| It's Ann Ryley week at Clutching My Pearls! A new post every day about Ann Ryley (1760-1823), a forgotten novelist, and her novel Fanny Fitz-York, which was not reviewed when it was first published. For more reviews of obscure and forgotten novels, click "Authoresses" and "Books Unreviewed Til Now" at the right. I'm excited to introduce author Ann Ryley to you... |

| |

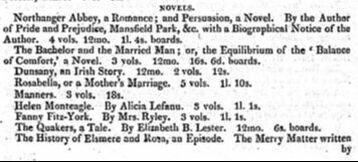

A listing of new novels for 1818 in The Quarterly Review includes Austen's two last novels and Ryley's Fanny Fitz-York

A listing of new novels for 1818 in The Quarterly Review includes Austen's two last novels and Ryley's Fanny Fitz-York Fanny Fitz-York came out in late 1817, the same time as Jane Austen's posthumous novels Northanger Abbey and Persuasion (though all are officially designated as having been published in 1818). Author Ann Ryley was 58 years old when her novel was published, so I've got some kindred feeling for her. I'll share more of her life story later this week.

The Dictionary of National Biography entry for Ann's husband R.W. Ryley described Fanny Fitz-York as a "successful" novel but the only thing approaching to a review or reaction that I've found is a brief paragraph from 1860. Richard Wright Proctor, a literary historian and travel writer, called Fanny Fitz-York “a cleverly-written novel, of considerable interest, especially to women." He added, "though Fanny Fitz-York is now unknown to the majority of readers, who, in their eager pursuit of something new, are apt to overlook the treasures of the past, it still has an abiding place in the circulating library. Here the curious may find this slighted heroine of romance, this forgotten belle of a season, taking her natural rest, half buried in kindred dust, and literally shelved...”

Should we wake Fanny Fitz-York from her slumbers? I think so, given the current academic focus on the social and historical context of novels, as opposed to intrinsic literary merit. Which is not to say Ryley is a mediocre writer; I think she's better than many of her contemporaries. And she holds up much better than her husband, who published five volumes of memoirs clogged with clichés: “A fortnight ago, seated in my cottage, enjoying the height of human felicity—peaceful, domestic, rural comfort—now on my way to the metropolis, preparing to merge into the vortex of public life, and plunge into the troubled sea of dramatic misery!”

Ryley hasn't gotten any attention from scholars but I think she's worth studying because she offers a striking contrast to Jane Austen, for reasons I'll explain.

But first, a bit about the story itself...

The opening reminds us that people of this era were used to high infant mortality rates and could read a sentence like this without blinking: “Mr. Fitz-York married Lady Ann Grosvenor under the fairest auspices; and for several years, during which period they had six children, though only one daughter survived, no couple could be found whose happiness surpassed theirs.”

But alas, Lady Anne, mother of our heroine, loses her husband and her beloved brother Frederick in a boating accident. At the reading of their wills we learn that the late lamented Frederick has a natural son, about ten years old, but nobody knows where the mother and son are.

The late Mr. Fitz-York didn't want his only daughter to be the prey of fortune hunters, so it's given out that she has only a 5,000 pound inheritance.

So after all the introductory deaths, we’re left with one desolate widow and her little daughter living in a gloomy tower. In the adjoining village we have a widowed curate, his "old maid" sister-in-law, and his twin babies. There's also Henry Tudor, a nice young man living with the curate for a private education, just as Edward Ferrars was privately educated in Sense & Sensibility.

Young girl and her governess, Jean-François Portaels

Young girl and her governess, Jean-François Portaels Lady Anne has some relatives who have managed to not die, but they are snobby aristocrats. We’ll meet them later. First, the childhood of Fanny, which gives the author a chance to expound on educational theories for children. (As we have seen, this is a huge topic in novels of the day, especially as regards the consequences of a good or bad education on the future conduct of the characters). The lovely Rosette, sister to the curate, is hired as Fanny’s governess so Fanny can have a youthful companion in her isolation.

Sweet and artless little Fanny is not allowed to receive “bribes” for good behaviour, only “rewards.” Her favourite rewards are reading the bible and making clothes for the poor children of the village. I might mention at this point that the author Ann Ryley never had children and there’s no indication in her life story that she ever met any children. But to continue.

The story expands out to some of the other inhabitants of the quiet village. The Gaskell family consists of a gossiping Greek chorus of mother, two silly daughters and a wastrel son, living with a very disappointed Mr. Gaskell. Mrs. Gaskell is a narrow-minded, vulgar woman who doesn’t understand what her embittered husband says. Like the Bennets in Pride & Prejudice, there is no meeting of minds. The three Gaskell offspring are used in the novel as examples of ignorance, selfishness, and vulgarity. Their stories serve as a contrast to the amiable Fanny and her friend/governess Rosette.

Anyway, before long Fanny is 16, old enough to see something of the world and commence her adventures as a heroine. Ryley playfully indicates to her readers that she cannot bring herself to obey novelistic conventions with asides such as: “unlike many heroines, our Fanny was sometimes hungry," and "the amiable timidity,—the overwhelming modesty, —and excessive pusillanimity, of some heroines, may throw ours into the shade. Be that as it may, we are incapable of altering her…”

Lady Ann, Fanny, and Rosette set out for a tour of seaside attractions with a family friend, an older man named Mr. Strictland. They visit Lyme Regis and attend a public ball, giving the reader a picture of Lyme Regis as it was when Jane Austen visited with her family. The novel is set in 1812, the same year that pioneering paleontologist Mary Anning dug up an ichthyosaur skull, but there is no mention of fossils, just those flint-hearted noble relatives. The relatives keep Lady Anne and Fanny at arm’s length because they erroneously suppose that Fanny is poor and they don’t want her to catch the eye of her cousin Lord Moseley. But during their travels, Lady Anne’s carriage breaks down and a handsome gentleman offers them his own carriage to get out of the rain. He calls himself ‘Moseley.’ He pretty much joins Lady Anne’s party, travelling along the coast with them.

Flawless disguise

Flawless disguise In the silliest contrivance of the plot, it turns out that 'Moseley" is indeed Lord Moseley, who courts Fanny while wearing a wig and calling himself just Moseley. Everyone remarks on the amazing resemblance between this Moseley guy and Lord Moseley, but nobody says, “what do you mean? that’s just Lord Moseley wearing a wig.” Also, I don’t think a cautious prudent widow like Lady Ann would let some complete stranger, no matter how gentlemanly, hang around her daughter unless he could provide some personal references. Were we, the readers, supposed to be hoodwinked as well, or were we supposed to wonder if 'Moseley' is really Fanny's cousin, the missing illegitimate son of the late Frederick? Or is it all a tongue-in-cheek joke?

In addition to Lord Moseley, we've got other possible contenders (not counting the villain, whom we'll meet later) for Fanny’s hand. In Volume I there’s her childhood friend Henry Tudor; more suitors pop up after Fanny gets to London.

Regency-era Court Dress

Regency-era Court Dress Lady Ann is astonished and vexed when a false marriage report is printed in the newspaper, announcing Fanny’s engagement to Lord Moseley. “To have [her daughter’s] name bandied about in the public prints, was a matter so repellant to her native delicacy, and to every sense of propriety, that she would have shrunk from the exposure, even had the statement been correct…”

The snobby relatives are likewise vexed and accuse Lady Ann of having spread the rumour. Lady Ann is so annoyed that she tells them that there is no way she would allow Fanny to marry Lord Moseley because of the rude and shabby way they’ve always treated her, and they would no doubt treat Fanny badly as well.

When Fanny attends her debut at St. James’ Court, Lord Moseley shows up and makes a scene. “Fanny, you have undone me! You, and your dear mistaken parent have driven me to the edge of the precipice, and this interview decides my fate as far as respects the present world.”

If I were a beautiful young heroine making my bow to the Queen at St. James’s Court I wouldn’t be impressed by a hero who drags me into a private corridor (thus compromising my reputation) to threaten he’s going to kill himself, then gets into a physical altercation with another admirer—whose bloody nose spatters on my court dress—then challenges him to a duel so now I have to worry about them killing each other. Not to mention that bizarre business about wearing a wig and lying about it for weeks.

I think Austen would have made more of the entire Lord Moseley sub-plot; there would have been some moral lesson behind building up a potential hero and then taking him off the chess board, which I can't discern in this novel. I don't think Fanny learns anything from this experience. She is already a "picture of perfection" heroine and has nothing to learn.

Next up: What happens when a girl from good family loses her virtue? Why yes, she dies of course, everyone knows that. But Ann Ryley had other ideas...

"Can we talk?" "Can we talk?" We can't mention debuts at the court of St. James without mentioning how ridiculous hoops look under a high-waisted Regency-style dress. Ann Ryley thought the same: "of all the unnatural deformities which the caprice of fashion has at various times invented, the whalebone petticoat is the most unwieldly, the least easily managed, and grace is no longer grace, so encumbered…” Of her heroine, Ryley spares herself the effort of a detailed description: “I dare say my youthful female readers will think me unpardonably deficient if I omit the description of our heroine’s dress on this grand occasion. I once hoped the newspapers would have anticipated me, but guess my mortification, when the one I daily take was served up with my breakfast, to find no mention whatever made of Miss Fitz-York. I waded twice through the monotonous description of court costume, and court presentations, without finding my favourite Fanny’s person, dress, or behaviour noticed; although the former and the latter were, according to my old-fashioned judgement, unrivalled that day at St. James’s…. A fire in the palace of St. James in 1809 put an end to court levees for a while. Ann Ryley mentions that "there had been no public Court for a considerable length of time" when her heroine made her appearance. I used the 1809 fire in my novel, A Contrary Wind, to disappoint the hopes of the Bertram girls, who are unable to make their curtsey to the queen. Ryley's reference to "the amiable timidity,--the overwhelming modesty, —and excessive pusillanimity, of some heroines" signals to us that yes, Fanny Price's timidity was supposed to be endearing and "amiable" to contemporary readers, however it lands with modern readers. It also tell us that the modest, timid heroine was so common as to be a literary trope. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed