| This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws some occasional shade at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. |

Shocker!

Shocker! In the previous post I discussed the possibility, floated by Austen expert Robert Morrison, that Marianne Dashwood was hiding a secret pregnancy in Sense and Sensibility. After a careful re-read of the novel, I've concluded that making Marianne pregnant contradicts the central preoccupation of the main characters as reiterated throughout the conclusion of the novel. To explain what I mean, let's start by recapping the set-up for the dramatic scene when Willoughby arrives at Cleveland, the country estate of Mrs. Jenning's daughter, late at night.

Marianne Dashwood fell seriously ill at Cleveland on her return trip from London. Her hosts, Mr. and Mrs. Palmer, leave the house so their baby does not catch Marianne's infection. Their other house guest, Colonel Brandon, hurries off in his carriage to fetch Marianne's mother. That leaves Elinor, Mrs. Jennings, and the servants.

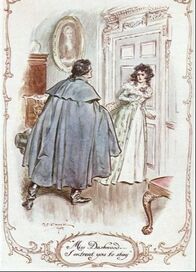

Marianne is feverish and delirious, but fortunately she pulls through and falls into a restful sleep. Once she is pronounced out of danger by the apothecary, Mrs. Jennings goes to her own room "to write letters and sleep." Elinor is too happy to sleep, so she is sitting by Marianne's bedside when she hears a carriage arrive. She summons Betsy, Mrs. Jenning's maid, to stay with Marianne and she goes downstairs. To her shock, it's Willoughby, the cad who jilted her sister. He explains he came to Cleveland to persuade Marianne and Elinor to hate him "one degree less" than they surely must "do now." He exclaims: "Tell me honestly... do you think me most a knave or a fool?”

Who cares if Willoughby had the opportunity to rehabilitate his character? Who cares if we “hate [him] one degree less than [we] do now”? I know I wouldn't have given him the patient hearing that Elinor did, so I didn't miss the absence of this scene in the 1995 movie. However, as I carefully re-listened to the book, I finally get what Willoughby was driving at...

Gratitude

Gratitude If Marianne was indeed dying at Cleveland of putrid fever, as Sir John Middleton had informed him, Willoughby was concerned that Marianne would pass away hating him with her last breath. Elinor reassures Willoughby that Marianne is hopefully "out of danger" (but note she does not add, "She just had your child," or "she just miscarried your child.")

Willoughby exclaims, "What I felt on hearing that your sister was dying, and dying too, believing me the greatest villain upon earth, scorning, hating me in her latest moments—for how could I tell what horrid projects might not have been imputed? One person I was sure would represent me as capable of anything."

In other words he has been imagining that Marianne thinks he's a heartless cad who never loved her, who only had the "horrid project" of seducing her. He's been thinking, what have all of you assumed about me? What has Colonel Brandon been telling you?

Yes, he admits, he wasn't serious when he first met Marianne, and was only amusing himself by flirting with her, but soon he did fall in love. He was on the point of proposing when his aunt Mrs. Smith learned that he seduced and abandoned Eliza Williams. Cast adrift without his inheritance, he chose money over love. After rushing down the aisle with an heiress, once again financially secure, he is free to regret the love he lost. He might have been a "knave" where Eliza was concerned, but she was of a lower social class anyway, and she didn't deserve his respect because she was willing to be seduced. But now, where Marianne was concerned, Willoughby now thinks himself a "fool" to for placing money ahead of love.

Is this distinction important? It appears to matter a great deal to Austen, otherwise she wouldn’t have given us that whole Willoughby-at-Cleveland scene. The first thing that Elinor pondered when Willoughby publicly jilted Marianne in London was the question of his true intentions. She noticed his air of "embarrassment which seemed to speak a consciousness of his own misconduct, and prevented her from believing him so unprincipled as to have been sporting with the affections of her sister from the first, without any design that would bear investigation." Just as with Willoughby's term "horrid project," Elinor's reference to a "design" is a delicately stated way of referring to seduction, sex outside of marriage.

The distinction between unprincipled cad and fickle suitor is also very important to Marianne, and it is the "one point" she dwells upon. Just what were his intentions toward her? She tells Elinor:

| "At present, if I could be satisfied on one point, if I could be allowed to think that he was not always acting a part, not always deceiving me; but above all, if I could be assured that he never was so very wicked as my fears have sometimes fancied him, since the story of that unfortunate girl—” She stopt. Elinor joyfully treasured her words as she answered,“If you could be assured of that, you think you should be easy.” “Yes. My peace of mind is doubly involved in it; for not only is it horrible to suspect a person, who has been what he has been to me, of such designs, but what must it make me appear to myself? What in a situation like mine, but a most shamefully unguarded affection could expose me to—” “How then,” asked her sister, “would you account for his behaviour?” “I would suppose him,—Oh, how gladly would I suppose him, only fickle, very, very fickle.” |

Marianne describes herself as someone who came close to danger, but did not fall. She is horrified to realize how easily, how eagerly, she placed herself in a vulnerable position. “[W]hat must it make me appear to myself? What in a situation like mine, but a most shamefully unguarded affection could expose me to—” She breaks off here, because it would be indelicate to be more specific.

Elinor then judges the time is right to tell her about Willoughby's visit to Cleveland. She assures her that Willoughby loved her and did not regard her as another disposable Eliza Williams. This brings Marianne some comfort. She asks Elinor to tell their mother as well.

Mrs. Dashwood, likewise, does not regard Willoughby as the seducer, or even the attempted seducer, of her daughter. She condemns him for the seduction of Eliza. She concludes: "Nothing could restore him with a faith unbroken—a character unblemished, to Marianne. Nothing could do away the knowledge of what the latter had suffered through his means, nor remove the guilt of his conduct towards Eliza."

Remorse

Remorse As soon as she can bring herself to speak of it, Marianne assures her mother and Elinor “I never could have been happy with him, after knowing, as sooner or later I must have known, all this." Again, it's too painful and indelicate to spell out what "all this" even means, but she does say she's lost all respect for Willoughby. "I should have had no confidence, no esteem. Nothing could have done it away to my feelings.” Is she speaking of mere jealousy, of learning that Willoughby had a lover before her? I don’t think so, because Mrs. Dashwood understands she is speaking of Willoughby’s conduct: “I know it—I know it,” cried her mother. “Happy with a man of libertine practices!—”

Elinor moves on to talk about Willoughby’s selfishness and extravagance, then she returns to the subject of his immorality: “all Willoughby’s difficulties have arisen from the first offence against virtue, in his behaviour to Eliza Williams. That crime has been the origin of every lesser one, and of all his present discontents.” If Elinor had known of Marianne's secret pregnancy, she's putting on quite a performance for her mother here, She would be referring to the seduction of her own sister as a "lesser" crime.

We're told “Marianne assented most feelingly to the remark.” So here she is either agreeing that Willoughby’s seduction of Eliza was the worst crime Willoughby committed, or she is lying and hiding her own guilty secret.

All of the dialogue and passages I've quoted reiterate, again and again, that Willoughby's intentions were honorable until he threw Marianne over for money. None of these statements make any sense if Marianne became Willoughby's lover.

Gallant but stern attitudes

Gallant but stern attitudes Brandon is very sorry for Eliza but he regards her as partly responsible for her predicament because of her "misconduct." Recollect how strongly Colonel Brandon felt about the fall of Eliza's mother, his own Eliza, his lost love. He was so horrified by her behavior that her death was a release in his eyes. Death is to be preferred to dishonor, folks.

Had Marianne surrendered her virtue, she, just like Eliza Jr., would also have been in a “wretched and hopeless” predicament “with a mind tormented by self-reproach, which must attend her through life.” At least in Brandon's eyes.

Would a man like Colonel Brandon marry a fallen woman, knowing her to be fallen? If he knew that Marianne had become Willoughby's lover and carried his child, would it make a difference to him? I believe he'd never marry such a woman. But I like to imagine a happier ending for Eliza Jr.. Brandon hides her away, to await the birth of her child, after which she is supposed to spend a lifetime being tortured with remorse. But perhaps some widower with children might take her on, especially if Brandon ponies up a good dowry. Perhaps she will meet another Robert Martin, (the intelligent yeoman farmer from Emma.)

My earlier defense of Colonel Brandon is here.

So Austen emphasizes, repeatedly, that Willoughby's intentions toward Marianne were honorable; he wasn't trying to seduce and abandon her. It's just that he was too weak to economize until he could marry Marianne. As Mrs. Jennings suggests: "Why don’t he, in such a case, sell his horses, let his house, turn off his servants, and make a thorough reform at once? I warrant you, Miss Marianne would have been ready to wait till matters came round."

I suspect this distinction doesn't have the moral or emotional weight today, that it would have had in Austen's time. Yes, young women get upset today when they are wooed and then "ghosted" by a man, as with the case of "West Elm Caleb," who is apparently a young man-about-town who likes to toy with women's affections. But even so, there is no societal expectation in the modern Western world that a man who beds a girl must make an "honest woman" of her by marrying her, as we used to say. As Ben Sexsmith said of "West Elm Caleb": "these are not the 1800s, for better or worse. Welcome to dating in the twenty-first century, ladies. Caleb sounds like a cad but if you want casual dating, don’t be too surprised when people treat you casually as well."

In Austen's time, a respectable girl of the gentry class having sex outside of marriage paid a horrible penalty for it, and that penalty might include being dragged to the altar and forced to marry a man she didn't want to marry. People in Austen's time and of her class took the issue of female chastity so seriously that it was the centerpiece of many novels. It's why the best and most desirable possible outcome for Lydia Bennet was for her to marry a wastrel like Wickham. That's why it makes no sense to include a secret pregnancy as a hidden sub-plot with no consequences in Sense and Sensibility.

It’s a different world now. For the first time since official national record began to be kept, more children were born out of wedlock than in last year in England (2022).

For more discussions of unfounded theories, see here and here.

Scholar Ellen Moody mentions that author Charlotte Smith (1749-1806) "has numbers of women [characters] who have children out of wedlock who are partial heroines; she was attacked for giving some of them happy endings." I will mention any other examples I come across of 18th century female characters who escape with their lives after straying from the paths of virtue. Novels written in the first half of the 18th century often had more risqué plots than novels written in Austen's time.

Eliza Jr. has been made the main character in Austen fan fiction, notably by Joan Aiken. A review of "Eliza's Daughter" is here.

Previous post: Was Marianne pregnant? Next post: Conversational advice from Mrs. Elton

RSS Feed

RSS Feed