destruction.'” [At this horrible news], "Edward, relinquishing his hold, fell prostrate on the earth… the mysterious stranger, with a wild shriek of despair, smiting his forehead, exclaimed, 'Where, where shall I fly to escape from misery!' and in a moment he was out of sight.” |

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire in costume, by Maria Cosway

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire in costume, by Maria Cosway The title, A Winter in London, does not refer to the gothic-y foundling plot but to a separate and major theme of the novel: the vapid, dissolute world of the London ton in which everybody is absolutely miserable, caught in a vortex of dissipation and consumed with envy of those higher on the social ladder than themselves. The London-based characters are gossiping, quarrelsome, and extravagant, partying at night and sleeping during the day, running up gambling debts, ignoring the bill-collectors pounding on their doors, etc., etc. This genre of novel is called "novel of fashion," or a novel of fashionable life.

Surr’s leading exemplar of this decadent lifestyle is the Duchess of Belgrave, a character said to be based upon Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. The real duchess died not long after the book came out, and some said she was hastened to her grave because of Surr's satirical portrait. Another minor character is a thinly-veiled portrait of successful society physician, Sir Walter Farquhar.

Just as foundlings are both a rebuke and a reinforcement of the class system, so Surr criticizes London society while at the same time providing his readers with enticing descriptions of the lifestyles of the rich and famous. He gives a lengthy description of a lavish masked ball, with “superb” decorations and costumes.

“Passing through this apartment [fitted up to look like a Moorish palace], the visitor next entered a long gallery, which was formed into an Egyptian temple, the effect of which was truly grand and striking…” The branches of the “artificial cypress trees” wave about thanks to “invisible machinery, and thus appeared to be really agitated by the air.”

A pavilion is erected in an indoor garden “built in the rotunda form; the roof was supported by pillars of gold studded with precious stones, around which were entwined wreaths of variegated lamps; from the centre of the dome, which was painted in a masterly style, with the luxuriant representation of every species of oriental fruit, foliage, and flowers, was suspended a superb chandelier, and beneath its trembling splendour, a fountain of curious workmanship played rose-water into golden vases.”

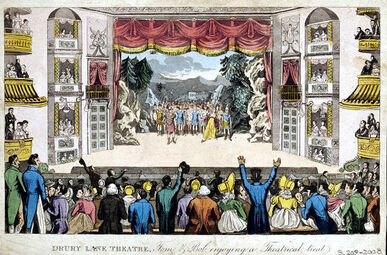

The Duchess of Belgrave attends, dressed as Diana. Our hero Edward looks fetching in tights, and our heroine Emily is a Moorish princess. But as Surr's readers well knew, if you throw a lavish masked ball, you are just asking for trouble. I'll have to do a post in the future about the many plot complications that arise during masked balls.

Alternate view of the prince

Alternate view of the prince The prince is even shown behaving heroically when the inevitable trouble arises at the ball. Signor Belloni, an evil scheming Italian, stalks our hero Edward. The fair heroine Emily pleads for someone to intervene: "I am sure there is danger of some kind!" The prince responds to her plea “with a gallantry that put the rest of the gentlemen to the blush... His example was electric. Every gentlemen was then ready to rush forth after Edward” who, they discover, has been stabbed in the breast by a poniard. It was definitely the Italian, then. Emily loses no time in doing her part: she "utters a loud shriek," and faints dead away. Thus concludes Volume II.

Grub Street, home of aspiring hack writers in London

Grub Street, home of aspiring hack writers in London In addition to the foundling plot and the “London is a sinkhole of vice” theme, the third thread in this novel is eclectic commentary on the social issues of the day. These dialogues are mostly carried on between wise old Dr. Hoare, who is tutor to a feckless young nobleman, and his old friend, Mr. Ogilvy, with Edward sometimes chiming in. For me, this was the most interesting aspect of the novel.

These conversations cover a broad array of issues. but not colonialism or slavery. The story opens with the shipwreck of an East India trading ship, but this is merely a plot device to introduce the shipwrecked foundling, who is brought ashore by a Chinese man who cannot speak English and who promptly dies.

As for slavery, what could be more neutral or oblique than this passive voice passage from Mr. Ogilvy: “unhappily a dispute arose among some of the leading men in power, relative to our colonial settlements in the West Indies. Several pamphlets were published on the occasion. Among others my nephew Charles wrote one in defense of the opinions espoused by his patron, which were also honestly his own.”

The key point in this inserted tale isn't the West Indies; the story is an opportunity for Surr to vent his spleen against book reviewers. Poor Charles is crushed and goes insane when he receives a very personal and sarcastic review. Mr. Ogilvy goes to the editorial office and rebukes the reviewer at length: "No, sir, it was reserved for the present day to bring forth a fry of young critic imps, the mingled spawn of arrogance and envy hatched by mischief, who were to entail disgrace for ever on the word reviewer, by making it synonymous with libeller and assassin.... You may proceed in your career… grin over the collection of hopes destroyed, of fortunes injured, of feelings outraged, of intellects deranged, of hearts broken by your merry malice, or your venomous corruption; enjoy the feast infernal!”"

Dr. Hoare’s friend Mr. Ogilvy criticizes the European custom of having soldiers stationed inside theaters. Better, says Mr. Ogilvy,” that we should be pelted now and then with the rind of an orange, than that our lives should be exposed to the malice or mistake of some hot headed grenadier; --better too that we are occasionally a little incommoded by noise, than that the rude or even riotous jollity of British freedom should be changed to the servile silence or effeminate decency of an enslaved people.”

Female education is also discussed: “I don’t approve of the present system, of making prattling philosophers in petticoats.” [says Mr. Ogilvy] I see no good that is to result to society from having our wives or daughters discharging electric or Galvanic batteries at our heads, or of converting our cookmaids into chemical analysers of smoke and steam.”

“But are not the scientific pursuits of the present day at least as beneficial to society as the old amusements of working carpets and chair bottoms?” doctor Hoare asks, but he is just kidding. He concurs that “it is impossible there should be a difference of opinion” on the subject of females studying the sciences.

Surr is bullish on England and believes it is superior to other countries in terms of social mobility and equality.

“If in one coach you see the family of a duke who have inherited without labour the estates of their ancestors,” Dr. Hoare enthuses, “the very next that follows it will, in all probability, be that of some industrious and fortunate trader, whose splendour, instead of discouraging, animates the spectators, as an emblem of the reward which in this free country is held out, without exception, to the industrious and the enterprising.” (Again, Surr has it both ways when it comes to social mobility. One of the characters is a waiter who works hard, saves money and rises up the world, but he's presented as a sort of scheming, grasping, undereducated skinflint. His son marries the beautiful daughter of a noble family that's fallen on hard times but it's not a love match. There's an ambivalence about the whole thing.)

Surr also counteracts his earlier descriptions of London opulence by having Edward's father, the long-lost duke, inveigh against the heartlessness of the wealthy: “Ah, how many children of misery and woe might the affluent, the skillful, and the powerful rescue from the pallet of disease, the chains of madness, or the debtor’s den, with but a thousandth part of the useless energy wasted in pleasure’s toils!”

The Critical Review noted that A Winter in London was in “great demand” at the “circulating libraries,” but called the story “trite,” and filled with clichés. “The little that is not common-place, is improbable.” As for the editorial commentary, the reviewer notes that the sad tale of the young writer who goes mad when his pamphlet gets a snarky review “is introduced abruptly and without having any connection with the story.”

The Monthly Review said of the gothic plot: “Will the Italians ever revenge, or ever redeem, the stigma which our writers almost constantly throw on them, when an individual of that nation has a part to act in the drama?”

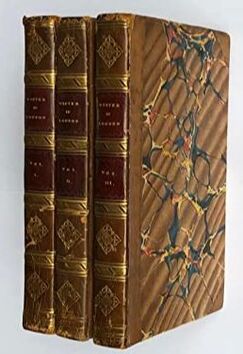

Georgiana, Duchess of Cavendish, by Anne Foldsone Mee

Georgiana, Duchess of Cavendish, by Anne Foldsone Mee While A Winter in London has since fallen into obscurity, one of its characters casts her eye upon posterity. The imitation Duchess of Devonshire character, the Duchess of Belgrave, writes to her sister: “I hope you have carefully preserved the numerous epistles I have written you… it is impossible to estimate how large a fortune they may produce to your posterity in the year of our Lord two thousand and odd… [but] be careful in concealing them at present, lest they should fall into the [wrong] hands before the two hundred years I allude to have rolled over my grave…”

Just as I like dipping into the past, I like to know that Surr was thinking of us, with his "the year of our Lord two thousand and odd."

Previous post: A Guide to Gothic Novels Next post: "The common trash of novels"

The Wiley Online Library says Thomas Skinner Surr (1770–1847) is "perhaps the most famous author of novels of 'fashionable life'." "[H]his work was a touchstone for debates about the moral and cultural worth of novels." That might explain why he inserted all those unrelated debates about the issues of the day; to give his novels additional moral gravitas. In addition to novels, Surr wrote books on the subject of banking. He worked as a clerk in a London bank. His novels sold well but it looks like he kept his day job. His father was a wheelwright and a grocer but his mother was the daughter of a mayor of London, which explains why his name includes his mother's maiden name of "Skinner." However, he never rose to the ranks of the people that he wrote about. The website: UK Red: The Experience of Reading in England, captures remarks from everyday people from 1940 to 1945, culled from their letters and diaries and other records. Here is the entry for A Winter in London Update: When I wrote the above, I had not come across a scholarly article about A Winter in London by Anne H. Stevens which credits Surr with starting a "microgenre" of imitative novels. Stevens, like me, notices that this book is a mixture of different genres but probably owes its popularity to the celebrity gossip. Stevens. (2017). The Season Novel, 1806-1824: A Nineteenth-Century Microgenre. Victoriographies, 7(2), 81–100. https://doi.org/10.3366/vic.2017.0265 Update: More "season" novels reviewed. Links to them at this post for A Winter in Bath. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed