| This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws some occasional shade at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. |

Imperfect heroines -- Catherine Morland (Felicity Jones) in Northanger Abbey

Imperfect heroines -- Catherine Morland (Felicity Jones) in Northanger Abbey Of course, dramatic novels contained some comic leavening, usually provided by a garrulous servant who speaks with a regional accent. And comic authors still inveighed against the follies of the times. The anonymous author of I’ll Consider of It!! weighs in on a lot of topics, such as female education, boarding schools, animal cruelty, unhealthy corseting, and uncharitable people, but it is an essentially light-hearted novel. It was written in imitation of a fabulously successful book which had come out the year before, titled Thinks I to Myself. The narrator and characters keep repeating '"I'll consider of it!" on every other page, which gets tiresome. But the odd thing it, the narrator of I’ll Consider of It frequently interrupts himself to take a poke at Thinks I To Myself. I’ll get back to the strange relationship between TITM and ICoI later.

First, let’s meet our heroine, Charlotte Clarkson, who lives with her maternal grandfather, General Littlefame, and her widowed mother. The family are neither wealthy nor of high status, but the author arranged that Mrs. Clarkson fortuitously won five thousand pounds in the lottery, which is enough to get by with a single servant and to send Charlotte to a good boarding school. Mrs. Clarkson has high hopes for her lovely daughter…

Charlotte and her friend Valencia at boarding school. Bing AI image

Charlotte and her friend Valencia at boarding school. Bing AI image Here is part of the author’s first description of Charlotte. Charlotte sang well, but “she could not endure the fatigue and trouble of learning music, or the scientific, or rather flourishing part of that charming accomplishment, she always declared her inability when called upon to perform. She was very fond of working in the garden, digging, hoeing, riding on horseback, feeding poultry, and playing with dogs and cats; she was not fond or working at her needle; wristbanding of shirts was her aversion, and she hated the trouble of writing a letter.”

Janeites will, I think, be reminded of another heroine who was created before 1800 but wasn’t published until 1818. At any rate, Charlotte is not interested in becoming an author.

Charlotte is a good-hearted, good-natured girl, who is quite aware of her feminine appeal. I think the author gives a more realistic picture of a young lady than you’ll find in the melodramas. For example, instead of having only one true love, Charlotte has three suitors—the young and handsome Mr. Dorimon, who is wealthy but avaricious, the older but handsome Major Farringdon, proud of his family tree, and Henry Denbigh, an open-hearted young man who is the heir to his father’s huge East Indian fortune. When she thinks Mr. Dorimon has injured himself in a fall from his horse, she tries her best to faint, as a sentimental heroine should. When Major Farringdon calls in the morning while her hair is still in curl papers, she races upstairs to her bedroom.

Man Milliner (note the yardstick): 'Indeed Mr Fribble... your yard is too short by an Inch.'

Man Milliner (note the yardstick): 'Indeed Mr Fribble... your yard is too short by an Inch.' Heroes and heroines in comic novels have impediments keeping them apart, just as they do in melodramas, it’s just everything is handled with a humorous tone. Charlotte and Henry (for Henry is our hero) meet accidentally on the street when he pulls her out of the way of a runaway carriage, but they don’t know each other’s names, and he has to go off to Madeira to retrieve some of his father’s papers. She meanwhile, imagines herself in love with Mr. Dorimon but also is attracted to Major Farringdon, and he to her, but he can’t overcome the fact that her father was a lowly tradesman, a "man milliner," no less. Mr. Dorimon’s parents also discourage his courtship of Charlotte because she has no dowry, but that changes when General Littlefame suddenly inherits thirty thousand pounds, (as one does).

Although Major Farringdon is faulted for his vanity and vacillation, he is portrayed as an honorable man and he appears to be the mouthpiece for the author’s opinions. For example, here he is talking about the faults of modern women and how he lost his first wife: “they are utter strangers to the domestic duties, and the rearing of their own offspring, when they come to be mothers, which, however, the cold steel of their long busked stays, which many do not throw off when even in a state of pregnancy, bids fair to deprive them of the sacred title of a parent, and to depopulate our country more than an eight years disastrous war. Such,” added he, with a sigh, “was the sad and fatal result of Mrs. Farringdon’s inordinate love of modish attire; her only child was destroyed before it ever saw the light, and continual spasm and cramps terminated in an inward complaint in the chest, which baffled all the skill of the physicians, and soon sent the victim of fashion to the tomb.”

Lady con artist tries to enchant the miserly Mr. Caseknife, but fails. Bing AI image

Lady con artist tries to enchant the miserly Mr. Caseknife, but fails. Bing AI image We also have two con artists, a brother and sister who spent most of their lives in India, the son and daughter of "an English drum-major" and his wife. They take on half-a-dozen names in the novel but I’ll call them the Jenkinses. There's a fun episode where they try to pretend a letter revealing their evil plans is actually part of a manuscript for a novel. They pretend they've been offered one hundred guineas for the manuscript, a sly inside publishing joke at a time when some publishers were paying as little as ten pounds to aspiring authors. Mr. Jenkins "was of that very dark complexion, as served to engender doubts in [his father's] breast, whether or no he was not the unlawful offspring of some man of colour; but, as some men of title, high birth and fashion, very quietly put their branching antlers in their pockets, so the poor drum-major thought it best to do the same.” The narrator then goes on to say things about mixed-race unions that I won't repeat here but it might be of interest to researchers; it's at Volume 2, page 53.

That said, Jenkins' racial heritage is not used to explain his criminal propensities, rather the opposite; the narrator suggests it is contact with Western culture that has corrupted him. Jenkins' multiracial identity is useful for the plot because it enables him to pretend he is a famous dead-but-reincarnated “brahmin,” or Indian mystic--because, and this might truly seem bizarre in an English novel published in 1812--another theme of the book is reincarnation. The author uses Hinduism and reincarnation the same way a gothic novelist might use ghosts: “Jenkins, by some chemical preparation, made the lights burn dim, and played, for a short time, a faint phosphoric blaze over his own head; then after having duped the enthusiastic Henry [Denbigh] of his watch and valuable pocket-book, he stole softly out, slipped off his Brahmin’s disguise in one of the passages, walked boldly into street, and walked quietly home.”

Things kick into high gear in the third volume, when the author adds some new characters who all converge on London for various reasons. Charlotte realizes she doesn't want to marry Mr. Dorimon when he is cruelly dismissive to a poor old English ex-pat looking for a job as a clerk. I enjoyed the scene in which she firmly breaks up with him, with his parents and her mother and grandfather present. Soon after, she is coincidentally reunited with Henry Denbigh and realizes she’s found her soul mate: “The mind of the amiable Charlotte, relieved of the leaden weight which had oppressed it… and full of the remembrance of Henry’s fine person, his elegance of manners, and the benevolent and generous disposition he had evinced sunk into a calm and sweet repose, as she prest her downy pillow, where visions of happiness flitted before her fancy, and bound her sleeping senses in rosy fetters.”

What she doesn't know, but learns later, is that Henry is the source of the thirty thousand pounds that lifted her from being a nobody to an heiress, nor did he know about her existence generously shared his inheritance with General Littlefame. Well, in this book the coincidences are satisfying. We learn the poor old ex-pat’s backstory and his unfortunate ties to the nefarious doings of the Jenkinses in India. All the pigeons come home to roost at a gambling den in London, when Henry Denbigh catches Jenkins in the act of fleecing one of his friends. The victims get restitution and the Jenkinses are sent to New South Wales.

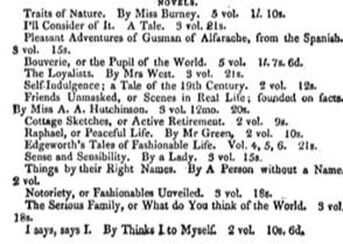

| Authorial rivalry? It's one thing to write your book in imitation of a best-seller. Hannah More’s Coelebs in Search of a Wife spawned a host of imitations. Gothic novelists were basically copying Anne Radcliffe. Then there were the “season” novels I’ve discussed elsewhere. But here, an author has imitated the discursive style and lighthearted tone of Thinks I to Myself with the similarly titled I’ll Consider of It, but then repeatedly takes a poke at the book he is imitating! I’ll Consider of It got no reviews when it came out, which is unfortunate, as a reviewer might have shed some light on the author's sly allusions to famous people and nobility, for example, the Countess of C____ and O____, and a review would have mentioned this author’s strange fixation on the novel he is trying to imitate. | Sense and Sensibility, I'll Consider of it, and Edward Nares' second novel, I Says, Says I, all listed in the Edinburgh Review, Nov 1812. As well, Traits of Nature by Fanny Burney's sister, advertised as "Miss Burney." A reminder that these forgotten best-sellers were contemporary with the "all perfect Austen." |

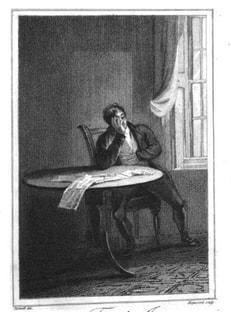

Thinks I To Myself frontispiece, 7th edition

Thinks I To Myself frontispiece, 7th edition The author of TITM is Edward Nares. Thinks I To Myself got lukewarm reviews at best but it went through six editions in less than a year, and a seventh edition with a different publisher, which suggests Nares had a break with his first publisher, perhaps a disagreement over money matters. The 7th edition included a frontispiece of the author, hiding his face. The narrator of ICoI keeps referring to the number of editions of TITM. He seems to be hinting at some inside knowledge about the reasons behind the success of Thinks I To Myself.

This strange attack on one novel by another novelist has led some people to suggest that the same author wrote both books and it's just a running gag. Possibly, but TITM and the follow-up novel, I Says, Says I, are written in the first person. I’ll Consider of It I'll A tale, in which 'Thinks I to myself' is partially considered, is written in the third person and is published by a different publisher. And although ICoI is written in imitation, it still feels like a different voice, at least to me.

Nares has an interesting backstory. He was an Oxford vicar who became involved in private theatricals at the stately English estate of Blenheim. In 1797 he eloped with a Lady Catherine Spencer. Sadly, she died five years later. The story is told in A Spencer Love Affair (2013) by Allan Ledger.

I previously mentioned TITM in an earlier post about female education, a theme it shares with ICoI. Nares also wrote non-fiction and religious works.

Previous post: A melodrama about adultery Next post: Ellen, the lucky heroine--or is she?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed