| Note: Last year, I shared a provocative article by noted Austen scholar Lila Proof, which referenced the pioneering work of Dr. Aprille Stulti. To my surprise and gratification, I was subsequently contacted by Dr. Stulti and asked if I would help publicize her exciting research discovery concerning Mansfield Park. Take it away, Dr. Stulti... |

the hermeneutics of the cross and the chain in Mansfield Park

A special guest editorial by Aprille Stulti, Ph.D.

This essay will contend that a close reading of language in Mansfield Park—especially of such seemingly innocuous words such as “survey” and “yield”—reveals Austen’s counter-reaction to agricultural development. Mary Crawford is not merely trying to hire a horse, she is protesting the encroachment of capitalist-based agriculture, which ironically supports the prosperity of her own gentry class. Mary is paradoxically presented as both victim and beneficiary--and finally perpetrator--of imperialist violence.

This essay will explore how key scenes in Mansfield Park, especially those concerning the amber cross and chain, might adumbrate Austen's resistance to her times...

William Leybourn's "The Compleat Surveyor" 1722

William Leybourn's "The Compleat Surveyor" 1722 Fanny Price, the heroine/hostage of the novel, is associated with surveying immediately upon her arrival at Mansfield Park; we are told that the young Bertram sisters, Maria and Julia, “were soon able to take a full survey of her face and her frock in easy indifference.”

A “survey” of Fanny inevitably associates this vulnerable girl in the readers' mind with the imposition of invisible boundaries on open space. The language that describes Fanny's "yielding" is the language of land surveying, cultivation and conquest. It is not insignificant that farmers spoke of “breaking” the land with a plow. Fanny, too, will be cultivated, transformed into a genteel young lady. She is forced to yield to the will of others, just as farmland yields crops: Repeatedly we are told Fanny is "obliged to yield," or "she must yield."

From this introductory chapter, until we come to the Sotherton episode, the references to surveying and improvement are few. However, the more obliquely Austen refers to surveying, the more important it is to our understanding of the novel. Within that negative space created by Austen, the idea of the imposition of control is pointedly invoked by the name of Dr. Grant, the resident clergyman of Mansfield, and the host to Mary Crawford and her brother Henry. Dr. Grant's name is highly suggestive of grants of land, as from a sovereign to a loyal subject. The Grants, significantly, also busy themselves in extending and improving their property. They have “carried on the garden wall, and made the plantation to shut out the churchyard.” This last comment comes from Mrs. Norris, who is "excessively fond" of "planting and improving."

Surveying returns “as the particular object” when the young people go to Sotherton. “How would Mr. Crawford like, in what manner would he chuse, to take a survey of the grounds?" As the print from "The Compleat Surveyor" (above) indicates, surveying was presented as a benign activity carried out by little cherubs, but Austen deploys Henry's survey of the grounds ironically as a powerful metaphor of the tyranny of land ownership.

Of all of the characters, Henry Crawford is most associated with surveying.And before long, Henry's predatory gaze falls upon Fanny.

Austen's sailor brother Charles gave crosses to Jane and Cassandra

Austen's sailor brother Charles gave crosses to Jane and Cassandra "He loves to be doing," his sister says proudly (and suggestively) of her brother's fondness for "improvements." The oppressive heteronormativity and patriarchy of Henry Crawford’s flirtatious games are intertextually allied to surveying and land use through the material objects of the cross and chain in Chapter 26 of Mansfield Park.

The cross and chain were taken at face value by previous generations of Austen scholars; the amber cross was a symbol of the faith practiced by Fanny Price and her creator, and is especially valued by Fanny as a gift from her beloved brother William. The chain is from Edmund, the man she secretly loves, and it enables her to wear the cross. Austen tells us that Edmund’s chain and cross together are “memorials of the two most beloved of [Fanny’s] heart, those dearest tokens so formed for each other by everything real and imaginary.”

But of course, Austen's intent here is ironic. This truth has been acknowledged in post-colonial Austen scholarship for over thirty years: no-one today supposes that Mansfield Park is a love story, that Fanny could possibly love Edmund, or be proud of her colonizing brother William the sailor.

It is agreed that Austen is subverting something with the cross and chain, but opinions still differ as to exactly what she is subverting. One scholar has argued that the chain represents slavery, and the cross represents the Church of England’s complicity in slavery through its ownership of the Codrington plantations. Others have seen a straightforward sexual inference. Henry Crawford’s ornate necklace “would by no means go through the ring of the cross… it was too large for the purpose.” Edmund’s (presumably smaller) “chain” does fit through. It goes without saying that any object that is longer than it is wide is an encoded sexual symbol, but I intend to extend and contest the existing interpretations.

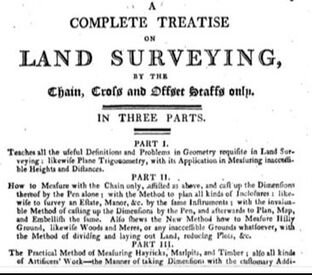

In fact, the chain and the cross together are the tools of the land surveyor, as Austen’s contemporaries would have instantly recognized. In encountering Mansfield Park, they would undertand the remarkable similarities with A Complete Treatise on Land Surveying, by the Chain, Cross and Offset Staffs Only (1798), parallels that critics have not previously noted.

The Treatise is described by the Dictionary of National Biography as a “a popular work which went through five editions by 1813,” which means it preceded, was better known, and was more widely-read than Mansfield Park (published in 1814.)

Space permits only a few examples of the intertextual relations between Mansfield Park and the Treatise. The Treatise states (emphasis added): “Suffer your chain leader to go no farther than the nearer side of the ditch... the ditch being the property of the next field.” Paradoxically, Austen camouflages the allusion by never using the word “ditch” in Mansfield Park; she substitutes the word “ha ha.” This interior joke must have afforded much grim and ironic amusement.

“Suffer” in this sense means “to permit or allow.”* Edmund, significantly, uses this same word in the scene at the chapel at Sotherton when he ostensibly defends public worship over private prayer: “Do you think the minds which are suffered, which are indulged in wanderings in a chapel, would be more collected in a closet?” Edmund wants anyone capable of independent thought to be "collected," preferably in a place where he can keep an eye on them. Even this chilling pronouncement does not shake Fanny’s misguided loyalty to Edmund.

We move from this unsettling scene to one even more distressing: Edmund argues with Mary Crawford as they walk in the wilderness. And what topic, out of all the topics in the world, are they arguing about? The extent of the wilderness! They have both visually surveyed the wilderness, an artificial simulacrum of unimproved land, and disagree about its extent. Mary says “with feminine lawlessness” that the unconquered area is vast, while Edmund “attacks” her and attempts to “dictate” to her, to force her to acknowledge that the remaining uncultivated land “could not have been more than a furlong in length.”

“Oh! I know nothing of your furlongs,” Mary protests, but before long, she herself becomes complicit when she places Henry's necklace, or rather, his chain, around Fanny's "lovely throat" and waves away Fanny's feeble resistance. Thus, Austen inexorably subverts and intertwines the themes of imperialism and resistance; of conqueror and conquered.

The word "survey" is pointedly used by Austen again in the Portsmouth scenes, but only after Henry Crawford has arrived there. Henry and Fanny are walking around the docks from which England's imperialist fleet sailed: "they were very soon joined by a brother lounger of Mr. Price’s, who was come to take his daily survey of how things went on." And of course the imperialist forces "went on" to the four corners of the earth, with Fanny as supine witness. But she is more than a mere witness at Mansfield, that is to say, Man's field, where everything and everyone is brought under patriarchal dominion.

We must inevitably see Fanny as complicit

We must inevitably see Fanny as complicit One by one, the characters of Mansfield Park fall in line with the agenda of capitalist-based agriculture and imperial exploitation. Austen adds a further layer of bleak irony when she presents Fanny, in chapter 16, becoming a colonizer herself as the colonizer of the East Room: (emphasis added) “[Fanny] had added to her possessions, and spent more of her time there; and having nothing to oppose her, had so naturally and so artlessly worked herself into it, that it was now generally admitted to be hers. The East room, as it had been called ever since Maria Bertram was sixteen, was now considered Fanny’s, almost as decidedly as the white attic.”

It is in the East Room that Edmund surprises Fanny with the gift of “a plain gold chain, perfectly simple and neat” as from one surveying conqueror to another. She is stunned into almost open revolt by the symbolic associations of such a “gift.” She stammers, “I cannot attempt to thank you… thanks are out of the question. I feel much more than I can possibly express.”

But this is the last flicker of resistance. Fanny Price embraces the values of Mansfield Park at the price of her independence, even at the price of her voice. From the middle of Chapter 46 to the end of the novel--11,560 words--Fanny speaks only three times. Some people speak to her, we are told by the narrator that Fanny answers: (“believing herself required to speak”) but we seldom hear Fanny’s own words. She is groomed to silence, acquiescence and complicity.

The ending of Mansfield Park is unparalleled for its concluding irony, in which Austen can be properly understood as meaning the opposite of the actual words on the page. By giving Mansfield Park such an inarticulate and silenced "heroine," Austen shows us that the narrative force of the novel derives from that which cannot be said.

William Davis (1771-1807), author of The Treatise William Davis (1771-1807), author of The Treatise *I would never suggest that a writer of Austen’s subtlety cannot intend more than one meaning, as in the word "suffer." Prior scholarship has established that the “Moor Park” apricot tree--of which Mrs. Norris is so proud--refers not merely to a well-known English estate called "Moor Park,” named after an adjoining moorland, but is an undeniable signifier of the slave trade, because Shakespeare’s Othello was a Moor. Thus apricots are a stark reminder of chattel slavery. But in addition, the reference to “moors” weaves Mansfield Park together with the Treatise, with its references to "inclosure" and "improvement": “if moors, marshes, bogs, heaths, shallows, pools of water, shrubs or rocks, belong to and adjoin the estate, measure what is improvable first; and if any of the rejected part will admit of improvements, measure and return it as such; the remainder should appear in your map as unprofitable ground.” The assonance between “moor” and “more” ratifies the connection between agriculture and imperialism. "Moors” are not always "improvable," and if not improvable, are "unprofitable." We instinctively recoil from the capitalism of "profit." |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed