| Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. I’ve also been blogging about now-obscure authors of the long 18th century. For more, click "Authoresses" on the menu at right. Click here for the first in the series. |

Our story begins with a female voice pleading for help, heard outside the humble cottage of Gabriel and Mary Feller. Mary used to be a servant in a posh household, and the daughter of that household was seduced by one Captain Berringer. She flees to Mary to hide her shame and to go insane after she delivers an infant boy. She then drowns herself in the river.

Baby William is passed off by Gabriel and Mary as their nephew, but strangely, the mother gave him the surname of her seducer, who, everyone agrees, is a loathsome reptile. The rest of volume One is taken up with William’s boyhood, and meeting the girl he marries…

"Men of war" cariacture, 1791, detail

"Men of war" cariacture, 1791, detail William grows up on brotherly terms with the Feller’s boy Robert, and their country childhood is pretty idyllic. In one interlude, Robert visits a nearby town on market day. It’s common in novels of this era for the “good” characters to dislike the glitter and vice of London. In this story, Robert is repulsed by what he sees in an average market town; London would probably finish him off completely. He saw a public execution, and a starving woman whipped for stealing some mutton. Furthermore, “[a] lame beggar, to whom I had given a penny, stole my handkerchief out of my pocket….at a little distance, a fine-drest lady was drinking gin and eating gingerbread with a black trumpeter. I then said to myself, if this be seeing the world, I hope I shall never leave my home again.”

William is a discerning young boy who saw that the village clergyman was a hypocrite and a cold fish who preached charity but didn't help the poor in his parish. This clergyman dies, and his successor, Rev. Lackington, takes notice of William. The young lad spends a lot of time at the rectory with Rev. Lackington. In a modern novel, this could mean only one thing, but in 1804, it means that Lackington wants a son and heir. Sadly, Lackington doesn’t update his will in time, and his intention of buying a farm for William falls through. The good news is that Lackington’s beneficiary, Lady Augusta, is well off in her own right and despite her faults of character, is willing to do something to help William. She offers to buy him a commission in the army or find him a job as somebody’s secretary. William chooses the army. The author set us up for this choice by telling us that William, although very bright, is not really academically minded. At any rate, William has also acquired a lovely bride, Lorina, the daughter of a reduced gentlewoman who has come to live in the village. The young people get married on little more than hope and great expectations.

That’s pretty much the entire first volume of the novel. The author has introduced most, but not all, of our main characters and gotten them all arranged and organized. No hint of a looming crisis, no depiction of faults or unfulfilled wishes in the bosoms of our main characters. No inciting event in sight.

Bing AI image

Bing AI image On the voyage back, William nurses an older soldier who is consumed with guilt and anguish and it turns out to be—you'll never guess—go ahead, guess—you guessed it—his own father, serving under an assumed name. Apart from giving us a portrait of the wages of sin, Summersett does not use the reappearance of the father as a plot-changer. Perhaps it’s intended to show our main character hardening in his attitudes against immoral behaviour. As a dutiful son, William prevents dad’s body from being heaved overboard; he brings him to England and buries him. We still haven’t had our inciting event.

The inciting event is this: The beautiful Lorina attracts the attention of one of William’s brother officers, a Captain Russel, who mounts an extended campaign to persuade Lorina that he is dying for love of her and further, that her husband William is carrying on a secret affair with Lady Augusta.

Lady Augusta is a sort of Mary Crawford-like character, and the most interesting person in the book, though we see very little of her. She confides a shocking secret: when she lived in Italy, ( before her recent marriage) she gave birth to an illegitimate child! By an Italian!

I suppose William’s gratitude to his benefactress keeps him from stalking out of the room then and there. But he respects her and promises to keep her secret. She tells William she is planning to separate from her husband. William, shocked, urges her to try to reconcile with her husband before resorting to anything so drastic. She pleads:

| “Would you believe Heyland to be capable of brute violence—of savageness, which is to be found only in those whom men should be ashamed to call men? Gay, hypocritical villain! Look at this arm!—” “Good God!” –It is black with bruises—who did this mischief to you?” “Heyland. He dragged me on the floor—griped, beat me. He could not have more abused the vilest strumpet of the town.” “She drew up the sleeve of her morning dress, and exposed her injuries. The heart of Berrington was full of pity and indignation; and scarcely knowing what he did, he… pressed his lips on the bruised and discoloured flesh. At that moment Lorina entered….” |

Deceived with a forged letter. Bing Image AI

Deceived with a forged letter. Bing Image AI Lorina knows that there is something going on between Lady Augusta and her husband, but William is not free to discuss anything with her. When he goes to visit Lady Augusta in London, he keeps it from his wife. William’s promise to Lady Augusta, or rather the rather wobbly premise the author sets up that William can’t say anything to relieve his wife’s suspicions, even when he knows she’s upset, is what sets off the fatal tragedy of the novel. Captain Russel is all too willing to fan her paranoia, telling her that Lady Augusta and William had a daughter together.

Deceived by Russel, Lorina succumbs to a night of passion while her husband is away. She immediately regrets what she’s done. Like William’s mother before her, she calls aloud for her own death, and tumbles toward insanity. Completely unable to hide her anguish from Berrington upon his return, they have a final explosive conversation, excerpted in part below:

| “Dare you confess yourself an adulteress?” “I do confess it—Hear me—I am such: Foul as contagious itself! Wicked as those whom God has abandoned…Berrington, let my miseries be now ended by your hand…. My oath is broken—I have stained the marriage bed…My soul is sinking into perdition!” “Let it fall—Let it still fall!... Wretch! May an eternal night hang over your accursed head.” “It gathers!” cried Lorina, madly “…I see my mother’s lips trembling with a curse!... My deeds—” “Silence! Neither shall you speak, nor will I hear of them again…” A bar of iron, which was used for securing the window-shutters, was by his side. He snatched it up, and hurled it at his wife. It struck her head, and the bone yielded. Death was in the blow: She fell: No groan escaped her. |

Moonlight on the Norwegian Coast, Knud Baade

Moonlight on the Norwegian Coast, Knud Baade Lorina's death is not unlike a biblical stoning. Berrington raves for a while over his wife’s corpse, bids a frenzied goodbye to his little boy, then goes out to find Russel and…. And…

Um, actually I don’t know what happens next because there is one page (page 196) missing in the digitized copy and that one page is the page where Russel meets his death and Berrington also gets wounded. Anyway, on page 197, Berrington, bleeding from his wounds, raves some more, then flings himself into the ocean from a fisherman's rowboat. “She who bore me, could not keep herself in the ways of virtue—Prostitute!—She who was the mother of my child, ran into the broad path of vice, heated by licentiousness, and fearless of a cheated God—Adulteress--wicked adulteress!”

Triple tragedy, three corpses and one little orphaned boy.

William’s foster brother Robert Feller, now married, takes the orphaned child into his home, with the promise that when he’s old enough, Berrington’s army buddies will sponsor his education at some good school.

The author ends with an impassioned plea to the women of England to maintain their virtue and chastity, and for "Reason" to prevail, with a final sarcastic fling at “Philosophers,” by which he means the likes of William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft: “And they would shew the growth of intellect, the expansion of wisdom, the absurdities of worn-out prejudices!”

Fatal consequences of adultery

Fatal consequences of adultery The denouement of this story is, as I mentioned, extremely intense. However, Summersett doesn’t really start building up the tension until we’re well into the final volume. Possibly Berrington’s reaction was the stronger because of his shame over his own mother’s fall from virtue, which explains why Summersett opened the story the way he did. But the author made no use of this. William Berrington's illegitimacy was never an issue for him in his progress through life. We had no foreshadowing that we were heading for a tragedy, to explain why this kind and loving husband would flip into a deranged misogynist (I have barely quoted the things he said about Lorina before he killed himself).

Summersett could have likewise developed the character of Lorina to show that she was too easily swayed by others, or a little vain of her beauty, or something, to explain why she was vulnerable to Russel's blandishments. Austen, by comparison, gives us plenty of foreshadowing in Mansfield Park to warn us that Maria Bertram is headed for a fall.

Cultural norms: Co-ed public shaming for adultery in Japan

Cultural norms: Co-ed public shaming for adultery in Japan When it came out in 1804, The Worst of Stains received a single brief review in the Imperial Review. The reviewer did not deride the tale for being unrealistic or overblown. He wrote: “This is, alas! A romance of real life; it is an interesting, impressive, and truly moral tale.” No quibbles about whether the wages of sin were a tad excessive here.

As scholar Michael Giffin points out: “Literary criticism in the twentieth century has been highly secular in character, and thus has made it difficult for the academic critic to glimpse into the horizons of the ‘religious’ author and text…. The reader—whether secular or ‘religious’ –is ill-equipped or unable to recognize those subtexts.”

A reader of 1804 would have the religious knowledge—whether or not they had the actual religious convictions—which enabled them to pick up on the allusion to “Gabriel” and “Mary” in the book’s opening, to understand why William’s mother had to be declared insane to be buried in the churchyard, to understand that adultery was not merely a hurtful betrayal of one's spouse, but a statutory crime and a broken Commandment. A modern Western reader doesn’t necessarily have this knowledge, and most don’t share these beliefs, though they are certainly still extant in other cultures today.

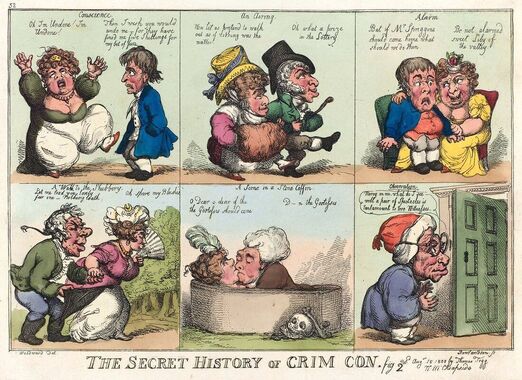

Finally, a reminder that although this book is as serious as the plague, and living a chaste and upright life was the prescribed social norm, people still committed adultery and people joked about adultery, known legally as "criminal conversation," or informally as "crim con." Lady Augusta has a bastard child and is punished with nothing more than an unhappy marriage, poor health and in the end, dying in exile from England. But she’s a toff, after all, and they are above the consequences of their actions in the way that ordinary folk aren’t, and perhaps a better writer would have made more of the contaminating influence of the aristocracy on the manners and morals of the lower orders. Below a cartoon by Thomas Rowlandson.

Scholar Steve Orman has provided a preface to The Worst of Stains in a 2014 re-issue by Valancourt books, which has also republished some other of Summersett’s forgotten novels. Of Henry Summersett himself, Orvan says, almost nothing is known. He does not rate a biography in the 1816 “Dictionary of Living Authors of Great Britain,” which lists only a few of his titles. He was a prolific author of novels and he wrote some poetry and a play. Most of his novels appear to feature a male protagonist.

Orban focusses on tracing the evident literary influences on the novel, for example, Othello. However, Desdemona did not cheat on Othello. William Berrington is not presented as a flawed human hastening toward a tragic downfall, as Othello is, but as a loving husband and father and an upright man whose wife fully acknowledged her guilt and said she deserved to die. The moral here is, “don’t have sex outside of marriage,” not “take a deep breath and count to ten.”

| Previous post: the hidden storyline in Jane Austen's Emma Next post: Time for something in a lighter vein | Giffin, Michael. "Jane Austen and the Economy of Salvation: Renewing the Drifting Church in Mansfield Park." Literature and Theology 14.1 (2000): 17-33. The Worst of Stains. Edited by Steve Orman. Valancourt Books, 2014. Steve Orman is an Associate Lecturer in the Department of English & Language Studies at Canterbury Christ Church University. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed