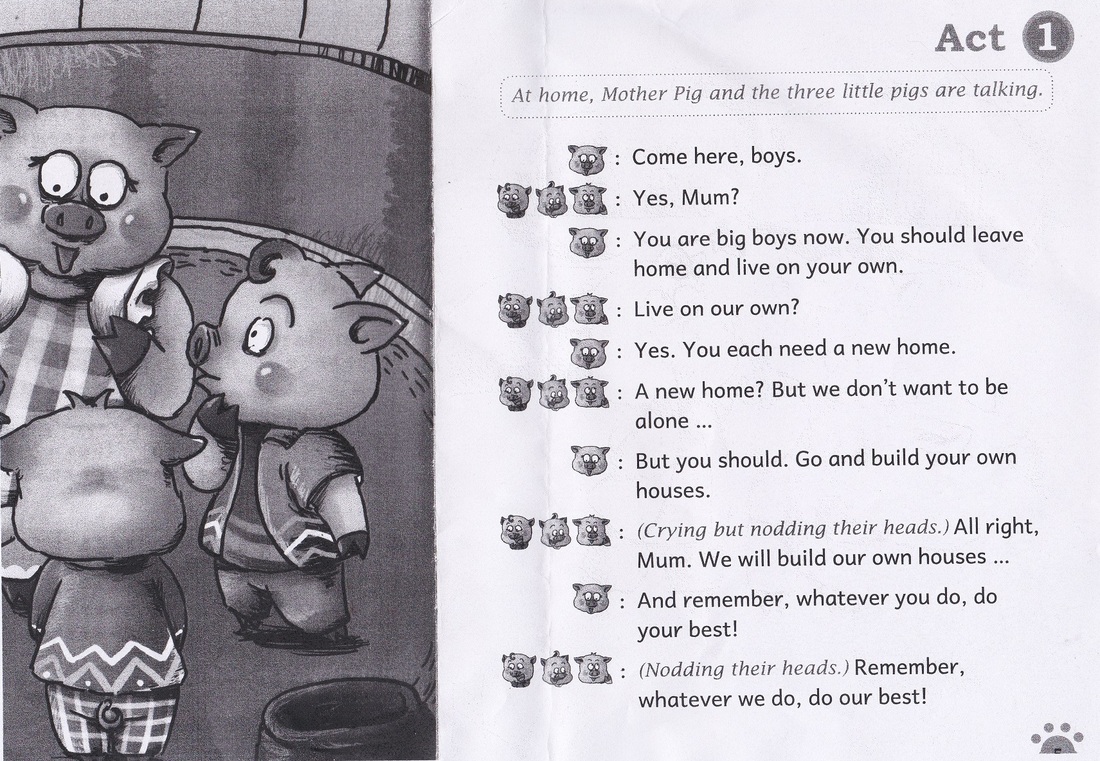

But in the Chinese version, the three little pigs react as any properly filial little pig would, and the writer is at a loss to provide a rationale or plot-driven reason why the little pigs should leave their mother. She just says, "But you should."

This Chinese reaction to the Little Pigs fable really brought home to me the central importance of family and filial piety in their culture.

Lucy Isabella Bird, a Victorian-era explorer and journalist, visited a Chinese school when barging up the Yangtze and explained the tales to her readers as "quaint and delightful stories of filial devotion. This is a most popular collection of tales, and the examples embroidered on satin, or painted on silk, or coarsely daubed on paper, are to be seen everywhere."

Our own Chinese friend may have found the stories quaint, but she didn't always think them delightful, judging by the occasional snorts of derision that accompanied her translations of the little plaques that were mounted next to every tableaux. Mostly they are tales of adult children who will go to any lengths to please or care for their aged parents. When we got to the story about the man who buried his child alive because he had no food and he chose to save what remained for his mother, we all quailed a bit. (In the version on the Wikipedia page, the man is rewarded better than Abraham. While digging the hole to bury his child, he strikes a cache of gold coins. Happy ending.)

A little more on what Lucy Isabella Bird had to say, because nowadays it is common to portray 19th-century English explorers and missionaries as purblind cultural hegemonists. After her school visit, Bird wrote: It is easy to laugh at an education which for boys of all ranks consists solely in the knowledge of the ancient Chinese classics, and there is no doubt that it stunts individuality, belittles genius, fosters conceit, and produces incredible grooviness.*

But she adds: it is essential for us to see quite clearly that our Western ideas find themselves confronted, not with barbarism or with debased theories of morals, but with an elaborate and antique civilisation which yet is not decayed, and which, though imperfect, has many claims to our respect and even admiration.... Deficiencies there are, but there is not a single thing in this curriculum which a man ought not to be the better for learning, or one thing which it would be desirable for him to forget.

However, during our visit Ross took a picture of a lotus flower of which he is justly proud. Isn't that lovely? The temple complex is built on a hillside on several levels and there were some little raised ponds and fountains, some with water lilies.

The small temple at the highest level had the usual large wooden idoIs but also a nice winding staircase up to a lookout on the second floor. Well, it would have been a lookout if the windows weren't ornamented and the day weren't so smoggy.

I find the painted ceilings of the temples a lot more attractive than the big wooden idols.

I was grateful to have toured the temple complex, not just for the beauty and the exercise, but because now I can decode more of what I see around me.

We've gone down this corridor at the train station to get to the train platform several times. Now, I recognize the pictures on the ceiling as being illustrations of the twenty-four filial tales. So now instead of just seeing some Chinese pictures as I tootle along with my suitcase, I can comprehend that they illustrate stories that Chinese people have been reading since before Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue.

By the way....

When this is published, Ross and I will be in Shanghai, wrapping up a two week visit with our oldest son Gus, a grown man who is spending his entire vacation with his parents in China. There's filial devotion for you.

Bird, Isabella Lucy The Yangtze Valley and Beyond: An Account of Journeys in China, Chiefly in the Province of Sze Chuan and Among the Man-tze of the Somo Territory Kindle Edition.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed