| Clutching My Pearls is mostly about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. The opinions are mine, but I don't claim originality. Click here for the first in the series. For more about other female writers of Austen's time, click the "Authoresses" tag in the Categories list to the right. |

resemblance to another famous novel

Bing AI generated image

Bing AI generated image The drama of the story takes place after the wedding. Ellen doesn't know that her husband is an earl until after the honeymoon; she thinks he’s simply a wealthy gentleman. Then Pinchard adds in gothic elements such as travelogue sequences, sleepwalking, and a murder mystery.

Ellen knows only that her husband had a first wife who died abroad, and every now and then he gets moody, breaks out in exclamations and abruptly leaves the room. Has she married a murderer or something? No, it couldn’t be. She has complete confidence in him, despite the mystery he refuses to unveil...

In Volume 2, Ellen takes up her new life as Lady St. Aubyn. Like all good heroines, Ellen prefers the innocent pleasures of the country to the dissipation of the city. We meet the neighbors, an assortment of side characters useful for displaying laughable or admirable character traits, even if they don't advance the plot. There’s a “mutton-dressed-as-lamb” old maid, a neighbor who likes to complain a lot, and a beautiful young girl, pious and learned, who is dying of consumption. She studies Greek and hopes to learn Hebrew, but she is not, heaven forbid, pedantic about it.

More adventures await in London, where Ellen goes to a masquerade ball where--absolutely nothing untoward happens! Talk about a plot twist. Ellen's good sense and sweet nature win over Lord St. Aubyn's proud and unbending aunt, who gets “the better of the shock he gave my pride, call it prejudice if you will, by marrying you."

| When they go to the opera, Constantine starts acting strange again because the opera they are watching, Artaserse (1730), features a man accused of murder who cannot prove his innocence. As well, in the lobby, Ellen bumps into her old village suitor Charles Ross, who assumes that she’s a painted doxy seduced by Mr. Mordaunt (he’s been to sea and hadn’t heard she was married). Luckily, they clear up the obvious misunderstanding in no time. Just kidding. No, they don’t. Ellen faints, Charles insults Constantine, and they arrange to fight a duel, and then Constantine assumes that Ellen is carrying a torch for Charles. Things get pretty serious before Constantine stops raving long enough to listen to reason. The couple are reconciled and go back at their country estate to await the birth of their first child. Constantine’s ward Edmund de Montfort shows up, which forces Constantine to finally explain to Ellen why he keeps smiting his forehood and rushing out of the room. Edmund is the younger brother of Constantine's first wife, who died under mysterious circumstances in Spain. In a cave with a gunshot to the back of her head, in fact. With his dueling pistol left at the scene of the crime. All the circumstantial evidence points to him, when really (he swears) Rosolia was murdered by her lover, who hasn’t been seen since. |

|

Bejarano. A Bolero dancer, 1842

Bejarano. A Bolero dancer, 1842 As an aside, I think the author chose to make Rosolia and her brother Edmund half-Spanish to account for their tempestuous natures, and it allows her to place the melodramatic section of her plot in the exotic setting of Spain.

Edmund, no less than Constantine, is haunted by the death of Rosolia. He prowls around sleepwalking. exclaiming in broken phrases about his lost sister. We learn in the backstory that Rosolia neglected her infant son, who died. She ignored her husband, flirted, danced suggestively in public, and started passing on her jewels and money to her lover in preparation for running away with him. If that's not bad enough, we are told she took no pleasure in the sublimities of the Spanish landscape: the “charming and picturesque views…. Alas! The heart of Rosolia was shut to them all.”

Edmund has now reached his legal majority (in his case, the age of 24), which is when he promised to either absolve his brother-in-law of murder, or to actively prosecute him as a murderer.

So how do we get out of this situation? How does Constantine clear his name and solve the mystery?

The author takes our hero and heroine back to Wales so Ellen can visit her father and show off her baby boy. For the first time, the narrator mentions that this Welsh village just happens to be near the sea. And there just happens to be a violent storm. And there just happens to be a shipwreck, and among the survivors rescued by Constantine and the men of the village, we have everybody necessary for wrapping up the plot—young Charles Ross is swept ashore to his home village, along with a mysterious “Algerine,” who turns out to be the fugitive De Sylva, Rosolia’s lover. Plus, also bobbing in to shore is a Catholic priest who can act as an impartial witness to take down De Sylva's confession in his native French, to send to Edmund. (De Sylva claims he tripped and the gun went off by accident, so he fled with the jewels.)

Well, the great Charles Dickens was not above using a similar amazing coincidence in David Copperfield. And the shipwreck ties in with the opera Artaserse, because Arbace compares his situation to being shipwrecked.

De Sylva dies after declaring that Constantine is completely innocent. Constantine and Ellen live happily ever after.

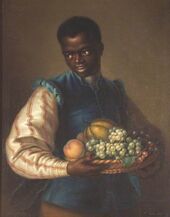

Status symbol and fashion statement

Status symbol and fashion statement Pinchard likes to drop in allusions to literature. She occasionally commits poetry and she starts her chapter headings with quotations from the poets and from Shakespeare. These quotes, like the opera, tie Pinchard's tale to themes in literature and poetry, such as jealousy.

In her spare time, the heroine does charitable deeds for the poor.

There’s a passing mention of “two black servants” in the lavishly decorated home of a lounging society woman who is fond of turbans and incense and revealing attire. They are exotic displays of her wealth and taste.

Slavery comes into the conclusion of the novel when we discover where the villain who seduced the first Lady St. Aubyn has been hiding all this time: he was kidnapped by Algerine pirates and enslaved in North Africa. The enslavement of Britons by Algerine pirates is simply a plot convenience here, a fact of life. It's another marker of the villainy of the villain that he willingly converted to Islam when adopted by a Muslim merchant during his captivity. “Robber! Murderer! Vile apostate from thy God!” exclaims Constantine. He probably doesn't appreciate the sublimity of nature, either.

Mrs. Danvers and the second Mrs. De Winter

Mrs. Danvers and the second Mrs. De Winter ...which is the academic term for resemblances/influences between works of fiction, you can't miss the similarities between this novel and Rebecca.

As it happens, when Daphne Du Maurier published her best-seller in 1938, she was accused of plagiarizing from a Brazilian novelist, Carolina Nabuco, as well as from the author of a novel called Blind Windows. This synopsis makes it clear that there's no significant similarity between Blind Windows and Rebecca--only a big house and an older man marrying a younger girl. The Brazilian novel is eerily comparable to Rebecca, according to a Nov 16, 1941 New York Times article, except that the denouement is not so dramatic.

There are many similarities between Rebecca and Mystery and Confidence (villainous and unfaithful first wife dies mysteriously, older man haunted by the past marries naïve girl, big country house), yet there are many differences as well. Ellen is amazed but not completely intimidated by her elevation in society. Her husband's housekeeper, Mrs. Bayfield, is fiercely loyal to him, not to his dead wife. Constantine is secretive and moody but he's not as deranged as Max De Winter. But... apart from all the other similarities, in both books, the mystery is resolved because of a shipwreck! I mean, come on! Did Du Maurier read Pinchard? You have to wonder.

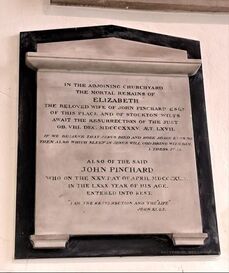

Elizabeth Sibthorpe Pinchard (1768-1835) married a lawyer and according to a public genealogy website, had eight children. A memorial plaque to Elizabeth and her husband was placed in St. Mary Magdalene Church in Taunton. Just as with Jane Austen, this plaque does not mention Elizabeth Pinchard's identity as an author.

Mystery and Confidence received a favourable review from the Critical Review: "This tale is naturally told, and it also possesses the advantage of being disencumbered from episodes, under plots, and counterplots, which, of late years, chilling thought! seems to have become necessary to eke out five or six volumes of novel or romance. It contains one clear unbroken chain of events, connected by a moral, interesting and unaffected narrative.”

I found Mystery and Confidence to be a quick read with a number of likeable characters. The heroine is "a picture of perfection" but she's not obnoxious. There are some nice little vignettes of gossipy village life. The backstory of Rosolia is Gothically entertaining and the travelogue sections make me want to visit Wales.

Pinchard wrote several other novels as well as works for young people, such as the best-seller The Blind Child (1791).

This 1814 novel provides many examples of incidents and techniques which, if you had only read Jane Austen, you might assume were unique to Austen: The hero meets the heroine when he helps her get home in a thunderstorm when she slips descending a hill, he uses his influence to raise Charles Ross from midshipman to lieutenant, he's a mentor as well as a lover, the proud aunt deplores the marriage and is rude to Ellen (at first), the heroine goes to her room to compose herself because she is too happy to appear in company, and the narrator skips over the actual proposal scene.

Of course there are many things in Pinchard that we don't find in Austen, such as masquerade balls, white slavery and anti-Catholicism. And when it comes to giving the reader clues about a mystery, Austen reached a level of sophistication in Emma far beyond what we find in Mystery and Confidence.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed